In 2015, the Government of India launched a pilot project in 5 metro cities namely, Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi and Mumbai to test the feasibility of a paperless assessment of income tax. The project was further extended to two more cities. The project resulted in the adoption of completing various aspects of assessment proceedings through electronic means. The Central Board of Direct Taxes (“CBDT”) prescribed a revised format of notice issued by assessing officers for scrutiny. Thereafter, the CBDT vide instruction No. 03/2018 dated 20-08-2018 directed those assessments for Assessment Year 2018-19 to be conducted electronically through the e-proceeding facility.

Subsequently, there were two significant changes that took place with regard to the incorporation of electronic facilities for assessment proceedings – (i) the introduction of the E-Assessment Scheme, 2019 and the subsequent Faceless Assessment Scheme, and (ii) the insertion of Section 144B of the Income Tax Act, 1961 (“Act”).

I. RELEVANT PROVISIONS

A. E-Assessment Scheme, 2019: An Overview

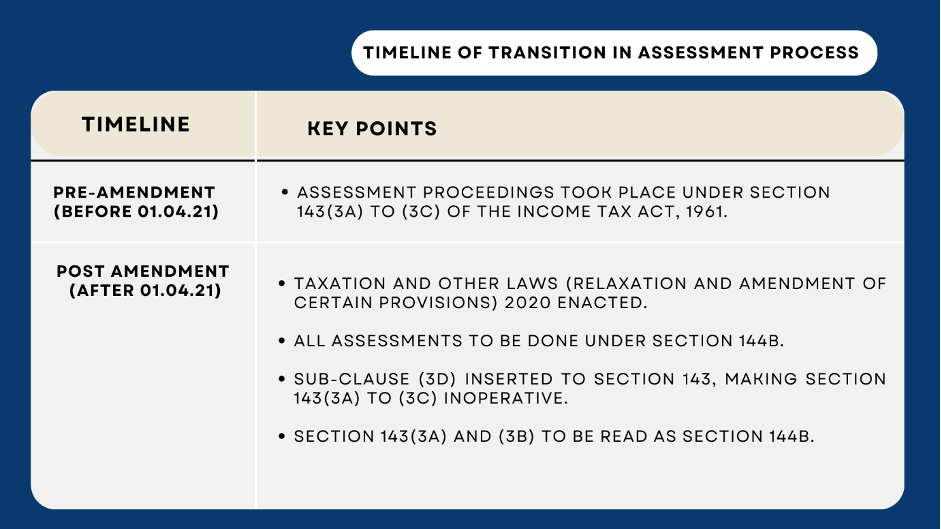

The Finance Act, 2018 inserted sub-clauses (3A) to (3C) under Section 143 of the Act, 1961. The aforesaid provision empowers the Central Government to formulate a scheme for the purpose of conducting assessments electronically.

By virtue of the said Amendment and in exercise of the powers bestowed under Section 143 (3A), the Central Government, in S.O. 3264 (E), dated 12.09.2019 introduced “E-Assessment Scheme, 2019”. It introduced the use of technology and electronic modes of communication in tax administration.

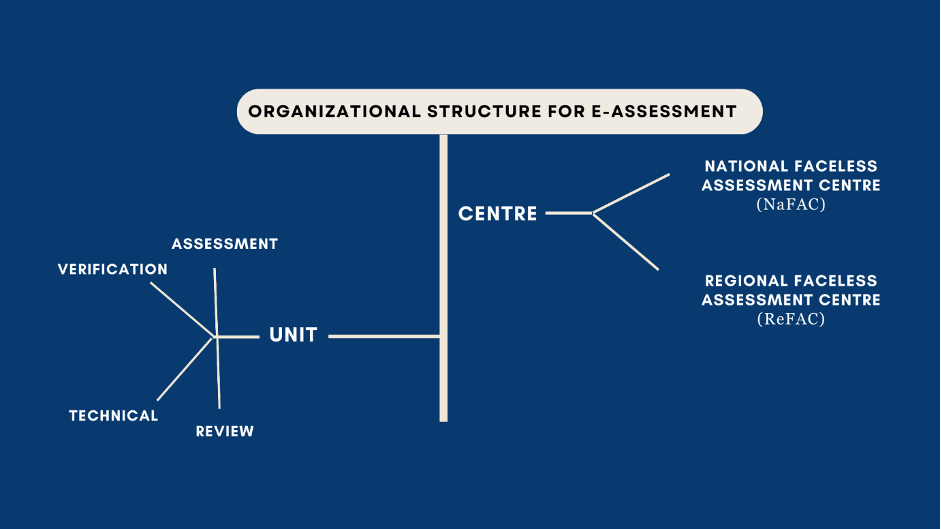

Under the new scheme, two new bodies were set up namely the National e-assessment Centre (“NeC”) and Regional e-assessment Centre (“ReC”). The function of the NeC was to conduct assessment proceedings in a centralized manner whereas the function of the ReC was to facilitate the same in the controlling region of the Principal Chief Commissioner.

Further, four units were set up to facilitate e-assessment proceedings – (i) assessment units; (ii) verification units; (iii) technical units; (iv) review units. Assessment units conducted assessment proceedings. The function of the verification units was verification of the proceedings being conducted. Technical units were responsible for the technical aspects of the proceedings such as providing advice or assistance in legal, accounting, forensic and other areas. Review units were responsible for reviewing the draft assessment order. The communication between the assessee and the units were through the NeC.

Assessment proceeding commences with notice being served on the assessee by the NeC under Section 143(2) of the Act. A reply can be filed within 15 days of receipt of the notice. Subsequently, the NeC shall assign the case to any Regional Assessment Centre through an automated allocation system. The four units work cohesively to draft, review and pass an existing order. The NeC is the main body that acts as a facilitator between the units amongst themselves and the assessee. The final assessment order prepared by the four units will be served to the assessee by the NeC and is asked to show cause as to why the order should not be passed. Upon considering the response of the assessee, the NeC shall prepare a revised order or pass the existing order.

B. Faceless Assessment: Section 144B of Income Tax Act, 1961

Currently, assessment proceedings take place in accordance with Section 144B of Act, 1961. The aforesaid provision was inserted vide the Taxation and Other Laws (Relaxation and Amendment of Certain Provisions) Act, 2020. Further, the said act also inserted sub-clause (3D) to Section 143 which provided that nothing in Section 143(3A) to (3C) would apply from 01.04.2021. Post 01.04.2021, the procedure prescribed under Section 144B is similar to the E-Assessment Scheme, 2019 such that it involves the National Faceless Assessment Centre (“NaFAC”) and Regional Faceless Assessment Centre (“ReFAC”). The functions of the said bodies and the units are virtually the same as that of the e-assessment Scheme, 2019.

Post the insertion of Section 144B of the Act, 1961, all assessment proceedings as of 01.04.2021 were to be conducted under the said section. Section 143(3A)-(3C) was inoperative. As of 01.04.2021, various assessment proceedings that were initiated under Section 143(3A) & (3B) now stood under the operation of Section 144B. To facilitate the same, the CBDT issued Circular F. No. 187/3/2020-ITA-I dated 08.04.2021. The said circular issued two directions:

- All orders/notices/letters/instructions/any other communications issued by ‘National Faceless Assessment Centre’ on or after 01.04.2021 bearing the logo and name ‘National e-Assessment Centre’ shall be deemed to have been issued by the ‘National Faceless Assessment Centre’.

- Notices, communications, orders, etc. issued by the NaFAC, wherever sections 143(3A) or (3B) are mentioned, the same shall be read as Section 144B of the Act.

The crux of this paper is to examine the validity of such orders and communications passed post 01.04.2021 and also the validity of the impugned circular.

II. ANALYSIS

A. Validity of Orders passed post 01.04.2021

The insertion of Section 144B of the Act resulted in a disruption in the ongoing assessment proceedings. Assessment proceedings commenced before 01.04.2021 were now subjected to the newly inserted provisions. Yet, in numerous cases, assessment orders were passed under Sections 143(3A) and 143(3B). The aforesaid orders were challenged before various High Courts in light of the insertion of Section 144B and Section 143(3D) of the Act.

In Gurgaon Realtech Ltd. v. national Faceless Assessment Centre Delhi before a division bench of the Delhi High Court, the petitioner challenged an assessment order dated 15.04.2021 passed by the Respondent under Section 143(3) read with Sections 143(3A) and 143(3B) of the Act on the ground that the impugned order was to be passed under Section 144B of the Act. The Division Bench upheld this contention and held that the impugned assessment order is invalid since it was to be passed under Section 144B of the Act. Similarly, Rani Promoter (P.) Ltd v. Additional Commissioner of Income Tax, the division bench while relying on Gurgaon Realtech held that Section 143(3D) of the Act was mandatory in nature and in light of the mandatory language employed therein, assessment orders were to be passed only under Section 144B of the Act. This position of law was reiterated by the Telangana High Court in M/s. Polepally Solar Parks Private Limited v. The National Faceless Assessment Centre and Others.

The aforesaid decisions rendered by the Delhi High Court and the Telangana High Court on the validity of orders and communications issued post 01.04.2021 under Section 144(3A) and 144(3B) fail to take into consideration Circular F. No. 187/3/2020-ITA-I dated 08.04.2021. The next part examines the constitutional validity of the circular.

B. Validity of Circular F. No. 187/3/2020-ITA-I Dated 08.04.2021

This section of the paper will determine the legal validity of the impugned circular dated 08.04.2021. It argues that the impugned notification is liable to be struck down by the courts of law on two main grounds – (i) the circular creates a ‘law’ and (ii) there is no saving clause for proceedings initiated before 01.04.2021 in the Taxation and Other Laws (Relaxation and Amendment) Act, 2020 which thereafter become non est.

I. Circular dated 08.04.2021 creates a ‘law’ which is beyond the scope of Section 119

The Circular dated 08.04.2021 is liable to be struck down as it is issued beyond the scope and ambit of Section 119 of the Act for two reasons – (i) the circular creates a “law” or runs contrary to the Statute and (ii) the circular interprets Section 143(3A)/(3B) which is beyond its domain.

It is a settled principle of law that a circular according to law would be binding on all officers and authorities along with the assessees, but no circular can go against the purpose of the Act even if it might deviate from the literal interpretation of the provisions of the Act. Moreover, such instructions can only supplement a statute or cover areas that the statute fails to cover but cannot go contrary or whittle down their effect. The scope of Section 119 is merely to issue orders, instructions and directions for ‘proper administration’ of the Act and the same cannot override the provisions of the Act.

Furthermore, the CBDT cannot substitute itself as the legislature and create a new “law”. In Jalgaon District Central Co-operative Bank Ltd. v. Union of India, the Court dealt with Circular No. 9 of 2002 of the CBDT which provided for a distinction between “members” of the co-operative society who are eligible for TDS under Section 194A(3)(v) of the Act, 1961. While the Act of 1961 does not define “member”, Section 2(6) of the Maharashtra Co-operative Societies Act, 1960 provides for the same. The Court held that impugned circular was outside the scope of Section 119 of the Act as it created a distinction between “members” which is not provided under the statute. Thereafter, the Court held that the impugned circular was passed by the CBDT by usurping the powers of the Parliament and the same cannot be done under the garb of Section 119 of the Act.

Similarly, the courts have on numerous instances struck down circulars or instructions issued by the CBDT if they exceeded the scope and ambit of Section 119. A circular can neither widen the ambit of a statutory provision nor can it curtail or modify the clear meaning of an expression used in the statute.

The circular dated 08.04.2021 is nothing short of an overreach of powers under Section 119 of the Act. The impugned circular while instructing that “Section 143(3A)/(3B)” in all official communications is to be read as “Section 144B” creates, in essence, a “new law” whereunder all official communications would be deemed to be issued under Section 144B of the Act. The same does not find its place in the Act as Section 143(3D) or Section 144B of the Act are silent on official communications that are already issued. Thereafter, this is a clear overreach of powers on part of the CBDT.

The second ground on which the circular is to be set aside is that it interprets a provision of the Act. In All Gujarat Federation of Tax Consultant v. CBDT, the Court held that it is well settled that interpretation of law is not the domain of CBDT and any interpretation, and if made by the CBDT, is not binding on the assessing authority or Courts insofar as questions of law are concerned. Such instructions are merely independent opinion of the CBDT which may or may not be accepted by the adjudicating authority. Similarly, in Reiter Machine Works Ltd. v. CIT, it was held that a circular cannot provide any guidance with respect to construction of a particular provision. Moreover, it is settled that the CBDT cannot also pre-empt a judicial interpretation of the scope and ambit of a provision and such tasks of interpretation are the exclusive domain of the courts.

The final interpretation of Section 144B as provided under the Circular can only be left in the hands of the courts to decide or for the Parliament to amend. The CBDT has no role in interpreting such provision.

II. There is no saving clause inserted vide the Taxation and Other Laws (Relaxation and Amendment of Certain Provisions) Act, 2020

According to the Circular, ongoing proceedings under the erstwhile provisions were deemed to be carried under Section 144B of the Act. While the legislature provided for an elaborate framework under Section 144B for faceless assessment, it neglected current ongoing proceedings initiated under Section 143(3A)/(3B). The legislature did not insert a saving clause while effectively providing for the expiry of the operation of Section 143(3A)/(3B). The absence of such a clause has wide ramifications on the legal status of proceedings initiated under the provisions thereunder.

In temporary statutes, the Legislature often inserts a “saving clause” similar to Section 6 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 to continue legal proceedings initiated under an expired statute. In instances, where there is no “saving clause”, it is a settled principle that proceedings against a person under a temporary statute ipso facto terminate as soon as the statute expires.

When a temporary statute expires, Section 6 of the General Clauses Act, 1897 which applies to repeals has no application. Thereafter, a “saving clause” is inserted by the legislature to prevent legal proceedings under the expired statute from terminating.

The genesis of this principle was established in Stevenson v. Oliver, wherein Park B, while distinguishing between repealed statutes and temporary statutes held “there is a difference between temporary statutes and statutes which are repealed; the latter (except so far as they relate to transactions already completed under them) become as if they had never existed; but with respect to the former, the extent of the restrictions imposed, and the duration of the provisions, are matters of construction.” This principle has also been widely accepted by Indian Courts.

In District Mining Officer v. Tata Iron and Steel Co., the Court dealt with Section 2 of the Cess and Other Taxes on Minerals (Validation) Act, 1992. The question dealt with by the court was whether because of the validation act, States were entitled to retain only the cess and taxes due upto 4th April 1991 or whether they were also entitled to collect the cess and taxes due upto 4th April 1991 but not collected till that date under Section 2 of the Validation Act, 1992. The Court held that the Validation Act did not enable the States to collect the cess and taxes not collected till 4 April. The Court reasoned that the effect of Section 2 was that the various invalidated state acts were temporary statutes expiring on 04.04.1991 and since there was no saving clause in the act, there could be no application of Section 6 of the General Clauses Act.

In Wicks v. Director of Public Prosecutions, the appellant was convicted for violating the Defence (General) Regulations, 1939, formulated under the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939. The Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939 expired in February 1946. Section 11(1) of the act read as: “Subject to the provisions of the section, this Act shall continue in force until the expiration of the period of six months beginning with the twenty-fourth day of August, 1945, and shall then expire.” Further, Section 11(3) provided: “the expiry of the act shall not affect the operation thereof as respect things previously done or omitted to be done.” The primary question dealt by this court was whether Section 11(3) authorised the prosecution and conviction of the appellant notwithstanding the expiration of the act. The court held that the appellant could be prosecuted even after the expiration of the act.

The above position of law was distinguished in Rayala Corporation v. Directorate Enforcement. Rule 132A of the Defence of India Rules, 1962, which related to the prohibition of dealings in foreign exchange was amended by the Amendment Rules, 1965, “omitted except as respects things done or omitted to be done under that rule.” The question dealt by the Court in the case was whether a prosecution in respect of contravention of Rule 132A could be commenced after the Rule was omitted. The Court ruled that the same cannot be done as the amendment only affords protection to “things already done under that rule”. Hence, a new prosecution cannot be commenced.

In Keenara Industries v. Income Tax Officer, the assessee was issued reassessment notices after 01.04.2021 under the erstwhile Sections 148 to 151 of the Act. Further, the time limit for issuing such notices were amended by the Finance Act, 2021 and the aforesaid notices were not issued in accordance to the amended provisions. The Gujarat High Court in the said case observed that the Finance Act, 2021 did not contain a savings clause to protect proceedings under the erstwhile Finance Act, 2021. Hence, the same would end the possibility of any fresh proceedings under the erstwhile provisions. The Uttar Pradesh High Court held a similar ruling in respect to reassessment notice issued under the erstwhile provisions in Rajiv Bansal v. Union of India.

The above decisions merely buttress the legal position that when provisions of a statute expire or cease to apply on a particular date, the proceedings under the said provision cease to exist unless actions or things done under that rule are provided as an exception.

The Statute presents two positions of law namely, the first, before 01.04.2021 wherein Section 143(3A)/(3B) would apply and the second, after 01.04.2021 wherein Section 144B would apply. Both these provisions deal with either proceedings initiated before 01.04.2021 or after 01.04.2021. However, the amendment does not deal with on-going proceedings. The absence of a saving clause implies that proceedings initiated under Section 143(3A)/(3B) stand terminated as of 01.04.2021. The same cannot be remedied by an executive instruction which provides that a provision must be read as another provision. The idea that instruction is valid does away with the concept of saving clause during the expiry of statutes. Therefore, proceedings initiated under Section 143(3A)/(3B) of the Act are terminated and stand non-est in the eyes of law.

III. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

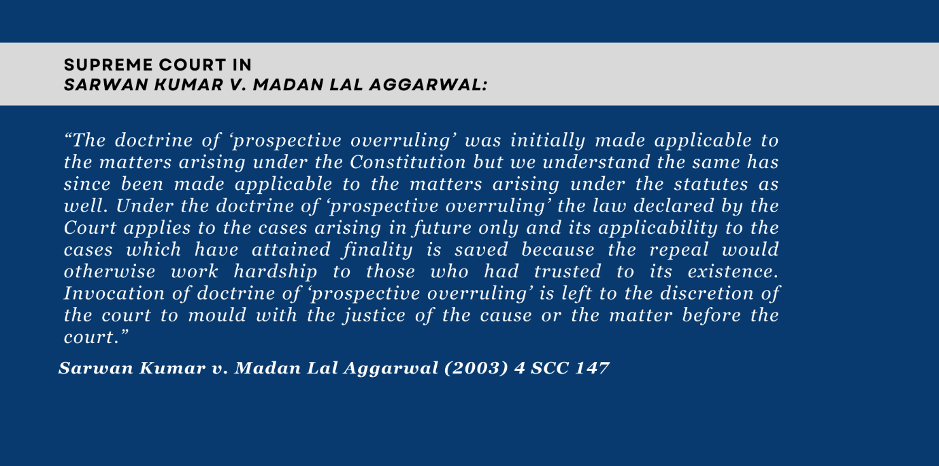

The circular dated 08.04.2021 issued by the CBDT is liable to be set aside on two main grounds as discussed above – (i) the circular dated 08.04.2021 creates a “law” or is contrary to the provisions of the Act and (ii) the absence of a “saving clause” would terminate all ongoing proceedings post 01.04.2021. In respect of those assessment proceedings that are still pending, the Court ought to set aside the circular and invoke the doctrine of prospective overruling. This ensures that those assessment proceedings that are completed or ongoing are not affected by the ruling of the court in case the circular dated 08.04.2021 is struck down. Hence, in case, the court adopts prospective overruling, the Revenue can still proceed with the proceedings in question while still striking down the circular.

In Sarwan Kumar v. Madan Lal Aggarwal, the Supreme Court observed:

Another solution that can be adopted by courts is to pass orders construing all communications and notices issued post 01.04.2021 under Section 144(3A)/(3C) of the Act to be deemed to have been issued under Section 144B of the Act. In Union of India v. Ashish Kumar Agarwal, 9000 reassessment notices were challenged before various High Courts on the ground that they were passed under the unamended Act on or after 01.04.2021. The Supreme Court observed that striking down all notices would frustrate the object and purpose of proceedings. Hence, it directed a one-time measure wherein all notices issued under the erstwhile Section 148 of the Act was deemed to have been issued under the new Section 148A of the Act. This solution would ensure that proceedings would remain ongoing while providing it with legal recognition.

Editorial Note: This post was edited by Ishika Garg, Priyanshi Chokshi and Anuraag Bukkapatnam, and the infographics were made by Kshipra Shukla.