This article unpacks the complexities of international taxation in the digital era. It discusses the challenges traditional tax models face with online businesses and the rise of unilateral Digital Service Taxes by developing nations. It highlights the OECD’s Two-Pillar approach, with a focus on Pillar 1 and its core component, Amount A. Through real-world examples, it navigates the intricacies and controversies surrounding global tax policy developments. This series was written by Samvedh, Kartheek, Dhanush, and Aditya from the CTL team.

Introduction

The imperial nature of the current DTAA regime was explored in the previous article, referencing both the structure of the tax treaties themselves as well as the concomitant institutional set-ups. The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) model dominates the landscape of international tax through its residency-based regime that prevents a country from taxing an entity without a ‘Permanent Establishment’. In a digital economy, the inequitable effects of this regime are amplified when business can be effectively conducted without any tangible presence in Third World countries.

This article in the series will examine how developing countries have retaliated against the Permanent Establishment concept through the imposition of E-Commerce taxes on these digital entities that operate across borders. The previous article looked into the imperial nature of the Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAAs) and the broader international tax regime, which perpetuate the colonial practice of vesting the right to tax revenue from developing countries in developed nations. The pervious article higlights scholarship across the world which argues that the current tax regime lacks legitimacy, leading to inequitable distribution of tax revenue and exacerbating global inequalities, necessitating a more inclusive and equitable approach.

The focus of this article in particular is to provide context for the necessity and consequent development of Pillar 1. It will explore its mechanisms and concepts, subsequent to which it will examine its effects on the dynamics between the Global North and Global South.

The Permanent Establishment Conundrum

As highlighted in the first part of this series, the Organisation of Economic Development defines a Permanent Establishment (‘PE’) as “a fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on”.[1] A PE is therefore a a taxable presence a company has outside its country of original residence. By establishing a physical presence and carrying out business operations in a nation outside its residence country, the company acquires a form that makes its revenue taxable in the other country.

A PE has traditionally been the sole method through which cross-border taxation takes place. For a contracting State A (source of income) to be able to tax the business profits of an enterprise belonging to the other contracting State B (residency of the company), the enterprise must have a permanent establishment within the territory of State A, absent which it will have no right to levy any tax.

Across DTAAs, three forms of PEs currently exist: ‘Fixed Place of Business PE’, ‘Agency PE’, and ‘Construction, Installation and Supervisory PE’.[2] A common link between these forms is that the company must establish a physical presence in the source country for a tax liability to arise under its laws. With the advent of the digital age, where corporations leverage the Internet and information technology to penetrate borders without a physical presence, the OECD itself has admitted that such ‘brick and mortar’ rules challenges the existing profit allocation and nexus rules to distribute taxing rights on income generated from cross-border activities in a way that is acceptable to all countries[3].

The importance that a PE holds to a source country (most frequently a developing nation) in the current taxation regime can be seen in how it underlies the OECD model itself. For instance, Article 10(4) of the Model Taxation Treaty 2017, concerning dividends, provides that the source country shall tax all dividends of a foreign entity if such dividends are paid in connection with the PE within the territory, or are otherwise connected to it.[4] The same logic extends to the receipt of interest payments, royalties, capital gains, and other forms of payment attributable in any manner to the PE in that country.

However, online business models undercut the ability of source nations to tax income through the use of Permanent Establishments. In these situations, the transactions are intangible in nature, which makes it impossible to determine if there is a PE. The commentary to the articles of the OECD model[5] recognises this problem as well by acknowledging that in case of online businesses, no location in a source country where it does not reside, can constitute a place of business since there are no premises, machinery, or equipment (save in a few cases), any of which are necessary elements to constitute a PE under Article 5.

Since Internet Service Providers (‘ISPs’) ordinarily have servers in the country they operate in, it may be argued that these ISPs are agents who facilitate the digital operations of the enterprise are a form of Agency PE, thereby bringing the non-resident company within the taxable jurisdiction of the source country. However, the aforementioned commentary specifies that ISPs will not constitute an agent of the enterprises to which the websites belong since they wield no authority to conclude contracts on behalf of and in the name of these enterprises. They have also made it clear that the website through which an enterprise carries on its business is not in itself a “person” as defined in Article 3(5) and cannot apply to deem that there exists a PE because the website can be an agent of the enterprise to constitute Agency PE.[6]

In summary, if a resident belonging to the ‘source’ State completes a purchase on the website owned by a resident of the ‘residence’ state, there is no possibility of the former collecting any taxes, as there is no PE to which such income is attributable.

The Digital PE Problem

The problem with the aforementioned position is that developed countries, which house most digital giants conducting business online, can collect taxes on worldwide income earned by such companies. At the same time, however, a source country cannot tax a digitally operating non-resident company that generates income from its territories since there is no PE. Many developing and even developed nations in disagreement with the model imposed levies on digital services in contravention of the residency-based OECD model. E-commerce transactions by a non-resident enterprise, operating virtually in a market jurisdiction have been taxed by such market jurisdictions, regardless of whether it hosts a PE. Such levies are commonly referred to as Digital Service Taxes (DST)

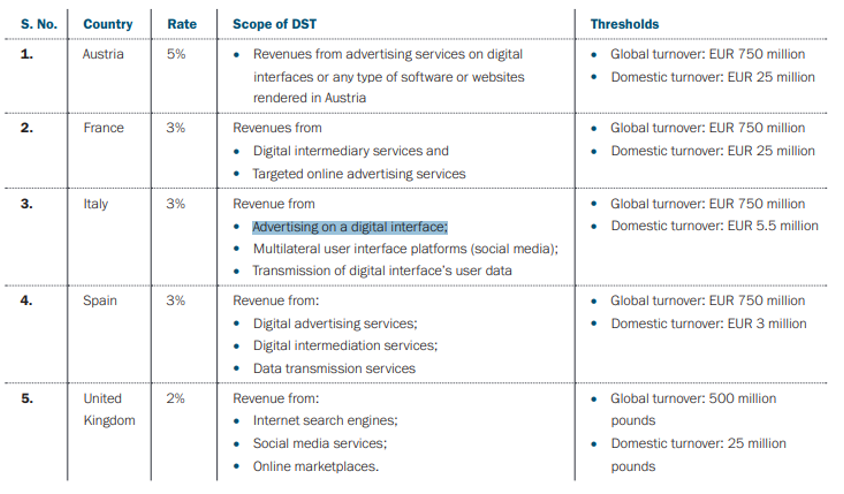

The following chart demonstrates a few examples of such unilateral DSTs imposed by countries:

In India, there are two DSTs currently levied, termed as an ‘equalisation levy’.

The first is a 6% tax imposed on non-resident entities, on revenues earned by them from online advertising services, introduced vide the Finance Act, 2016.[7] The second levy was introduced vide the Finance Act, 2020, imposing a 2% tax on revenues generated from e-commerce operations in India, earned by a non-resident entity.[8]

The common thread amongst all these countries and more is the unilateral imposition of a digital tax in contravention of Article 7 of the OECD Model Tax treaty. The leading rationale behind such taxes is that any income earned by a corporation in the source country should not be able to unjustly avoid taxes by hiding behind the outdated PE concept in the inflexible OECD model, merely because they operate digitally.[9]

The European Union, for instance, argues that it is unfair to exempt companies earning online revenue from taxation in the source jurisdiction as per the OECD-based DTAA merely because there is no PE in the source country.[10] Since the income the non-resident company earns through digital operations is attributable to the source country, the EU argues that the source country must be able to levy tax on such a non-resident company despite the absence of a PE.[11]

Similarly, India’s pursuit of taxing profits derived virtually has been assisted by the judiciary, whose interpretations have diluted the PE concept. In the case of Galileo International and Amadeus Global Travel v. Deputy Commissioner Income Tax,[12] the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal at Delhi unilaterally digressed from the universal understanding of a PE, stating that if a company is deriving revenues and profits through a virtual presence, then the company’s virtual presence constitutes a “virtual PE”, making such companies liable to pay tax in India with respect to the profits earned therein. ((However, such a position has been reversed in subsequent decisions, such as Clifford Chance v/s ACIT)

The unilateral actions of these countries directly contravene the provisions of the OECD Model DTAA. Engaging in domestic rulemaking in contravention of international treaties in this context risks rendering the OECD Model obsolete, and, more importantly, would have consequences on multilateral relations between countries who have consented to using this model. To ensure the goals of development through taxation revenue, opposing countries risk effacing PE-driven taxation.

The primary champion against such unilateral levies is the United States, which contends that such impositions are prejudicial to the interests of American companies that digitally operate in foreign countries without any PE. USA further argues that the imposition of such digital taxes is in contravention of settled international law. In an investigatory report on India’s digital services tax, the US objected to the levy on non-resident entities, arguing that the tax is discriminatory as it applies only to non-Indian companies. The report additionally states that the imposition of such a tax is an unwarranted extraterritorial application of domestic law, and taxing revenue instead of income contravenes international tax principles.[13]

The Two-Pillar Solution

To resolve this conundrum, the OECD’s inclusive framework on Base Erosion Profit Shifting (BEPS) has formulated a Two-Pillar approach (dubbed as BEPS 2.0) that would help address concerns regarding tax avoidance, provide for a transparent tax environment, and ensure consistency in international tax rules.[14] The Two-Pillar plan addresses the challenges of digitisation in international trade and commerce by reforming international taxation to ensure that multinational enterprises pay their fair share of tax wherever they operate.

In this second half of the third part of this series, we shall look into Amount A specifically, after gaining a broad understanding of what Pillar 1 entails for countries signing up to it.

Pillar 1

Pillar 1 consists of three components:[15]

- New taxing rights for source jurisdictions, where a share of the residual profit of some of the most profitable Multinational Entities (MNEs) groups is allotted to such jurisdictions, termed ‘Amount A’ within the Pillar 1 framework.

- Amount B is the second component of Pillar 1, which essentially simplifies the existing transfer pricing rules by providing a fixed return for certain baseline marketing and distribution activities physically in a market jurisdiction in line with the Arm’s Length principle.

- Improving tax certainty through effective and functional dispute prevention and resolution mechanisms, which are binding and mandatory on signatory countries.

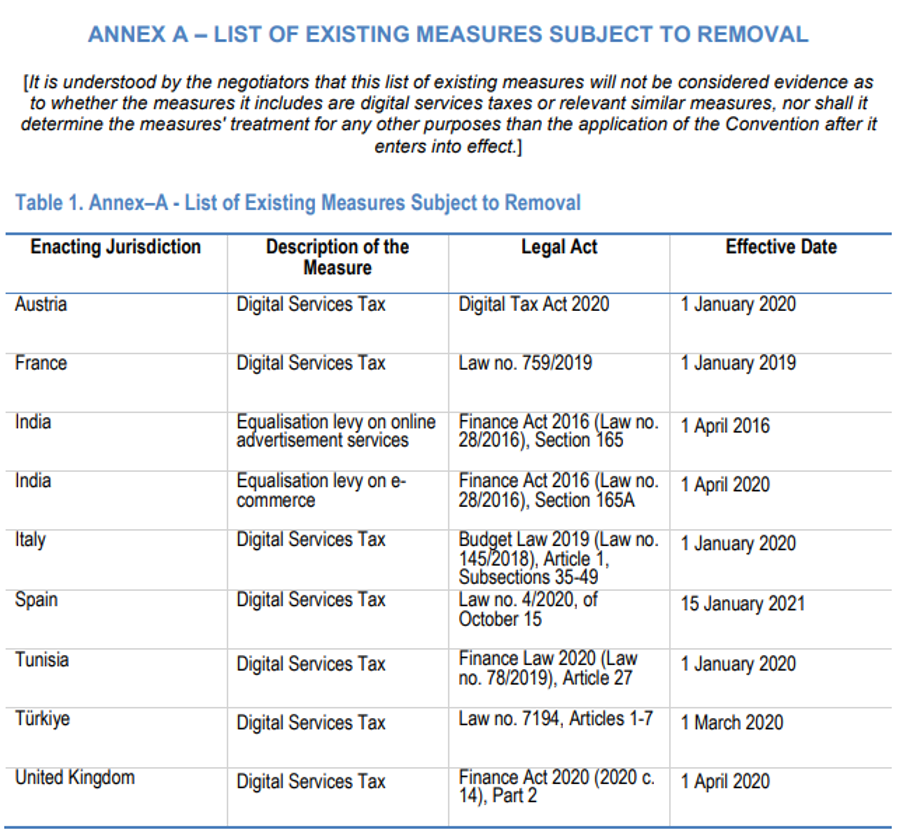

A prerequisite for the adoption of Pillar 1, or more specifically Amount A, is that countries must retire their DSTs.[16] In response, most countries have agreed to abandon their DSTs, contingent on the implementation of Pillar 1. Given that the discussion so far has been in the context of DSTs, it is pertinent to examine the Amount A component in further detail

Amount A

The OECD has recently released the Multilateral Convention (MLC) to implement Amount A of Pillar One. Given the contemporaneity of the issue, it is relevant to examine as to what effects it has on the global north-south divide.

The context behind the introduction of Amount A is the entire DST conundrum we have discussed above. The USA, viewing DSTs as a discriminatory trade measure, has imposed trade sanctions that have adopted DSTs, viewing them as discriminatory measures against USA’s tech giants[17].

This led to a looming threat of a trade war, which set the context to Pillar 1 negotiations, leading to the amount A component. While USA and other jurisdictions housing high revenue companies have to give up taxing rights over marginal profit amounts, the quid pro quo, specifically for the USA, is that taxing rights over Amount A profits will not be allocated to source jurisdictions if there is a concurrently operating DST levy.

Amount A shares taxation rights over residual profits of MNEs with the source country, irrespective of whether such enterprises have a physical presence in the form of a PE.

The first step is to identify as to whether a particular MNE falls within the scope of Amount A. The following criterions are used to determine this.

- Whether the MNE has a global turnover of 20 billion Euros or more

- A profit margin of 10% or more (Calculated as profit before taxes)

The second step will be to calculate the taxing rights which are to be reallocated, which essentially will be up to 25% of the profits over and above the 10% profitability threshold to the source country.[18] Profitability of up to 10% is viewed as routine profits and since the aim of Amount A is reallocate taxing rights of excess profits generated by a high revenue MNE, profits up to 10% margin are not reallocated to source jurisdictions[19].

To illustrate how Amount A is calculated, let us assume that a company generates 20 billion euros in revenue and profits worth 10 billion euros, bringing it under the scope of the pillar as it meets the >10% threshold. The next step would be to calculate 25% of the profits of the amount above 10% of profits. Since the profits in this case are 50% of the total revenue, the taxable Amount A would be the amount of profits over 10%, i.e., 40% of the total revenue. Since the latter amount would be 8 billion euros, the actual taxable amount would be 25% of 8 billion, or 2 billion euros. This final amount will be reallocated to the source countries where the MNE has operated.

If an MNE does not meet this threshold, but one of its segments on a standalone basis does so, then such segment’s Amount A will be calculated, which will consequently be taxable in the source jurisdiction.[20]

Argentina’s Economy Minister, Martin Guzman, has said that adoption of Amount A and Pilar was a choice between a bad deal or worse, no deal at all[21]. India was arguing for a threshold of 1 billion Euros as against the 20 billion Euros currently operational, which would have brought nearly 5000 companies within the scope of Amount A, instead of the current number of a hundred companies[22]. India has also pitched that taxing rights over at least 30% of profits instead of the current 25% should be reallocated to source jurisdictions.[23]

The African countries, represented by the African Tax Administrative Forum (ATAF), claim that Pillar 1 does not meet the aspirations of African countries[24]. The first point they have raised is that the share of profit margin (which was then proposed to be 20% instead of 25%), over and above the 10% of profit amounts, is too little an amount for reallocation purposes. Secondly, the routine profits of MNEs covered under Amount A would still be subject to taxation in the source jurisdiction if there is a physical presence of the MNE as per existing DTAA norms. But the same routine profits will be excluded from taxation in case of digital companies if they have no physical nexus in the source jurisdiction, allowing source jurisdictions to levy taxes only on 25% of the profits over and above the 10% profit amount. This, as per ATAF, cannot be seen as an equitable or desirable outcome of Amount A reallocation rights.

Additionally, a lot of companies based out of the Global North which meet the revenue threshold would be able to escape the application of Pillar 1 by demonstrating profitability below 10%[25]. For instance, Amazon Inc., the largest e-commerce corporation in terms of market capitalisation and revenue, is a loss making entity.[26] The withdrawal of digital levies and the implementation of Pillar 1 would entail that e-commerce operators such as Amazon would not be liable to pay any tax to source jurisdictions (assuming that they do not have a PE in such jurisdiction), even on the income earned from such source jurisdictions.

OECD, however, has countered such concerns using the principled argument that upto 10% of profits represent a normal level of profitability, which should be subject to tax in the parent jurisdiction or as per existing PE rules. A profitability over 10% indicates that the MNE is a highly profitable group, which makes it justifiable for its taxing rights to be reallocated, despite a lack of nexus under established PE rules.

Additionally, as per OECD, Amount A ensures for a fairer distribution of taxing rights among countries with respect to large MNE’s. While Amount A was initially touted to be applicable only against Internet giants, it’s scope was expanded to include all companies with the exception of extractives and regulated financial service[27]s. The Amount A policy represents an amicable compromise between American interests of protecting technology companies, with the necessity of developing countries to tax profits attributable to their jurisdiction.

As per the expectation of the OECD, nearly 200 billion dollars’ worth of profits will be reallocated to market/source jurisdictions using the Pillar 1 approach.[28] The quid pro quo for the developed countries is that there will be no more unilaterally imposed DSTs upon Pillar 1 implementation, with some progress already having happened in this context. Austria, France, Italy, Spain and the UK, among others, have agreed to revoke the digital taxes that they had levied once Pillar 1 measures come into force.[29] Even developing countries stand to gain tax revenues in the long term, with limited administration costs

A primary point of opposition against Amount A in the earlier stages of its discussions was that the administrative costs of handling Amount A reallocations might not justify the tax revenues from reallocation, for developing countries. But, as per the MLC, the administrative burden of handling all administration and filing relating to Amount A rests with the jurisdiction where the Ultimate Parent entity (UPE) resides, which will be designated the Lead Tax Administrator (LTA) (unless another entity of the MNE in another jurisdiction is designated for the purpose). The UPE or the designated entity has the responsibility to transmit the payable tax amounts to the respective authorities in the eligible jurisdictions.

Another primary point of focus in the context of our discussion is that parties to the Amount A MLC have to withdraw their DSTs and relevant similar measures (RSMs) before they are allocated any taxing rights under the Amount A framework, as per Article 38 of the MLC. Article 39 of the MLC, which looks at three criteria to determine whether a measure is a ‘DST or a relevant similar measures’, namely –

- If the tax is applied by reference to market based criteria (for instance, by the location of the customers and users)

- If it, dejure or defacto, ring fenced to non-resident or foreign owned businesses, and;

- It is outside the scope of tax treaties.

Annexure A of the MLC provides an indicative list of what constitutes a DST and relevant similar measures. Non-inclusion of a measure in the list, however, is not evidence as to whether or not a measure is a DST or a RSM as defined by the MLC

A review as to whether a measure constitutes a DST and RSM, will be done by the Conference of Parties (CoP), established as per Article 47 of the MLC. The review process will be conducted by the CoP as per the procedure laid down in Annexure H of the MLC.

As per Article 40 the MLC, even certain measures and tests, such as the Significant Economic Presence test, which do not require physical presence to establish nexus, are included in DTAA’s, they will not be allowed to apply on MNEs falling within the scope of Amount A. Even though such measures do not constitute a DST and RSM by virtue of being mentioned in a DTAA, it is believed that such measures defeat the purposes of Amount A and might lead to a situation of double taxation and therefore, such measures must not apply to MNEs within the scope of Amount A.

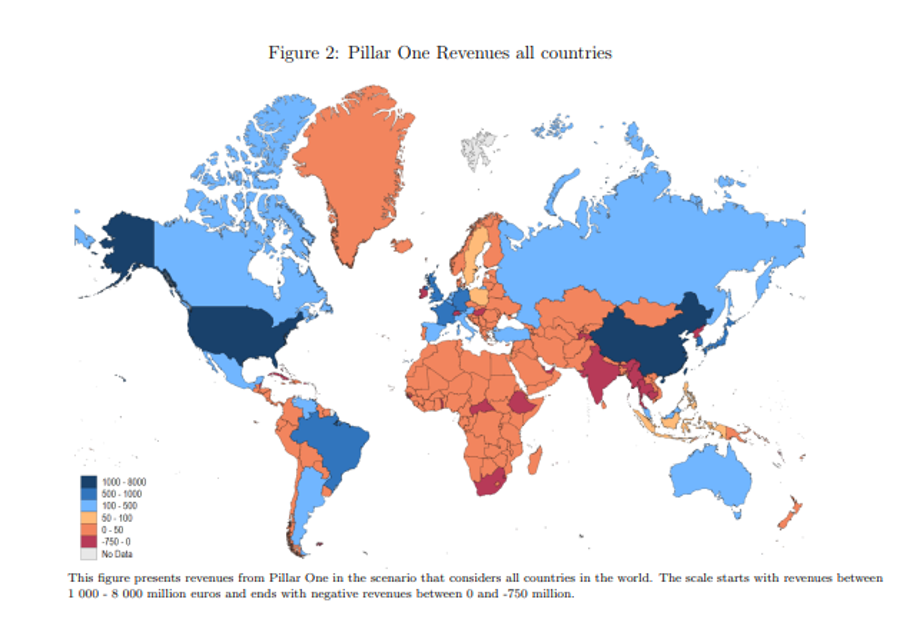

The quid pro quo is apparent and clear to the developing countries – increased tax revenues. But the fact remains that the Global North stands to gain more in terms of absolute revenues. When examining all the entities covered by Pillar 1, a study by the EU Tax Observatory found that Pillar 1 implementation stands to benefit the Global North in absolute terms.[30] With the exception of China, the Global South countries make negligible gains in terms of taxable amounts,. Most of Africa and Asia stand to gain a nominal increase in tax revenues[31]. In contrast, most developed countries, primarily in North America and West Europe, stand to gain significant tax revenue.

This is further augmented by an International Monetary Fund (IMF)report, which studied the consequences of Pillar 1 implementation, has found that many developing countries may lose revenue under Pillar one[32]. For instance, Vietnam stands to lose about 0.11% of GDP in revenue, due to the profit reallocation of Japanese MNEs. Even with respect to other developed countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and India stand to lose a nominal 0.01% of GDP in revenue. In contrast, high-income countries such as Korea, Australia and Japan, and large markets such as China, stand to gain significant tax revenues under Amount A.

The mandatory withdrawal of DSTs has been a point of contention for many developing and underdeveloped countries. For instance, Kenya was holding out against signing up to Amount A implementation until recently. Kenya had initially critiqued the Two pillar solution as being unfair to developing countries[33]. Under the 20 billion euro threshold, only 11 MNE’s would be required to pay any taxes in Kenya, as opposed to 89 MNEs which are currently being taxed under Kenya’s 1.5% DST.[34] Ultimately, Kenya did join the two-pillar solution, as its non-participation proved a roadblock in its negotiations for a free trade agreement with the United States.[35]

Further, the United Nations (UN) in a letter to the OECD had outlined how the current proposal of implementation of pillar allocates only a small portion of the residual profits of the hundred largest multinational companies[36]. The letter further states that the proposed thresholds of Pillar 1 of the global tax reform might exclude companies that have a significant economic presence in developing countries, potentially impacting their ability to collect tax revenues effectively[37].

The UN has also expressed concern that reallocation of taxation rights under Amount A might not be of much benefit to non OECD countries and can also reduce tax revenues for lower-income countries[38]. It suggested that the apportionment of revenue to source countries for taxation purposes must take into account employment and capital deployed, alongside revenues[39].

Additionally, concerns were also raised about the lack of transparency with regard to the economic rationale and the empirical assumptions that were used for the establishment of the Amount A rule under Pillar 1[40].

There is additional friction arising out of continuous extensions for implementation of Pillar 1 solution. Given that the MLC for Pillar 1 was released to public in October 2023, it meant that complete implementation will be delayed until 2025[41], as against the earlier deadline of 2024[42]. This means that countries cannot levy newly enacted DSTs till 31st December,2024 or until the MLC comes into effect. This delay, as per OECD, is to achieve a harmonious consensus, but political disagreements remain. For instance, EU Commissions’ progress report on Pillar 1, published on 30th June 2023, has mentioned many issues with the Amount A component, such as the Marketing and Distribution Safe Harbour, DST measures, elimination of double taxation, etc[43].

For some other countries, the delay in the DST standstill itself is a prickly thorn. A prime example is that of Canada, which had plans to implement a DST, taking effect from January 2024. But, in 2021, the country agreed to pause implementation of its DST, actively participating in pillar 1 negotiations. But the country’s Department of Finance has said that they will implement their DST if the treaty to implement Pillar one does not come into force by January 1, 2024[44]. While the deadline has not been adhered to yet by Canada by implementing a DST, the Canadian Government is going ahead with its plans to implement a DST. The forthcoming legislation allows Canada the flexibility to determine the entry into force date of the DST, while simultaneously maintaining dialogue on Amount A[45].

But ultimately, Amount A must be seen for what it is, a compromise to break the status quo of unilateral DSTs creating significant hurdles for online businesses, in favour of a more stable international tax regime which reallocates taxing rights in an equal fashion. The long term benefits are seemingly beneficial for developing countries in the long run, reducing its administrative burdens and maintaining the revenues it had in the erstwhile DST regime, give or take 0.1%. High revenue MNE are primarily located in developed nations, whose taxing rights stand to be reallocated, but developed countries simultaneously enjoy the benefit from the abolition of DSTs, benefitting their resident internet companies who can do business in other jurisdictions with relative ease and a lower tax burden.

Conclusion

The increase in cross-border communication and the use of the Internet has allowed corporations in developed countries to leverage Web technologies to do business across borders, without a brick-and-mortar presence in any country they operate in outside their residence jurisdiction. The problem with such an arrangement was that source jurisdictions found themselves unable to tax the income derived by these technology-based MNEs due to a lack of a physical PE, a necessary prerequisite for taxation rights under the globally followed OECD DTAA model.

While developing countries adapted through the levy of unilateral digital taxes on such non-resident corporations, the fact remained that the fragmented nature of DSTs posed significant challenges to an international tax regime. The OECD in response has come up with the two pillar solution, and Amount A as a specific response to the widespread implementation of DSTs, offering an alternative to the same. Coming up next, the final article in this series will examine Pillar 2 and its consequences.

[1] OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital, Art, 5. ¶ 1(2017).

[2] OECD. (2011). Brief remarks on the public discussion draft concerning the interpretation and application of Article 5 (permanent establishment) of the OECD model tax convention, (Last visited October 14th, 2023), https://www.oecd.org/fr/ctp/conventions/49674929.pdf

[3] Action 1 Tax Challenges arising from digitisation, (Last visited January 1st, 2024), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/beps-actions/action1/

[4] OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital, Art, 10. ¶ 4(2017).

[5] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), (Last visited October 12th, 2023)

https://www.oecd.org/berlin/publikationen/43324465.pdf,

[6] Id

[7] The Finance Act, 2016, § 163, No.28, Acts of Parliament, 2016 (India).

[8] The Finance Act, 2020, § 153, No.12, Acts of Parliament, 2020 (India)..

[9] Daniel Bunn, Elke Asen, and Cristina Enache, Digital Taxation Around the World, Tax Foundation (2020), (Last visited October 15th, 2023), https://files.taxfoundation.org/20200527192056/Digital-Taxation-Around-the-World.pdf.

[10] European Commission, (Last visited on October 15th, 2023)

https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/fair-taxation-digital-economy_en.

[11] Id.

[12] Amadeus Global Travel v. Deputy Commissioner Income Tax, (2008) 113 TTJ Delhi 767

[13]Office of the United States Representative, Executing office of the President, Section 301 investigation, Report on India’s digital services tax, (Last visited on October 16th, 2023)

[14] OECD, International collaboration to end tax avoidance, (Last visited October 16th, 2023), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/

[15] OECD Pillars, Background to Pillar One, (Last visited October 16th, 2023), https://oecdpillars.com/pillar_one/pillar-one-summary-2/

[16] OECD/ G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, Statement by the OECD/ G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS on the Two Pillar Approach to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Janury 202, OECD/G20 Inclusive framework on BEPS 2.0, (Last visited 16th October, 2023), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-by-the-oecd-g20-inclusive-framework-on-beps-january-2020.pdf

[17] Office of the United States Trade Representative, (Last Visited 13th November, 2023), https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/enforcement/section-301-investigations/section-301-digital-services-taxes

[18] OECD, “Pillar One – Amount A: Fact Sheet” (Last visited 16th October 2023), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/pillar-one-amount-a-fact-sheet.pdf

[19] Deloitte, (Last visited 13th November 2023)https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/tax/in-tax-pillar-one-and-pillar-two-noexp.pdf

[20] Id.

[21] Leigh Thomas, Developing Countries get short shrift in global tax deal – Argentina, Reuters, (Last visited 13th November 2023), https://www.reuters.com/article/global-tax-argentina-idTRNIL1N2R31UH

[22] Dilasa Seth, India’s OECD tax deal may have revenue implications, say experts, Business Standard, (Last visited 13th November 2023), https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-s-oecd-tax-deal-may-have-revenue-implications-say-experts-121070500002_1.html

[23] Id.

[24] African Tax Administration Forum, (Last visited 13th November, 2023), https://www.ataftax.org/130-inclusive-framework-countries-and-jurisdictions-join-a-new-two-pillar-plan-to-reform-international-taxation-rules-what-does-this-mean-for-africa

[25] South Centre, Evaluating the Impact of Pillars One and Two (2022), (Last visited October 17th, 2023), https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/RP165_Evaluating-the-Impact-of-Pillars-One-and-Two_EN.pdf

[26] Amazon Inc, (Last visited 13th November 2023), https://s2.q4cdn.com/299287126/files/doc_financials/2023/ar/Amazon-2022-Annual-Report.pdf

[27] Progress report on Amount A of Pillar One, July 2022, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/frequently-asked-questions-progress-report-on-amount-a-pillar-one-july-2022.pdf

[28] OECD, (Last visited13th November 2023), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/revenue-impact-of-international-tax-reform-better-than-expected.htm#:~:text=Pillar%20One%2C%20designed%20to%20ensure,profits%20to%20market%20jurisdictions%20annually.

[29] U.S Department of the Treasury, Press release, Joint Statement from the United States, Austria, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom, Regarding a Compromise on a Transitional Approach to Exisitng Unilateral Measures During the Interim Period before Pillar 1 is in Effect, October 21st, 2021.

[30] Mona Barake, Elvin Le Pouhaer, Tax Revenue from Pillar One Amount A: Country-by-country Estimates, 2023. Halshs-04039288.

[31]The effect of the OECD’s Pillar 1 proposal on developing countries – An impact assessment, January 2022, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://webassets.oxfamamerica.org/media/documents/Pillar_1_impact_assessment_v2_25JAN2022.pdf?_gl=1*mbc3so*_ga*MTgyMTAyMzczOC4xNjkwNzk4MjEz*_ga_R58YETD6XK*MTY5MDc5ODIxMi4xLjAuMTY5MDc5ODIxMi42MC4wLjA.

[32] Digitalization and Taxation in Asia, (Last visited 10th January, 2024), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/13/Digitalization-and-Taxation-in-Asia-460120

[33] Navigating Complex Tax Consultations, An assessment of Kenya’s engagement in the Inclusive Framework, Kenya Revenue Authority, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://www.kra.go.ke/images/publications/Kenya-and-the-Inclusive-Framework—A-Case-Study-Report.docx.pdf

[34] Carlos Mureithi, Why Kenya and Nigeria haven’t agreed to global corporate tax deal, Quartz, https://qz.com/africa/2082754/why-kenya-and-nigeria-havent-agreed-to-global-corporate-tax-deal

[35] Kenya shifts to Adoption of Two-Pillar solution; Mulls more investor friendly Measures – Orbitax Tax News & Alerts, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://orbitax.com/news/archive.php/Kenya-Shifts-to-Adoption-of-Tw-52400

[36] Special Rapportuer on the right to development, 4th November 2022, Ref: OL OTH 107/2022, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=27648

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] A. Cobham, T. Faccio, V. FirzGerald, Global inequalities in taxing rights: An early evaluation of the OECD tax reform proposals, October 2019, p.6.

[41] Outcome statement on the Two-Pillar Slution to address the Tax Challenges arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/outcome-statement-on-the-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-july-2023.pdf

[42] International tax reform: OECD releases technical guidance for implementation of the global minimum tax, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/international-tax-reform-oecd-releases-technical-guidance-for-implementation-of-the-global-minimum-tax.htm

[43] Report from the Commission to the Council, Progress report on Pillar One, (January 10th, 2024), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=COM:2023:377:FIN

[44] Statement by the Deputy Prime Minister on international tax reform negotiations, Department of Finance Canada, (Last visited January 10th, 2024), https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2023/07/statement-by-the-deputy-prime-minister-on-international-tax-reform-negotiations.html

[45] Effective Government, a fair tax system, and a stable financial sector, (January 10th, 2024), https://www.budget.canada.ca/fes-eea/2023/report-rapport/chap4-en.html