This series is aimed at examining the framework of the international taxation regime and the role of developing countries therein. It will discuss the evolution of tax treaties and the academic critiques from a Third World perspective, analysing the structural biases of these agreements. The following article will introduce and discuss the Eurocentric origins of Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (“DTAAs”) along with the closely connected origins of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”). To introduce the next article in this series, this post briefly examines the effects of the OECD model on the countries which belong to the third world. This series was written by Samvedh, Kartheek, Dhanush, and Aditya from the CTL.

History of Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements

The first comprehensive international treaty expressly concerned with the prevention of double taxation was signed between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Prussia (present day Germany) on 21st June, 1899 (“Treaty”). To understand the legal history of this Treaty and DTAAs in general, we need to locate them in the political history that they are a part of, alongside the legal developments which enabled countries to form such agreements. This part of the paper discusses the political climate in nineteenth-century Europe which enabled the creation of the first DTAA. Most modern tax agreements are based on the OECD Model Tax Agreement which in turn is greatly connected to the principle of ‘reciprocity’.

A. Principle of Reciprocity and Early Tax Treaties

It is extremely important to start the story of DTAAs with the principle of ‘reciprocity’ as it forms the foundation of international taxation.[i]Reciprocity may be defined as ‘the granting by one nation of certain commercial privileges to another, whereby the citizens of both are placed upon an equal basis in certain branches of commerce’.[ii] While reciprocity is a condition theoretically attached to all legal norms of international law, it is not the basis of all commercial agreements.

The origins of the principle of reciprocity in international commerce can be traced to shipping law. An early example involves the Dutch introducing a law which provided exemptions from license tax to foreign ships from countries that granted a similar exemption to Dutch Ships.[iii] Similarly, the Great Britain introduced a law that allowed countries to import goods in their own ships or British ships, if they allowed British ships as well.[iv] These led to a substantial increase in navigation in British ships. Following this, there were demands for decreased trade restrictions founded on the policy of reciprocity.

These early treaties based on reciprocity also gave way to the most-favoured-nation treatment (MFN) principle following the conclusion of a trade agreement between France and Great Britain. Reciprocity was an important element in all tax treaties since then and was even found in the Treaty between Austro-Hungary and Prussia. The Prussian Parliament enacted a law giving the Minister of Finance the authority to enter into similar agreements for the avoidance of double taxation with other countries based on the principle of reciprocity.

These early tax treaties also attempted to establish how to alleviate double taxation and identified methods for providing relief from it. This was to be achieved by one jurisdiction unilaterally not imposing tax on income earned in another jurisdiction. They further adopted fundamental principles of allocating taxing rights based on the source of income or the residence of the taxpayer.

B. The First DTAA, its provisions and political context

Before two countries came to cooperate to alleviate the problem of double taxation, there were various tax cooperation agreements which regulated administrative cooperation between countries with regard to taxation matters. The first such tax cooperation agreement was signed between France and Belgium in 1843. Under this agreement, officials would share documents and information which would assist in the collection of taxes imposed by the laws of the two countries. Participation in these treaties reflected close proximity in terms of territory and political history.

The first DTAA, as highlighted earlier, was signed between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Prussia on 21st June 1899. It was lauded as an auspicious event of international comity. In 1896, Austria introduced a new taxation law which reformed the tax system and introduced various forms of tax, such as personal income tax, acquisition tax, a trade tax, a pension tax, and a remuneration tax. The instances of double taxation increased which could arise due to dual nationality or residence, residence in one country but nationality in another, or movement between the countries such as working in one country but residing in another. This was especially common in the border areas where residents extensively engaged in cross-border activity. Double taxation of these border residents was considered an unfair burden.[v]

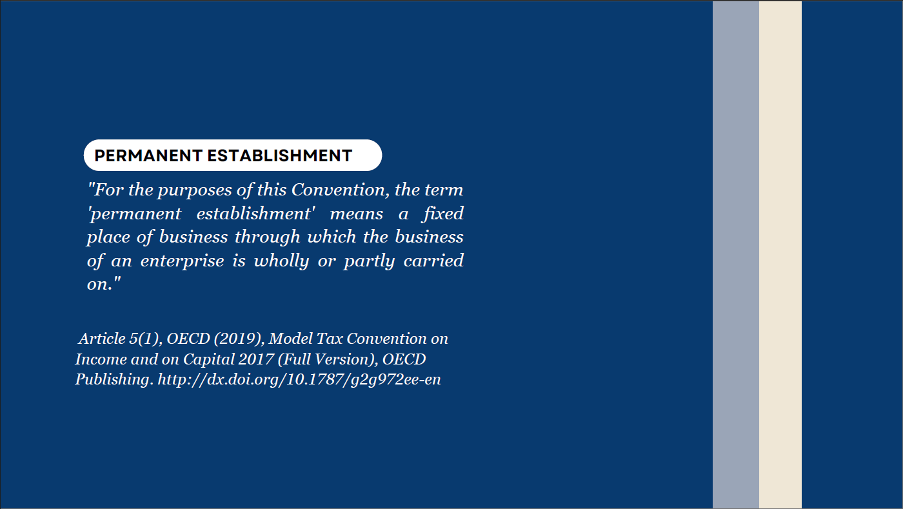

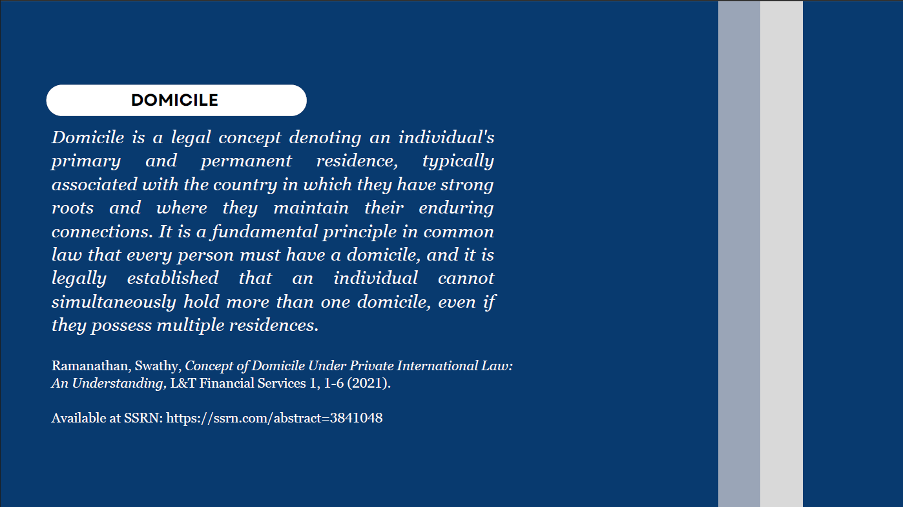

These problems were addressed by allocating certain taxing rights to one country on the basis of domicile and to the other on the basis of source of income. For example, the right to personal taxes were given to the country of domicile, while the country of source which had the property located within could tax that property or the business. The treaty also utilised the Permanent Establishment (“PE”) concept and allocated the right to tax business profits to the country where the PE was established. However, partial double taxation continued as all issues did not find a compromise or solution.[vi]

The Treaty can be located in the political context of European power changes following the Concert of Vienna in 1811 and the failure to establish a German nation. Through the 19th century, there were wars and alliances seeking to consolidate power in and around Germany. Prussia became the dominant power and chose Austro-Hungary as its foreign partner which led to the creation of a dual alliance, which later became a triple alliance with the inclusion of Italy. They sought to consolidate their relationship with a trade treaty based on low tariffs as a retaliation to the economic threat from France. The goal of the Triple Alliance was to strengthen itself economically and showcase itself in Germany’s economic policy. Thus, the DTAA was primarily another component of a complex political and economic alliance between Austro-Hungary and Prussia. Austro-Hungary soon concluded another DTAA with Liechtenstein in 1901.[vii]

The primary goal of these tax treaties was to enable the movement of people between states without the burden of double taxation. These treaties were developed on the basis that double taxation was unacceptable when it prevented the free movement of people. They were not concerned with generally alleviating double taxation. From the context, we can also notice that such movement was only encouraged into territories of allies. It can also be seen that double taxation of certain kinds of investments was acceptable as individuals would have the opportunity to make an alternate form of investment.[viii]

C. Institutional Developments Shaping Tax Treaties

As the global economy continued to grow and become complex, the need for standardized terms for DTAAs began to be felt. This paved the way for international institutions that sought to create ‘Model Tax Conventions’ which would form a standard template while member countries negotiated tax treaties amongst themselves. The first such attempt at creating such conventions can be traced to the League of Nations.

i. League of Nations

The League of Nations entered the field of international taxation in the backdrop of a post-war revival as it was formed after the conclusion of the First World War (WWI). Following the end of WWI, there was renewed interest in the conclusion of DTAAs. This was primarily due to an exacerbated burden of double taxation faced by the people owing to the increases in taxation. Double taxation also became a form of limitation on the international mobility of both people and capital, hampering post-war reconstruction efforts.

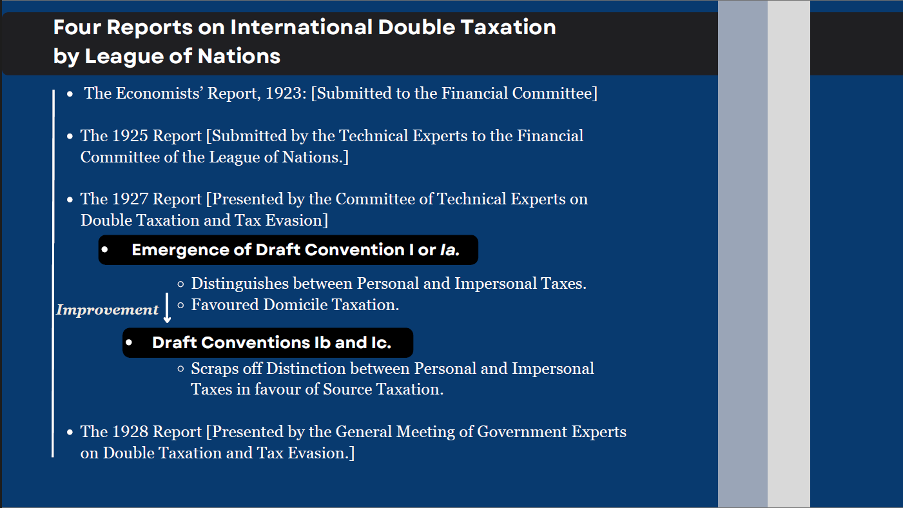

Following the creation of the League of Nations, several treaties were concluded. This included the first multilateral tax treaty in the form of the Rome Convention. The League of Nations produced four reports on international double taxations: the Economists’ Report,[ix] the 1925 Report,[x] the 1927 Report,[xi] and the 1928 Report.[xii] The 1928 report was extremely influential as it included the first model treaties on double income taxation. The 1928 Models were considered to be one of the few successes of the League’s work.

The 1925 Report and its Overarching Considerations

The drafting of the 1925 report takes particular importance as it included several resolutions addressing double income taxation and the determination of fiscal domicile.[xiii] These laid the foundation for the League’s 1928 Models. They officially recognised the reality that source countries would not give up the imposition of schedular taxes and that the imposition of the general income based on residence was growing. It is important to keep in mind that the initial aim of the committee was to combat tax evasion more than limiting double taxation.

The 1925 Report was guided mainly by three considerations – Spirit of Compromise, the Need for Revenue, and Experts as Technicians.[xiv] According to Edwin Seligman, the Spirit of Compromise developed only after the first meeting of the Expert Committee ended and led to a warm and friendly environment, deliberating for the world with an international perspective in mind.[xv]

The broad influences on the work of the 1925 experts were the existing treaty practice, the Economists’ Report, and practical considerations.[xvi] However, practical considerations such as domestic law, administrative simplicity, and revenue needs had the greatest influence on the drafting of these resolutions. It also came with a recommendation to convene an expanded conference of government officials to develop draft international treaties based on the Report.

The 1928 Report and the Three Model Conventions

The first Draft Model Convention came from the efforts of the 1927 Report. The 1928 Report’s Draft Conventions were a significant milestone in the evolution of DTAAs. They contained three model conventions on prevention of double taxation. These prevailed as the model for OECD and substantially influenced future tax treaties.

The first model, referred to as Draft Convention I or Ia, was an updated version of the draft convention made by the 1927 Report. One of its important features is that it distinguishes between personal and impersonal taxes. The second and the third models, referred to as Draft Conventions Ib and Ic, do not make such a distinction. This removal was considered a huge improvement from Ia.[xvii] Some of the key issues that the experts deliberated upon while drafting Ia are Issues of Developing Countries, Distinction between Impersonal and Personal Taxes/Alternative Draft Conventions, New Countries, Bilateral versus Multilateral Treaties, and Participation of Non-Members.[xviii]

Even in the initial stages of the Model Tax Convention, a key issue faced by policy makers related to the balancing of interests between capital-importing and capital-exporting countries. The Model Conventions at this stage were primarily in favour of capital-exporting countries, with many developing countries agreeing to adopt them hoping that the same leads to improvement in their economic relations. A few experts considered the Ia to be favoring domicile taxation. All the capital-importing countries favoured source taxation. Experts also implicitly approved of the proposed approach of bilateral treaties. They also had discussions on various technical aspects of the law, such as deciding the persons covered, taxes covered, income from immovable property, and interest. They discussed the general rules and the exceptions that could be meted out to the general rule.[xix] These narratives provide useful insights into discussions that continue today.

ii. OECD

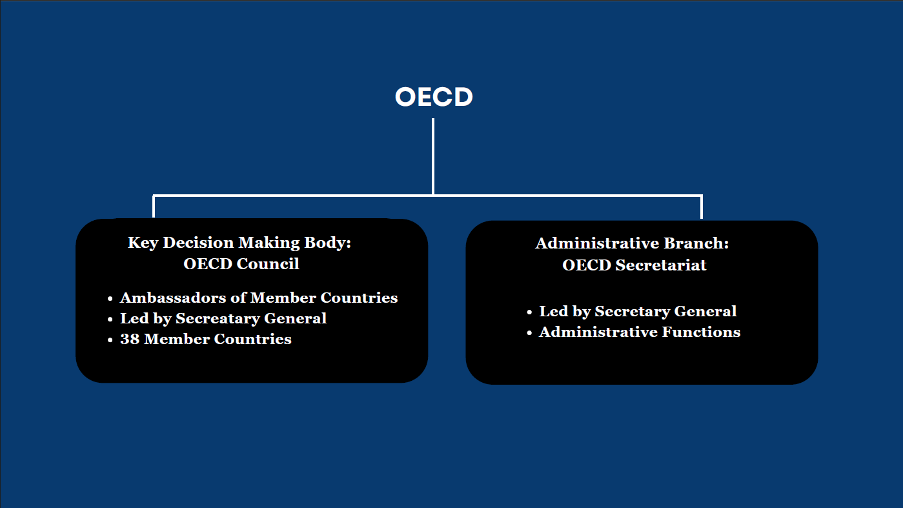

The Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) was formed in 1948 to oversee and administer American aid in the framework of the Marshall Plan. In 1961, the OECD was formed and superseded the OEEC, after the Convention on the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development was signed. It currently has 37 member countries, which include the largest economies in the world and its members account for three-fifths of the world GDP. The international taxation rules for multinational companies are established, along with the publication of a Model Tax Convention. This Convention serves as a blueprint for distributing taxing responsibilities between countries.

“Consensus Among Member Countries”

The key decisions are made by the OECD Council, composed of member countries’ ambassadors and led by the Secretary-General. The structure of the OECD comprises various elements that support its operations and decision-making procedures. Its foundation lies in its membership, which currently consists of 38 countries, predominantly representing developed economies. The OECD Secretariat, led by the Secretary-General, acts as the administrative branch of the organization.

Decisions within the OECD are primarily reached through consensus among member countries. Unlike the “one country, one vote” principle, decision-making power is primarily concentrated among the developed countries, often referred to as the “wealthy” or “rich” countries. This concentration of power is a result of historical circumstances and the economic influence wielded by these countries.

“Committees and Functions of OECD”

The decision-making process of the OECD involves various committees and working groups composed of representatives from member countries. These entities cover a wide range of policy areas, such as economics, finance, trade, environment, and education. They play a crucial role in formulating recommendations, conducting research, and developing policies, which are then presented to the Council for consideration.

In recent years, the OECD has been actively striving for inclusivity and engagement with non-member countries through various initiatives. It has established partnerships and cooperation agreements with several non-member economies, thus enabling their participation in specific activities and contributions to policy discussions.[i] Nevertheless, as will be highlighted in a later post criticising the legitimacy of the OECD, decision-making authority within the organisation remains skewed and primarily vested in the developed countries.

OECD Model Tax Convention

The 1928 model bilateral convention and the subsequent Model Conventions of Mexico in 1943 and London in 1946 paved the way for the OEEC to adopt its first recommendation concerning double taxation on 25th February, 1955. Neither of the previous model conventions were used due to gaps that existed on several essential questions. Post WW2, there was a need to set the economic interdependence of OEEC member countries within a legal framework to prevent international double taxation. The network of bilateral tax treaties within OEEC, and subsequently OECD countries, was inadequate and there existed a need for harmonisation of these conventions to present uniform rules, principles, definitions, and methods.

The Fiscal Committee thus set out to prepare a draft convention towards these ends and prepared four interim reports between 1958 and 1961 before submitting the final report in 1963 titled Draft Double Taxation Convention on Income and Capital. The OECD Council further adopted a recommendation to avoid double taxation and called upon member countries to adhere to the Draft Convention. The changes in the tax systems of member countries, increase in fiscal relations, and new developments concerning complex business organizations, among others, led to the publication of a revised convention in 1977. A 1992 revision was introduced to take into account the views of non-member countries, international organizations, and other parties. Since 1992, ten such updates have been made to reflect periodic updates and the views of member countries, the most recent version having been published in 2017.[xxi]

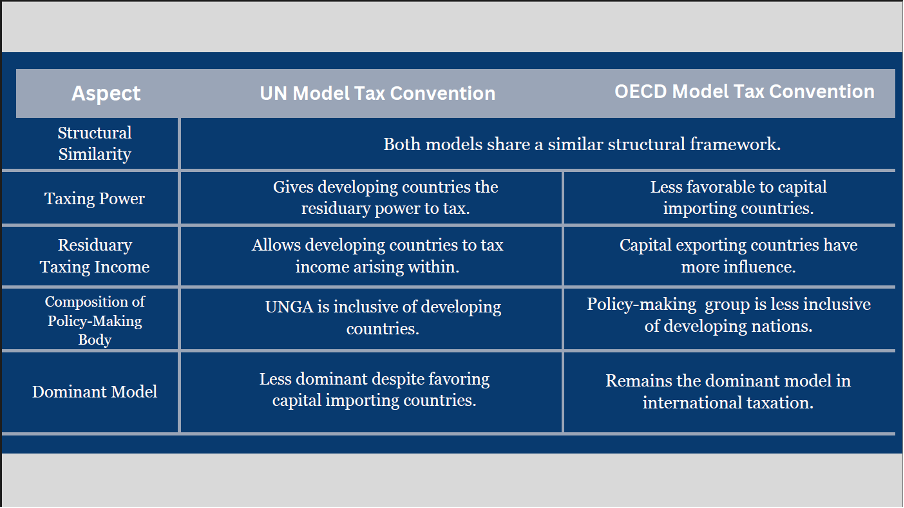

A key feature of the OECD model is its emphasis on ‘residence’ as the determining factor for taxing income. While source countries are provided certain rights to tax business profits, the same can be taxed only when the non-resident conducts business in the source country through a PE. Furthermore, most DTAAs based on the OECD model also restrict the ability of source countries in taxing others forms of passive income (such as royalties, fees for technical services, capital gains, etc.) by imposing a cap on the maximum withholding tax permissible for the same. The residuary powers of taxation remain with the country of residence under this model convention.

UN Model Tax Convention

Alongside the development of the OECD Model Tax Convention, the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations (UN) adopted resolution 1273 (XLIII) in August 1967, recognizing the desirability of bilateral tax treaties between developed and developing countries. In furtherance of this agenda, the Secretary-General of the UN set up the Ad Hoc Group of Experts on Tax Treaties between Developed and Developing Countries in 1968, comprising of experts and officials from developed and developing countries. The deliberations of the Ad Hoc Group led to the publication of the Manual for the Negotiation of Bilateral Tax Treaties between Developed and Developing Countries in 1979, followed by the release of the United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention between developed and developing countries in 1980.

However, the increasing shift in focus to the tax impact of transfer pricing, tax havens, and globalization led the Ad Hoc Group (renamed in 1980 as the “Ad Hoc Group of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters”) to revise the old Model Convention in 1999 and publish it in 2001. This was also fueled by the recurring updates to the OECD Model Convention. The Ad Hoc group was upgraded to a committee in 2005 and is composed of 25 members nominated by countries and appointed by the Secretary-General.

While the UN and OECD conventions are largely similar in structure, the UN Model gives developing countries the residuary power of taxing income that arises within its territories. As a result, the UN Model is more favourable to capital importing countries than the OECD Model. The difference in approaches can also be understood from the composition of the UN General Assembly, which is far more inclusive of developing countries than the OECD’s policy making group.

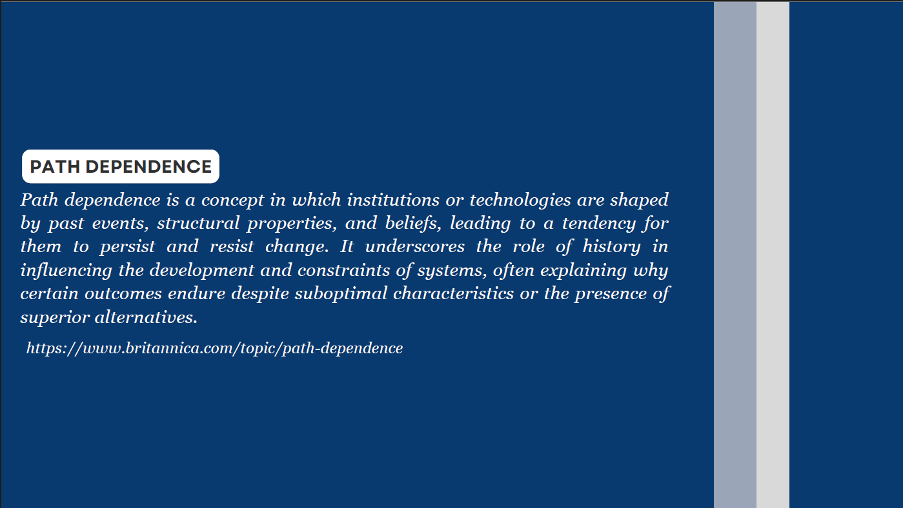

Yet, even with the emergence of alternative options such as the UN Model Convention, the OECD model tax convention remains the dominant model followed today. To understand why the OECD model achieved supremacy despite the numerical majority of countries preferring the UN Model convention, it would be worthwhile to examine a phenomenon termed as the ‘path dependency effect’.

Path Dependency and the Third World

As stated earlier, modern tax treaties significantly borrow from early tax treaties made by European Countries before WWI and then by the Model Tax Treaties made by the League of Nations. As stated by Sunita Jogarajan, “the fact that the fundamentals of modern tax treaties are essentially the same as their nineteenth century counterparts suggests that there is a strong element of path dependence in the development of tax treaties.”[xxii] She uses the term path dependency to simply mean “the dependence of economic outcomes on the path of previous outcomes, rather than simply on current conditions.”[xxiii] It is to be further noted that if tax treaties or, more broadly, attempts to address double taxation, were developed based on the current economic and political climate, then it is extremely possible that substantial differences would emerge.

A number of scholars have commented on the problems that bilateral tax treaties bring about in the current international commercial environment.[xxiv] These problems include their inconsistencies with the multilateral nature of business, limitations of existing treaties on unilateral action, and many more. While new solutions have been proposed, the adherence to past practice is likely due to the fact that it is largely successful for developed countries. The analysis of pre-WWI treaties shows that the political and economic conditions within countries are important precursors to a change in international taxation governance.

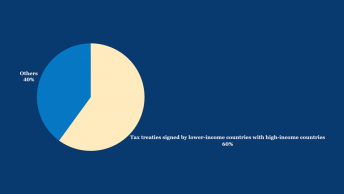

It is also to be noted that most tax treaties that were signed between two countries always involved an economically superior nation. Taking the Austro-Hungary and Prussia example itself, Prussia was an economically dominant state. Later articles will show how developing countries are willing to enter into such treaties with countries even if it leads to a loss of their own revenue due to the First World rhetoric that they allow entry into stronger markers, economic integration, and increase investment into their country. These have in turn restricted developing countries’ ability to collect urgently needed revenue from income earned in their jurisdiction. These tax treaties are also against normative principles of international tax, as they deny low-income countries’ right to collect that tax. Few have described these treaties as ‘poisoned chalice’ for developing countries.[xxv]

The skepticism over the questioning of tax treaties by scholars is a recent phenomenon. Scholarly research notes that low-income countries should fiercely guard their jurisdiction to tax. As highlighted earlier, there has been a constant tussle between capital exporting and capital importing countries. South American countries largely refused to enter tax treaties owing to this reason. However, they were integrated with the promise of greater integration into the world economy. As later articles will demonstrate, these premises have been challenged by scholars as being plainly false.

Conclusion

The path dependency in the development of tax treaties has perpetuated the influence of early models, favouring capital-exporting countries and is often disadvantageous to developing countries. Bilateral tax treaties between economically superior countries and developing countries have been seen as a means to attract investment and integrate into the global economy. However, these treaties have sometimes limited the ability of developing countries to collect much-needed revenue from income earned within their jurisdiction.

In recent years, scholars have questioned the efficacy and fairness of tax treaties, highlighting inconsistencies with the multilateral nature of business and the limitations they impose on unilateral action by countries. The following post in the series will consider the inequitable effects of these treaties, their impact on the sovereignty of Third World countries, and the exploitation such countries face when entering into tax treaties with developed countries and the institutions controlled by them.

Editorial Note: This post was edited by Samvedh Bagavadeeswar and Ishika Garg, and the infographics were made by Kshipra Shukla. The article was written based on the initial skeleton developed by Anuraag Bukkapatnam.

[i] Sunita Jogarajan, Prelude to the International Tax Treaty Network: 1815 – 1914 Early Tax Treaties and the Conditions for Action, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 31, No. 4 pp 679-707.

[ii] JL Laughin and HP Willis, Reciprocity (The Baker & Taylor Co 1903) 1.

[iii] J Herndon, Relief from International Income Taxation: The Development of International Reciprocity for Prevention of Double Income Taxation (Callaghan & Co 1932) 16.

[iv] Supra n 1, at 5-6.

[v] Supra n 1, at 690.

[vi] Supra n 1, at 691.

[vii] Id., at 691-692.

[viii] Id., at 706.

[ix] G. W. J. Bruins et al., Report on Double Taxation: Submitted to the Financial Committee, League of Nations, 1923.

[x] League of Nations, Double Taxation and Tax Evasion: Report and Resolutions Submitted by the Technical Experts to the Financial Committee of the League of Nations (1925).

[xi] League of Nations, Double Taxation and Tax Evasion: Report Presented by the Committee of Technical Experts on Double Taxation and Tax Evasion (1927).

[xii] League of Nations, Double Taxation and Tax Evasion: Report Presented by the General Meeting of Government Experts on Double Taxation and Tax Evasion (1928).

[xiii] Sunita Jogarajan, Book on Double Taxation and the League of Nations, Chapter 3: Personality, Politics, and Principles: The Drafting of the 1925 Resolutions on Double Taxation, 2018.

[xiv] Id., at 27-29.

[xv] Edwin Seligman, Double Taxation and International Fiscal Cooperation (Macmillan, 1928), 143.

[xvi] Supra n 12, at 81-83

[xvii] Sunita Jogarajan, Book on Double Taxation and the League of Nations, Chapter 7: One Beget Three: The Drafting of the 1928 Model Tax Treaties on Double Income Taxation, 2018, 182.

[xviii] Id., at 188-92.

[xix] Id., at 203-21.

[xx] Trade and Agricultural Directorate, OECD, The Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade Policy (April 2015), https://www.oecd.org/countries/centralafricanrepublic/Participation-Developing-Countries-GVCs-Policy-Note-April-2015.pdf.

[xxi] OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital 2017 (Full Version), OECD Publishing, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/g2g972ee-en.

[xxii] Supra n 1, at 705.

[xxiii] Paul David, Path Dependence and the Quest for Historical Economics: One More chorus of Ballad of QWERTY, Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers _020, University of Oxford, Department of Economics, 1997.

[xxiv] M Rigby, A Critique of Double Tax Treaties as a Jurisdictional Coordination Mechanism, Australian Tax Forum, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1991: 301- 427.

[xxv] Supra n 1, at 706.