The online gaming industry in India is experiencing rapid growth and has a steadily increasing user base. However, despite its popularity and potential for further expansion, the industry faces a significant hurdle from a recently proposed decision of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Council. According to the decision, the GST regime would now categorize online gaming alongside betting and gambling activities, subjecting it to a heavy tax burden of 28%. This article delves into the implications of such a tax classification, exploring how it could stifle industry growth, undermine its competitiveness, and impact the broader landscape of allied sectors. Additionally, the article examines the moral and constitutional arguments behind this taxation approach and whether it aligns with established legal principles or risks yielding unintended consequences. As the gaming industry seeks to flourish in India, finding a balance between taxation, regulation, and promoting its skill-based nature becomes crucial for its sustainable growth.

A. THE CURRENT TAX REGIME VIS-À-VIS THE PROPOSED TAX REGIMES

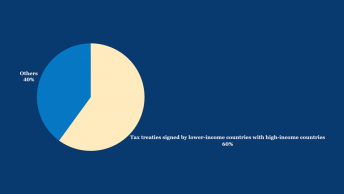

The proposed GST implementation aims to include online gaming within the exceptions provided in Clause 6 of Schedule III of the CGST Act, 2017. Currently, Schedule III states that no actionable claims except lottery, betting, and gambling are subject to GST. As online gaming also falls within the ambit of an actionable claim, the GST Council’s decision suggests a possible amendment to Clause 6 to broaden the scope of exceptions in order to levy GST upon the pot value in online games, wherein the pot value refers to the entire amount paid to enter the contest.

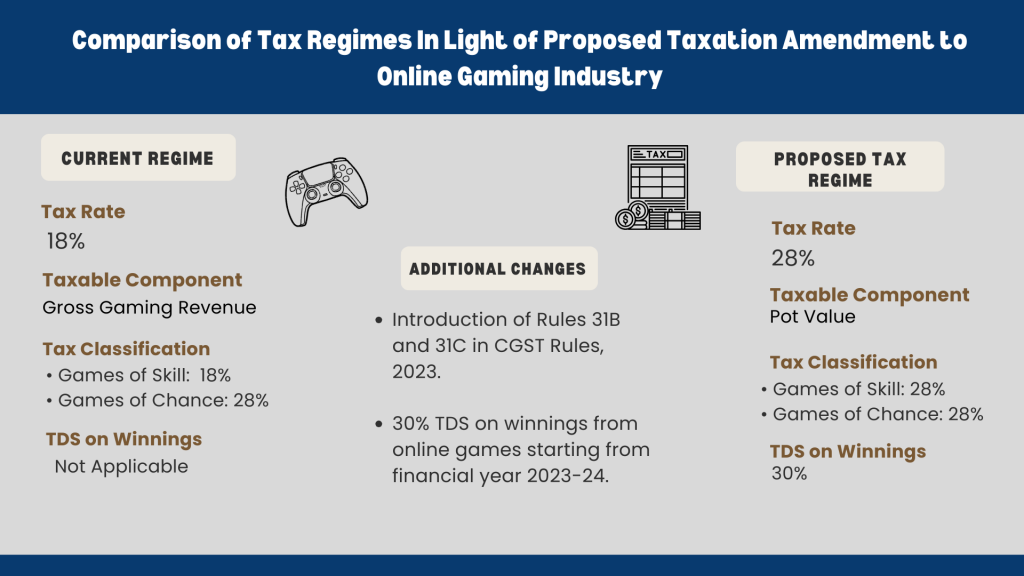

The current GST regime distinguishes between games of skill and games of chance. The former is taxed at 18%, while the latter is taxed at a higher rate of 28%. The 18% tax is currently only applicable to the platform’s service fee or the Gross Gaming Revenue (GGR) which is the difference between the amount wagered and the amount won. GGR thus refers to the fee charged by an online gaming platform for facilitating the participation of players in the game. However, the GST Council has proposed to impose this higher tax rate on the pot value. In light of this recommendation, the CBIC vide Notification No. 45/2023 has inserted Rules 31B and 31C to the Central Goods and Services Tax (Third Amendment) Rules, 2023 which lay down that the value of supply of online gaming and actionable claims in case of casinos shall be the total amount paid by the player. Essentially, this translates to the levy of tax upon the pot value instead of the GGR as is the current practice.

Additionally, the 2023 Budget has facilitated the imposition of a 30% tax deduction at source (TDS) on total winnings from online games, applicable from the financial year 2023-24 under Section 194BA of the Income Tax Act, 1961. Guidelines for the same have been issued by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT). Resultantly, there is now a heavy tax burden on the online gaming industry.

B. IMPACT OF THE PROPOSAL – STIFLING OF THE INDUSTRY?

i. The Skill v. Chance Conundrum

The GST council has categorized online gaming on the same lines as casinos and horse racing, which are in essence betting and gambling activities. Such activities are predominantly games of chance, attracting a levy of 28% GST. In this regard, it is pertinent to understand that based upon the principle of skill versus chance, the Supreme Court has acknowledged that there is an element of chance in games which involves shuffling and dealing of cards as its distribution is contingent upon how the cards are placed in the shuffled deck. However, despite this inherent element of chance, games such as rummy requires a considerable amount of skill to formulate a strategy in holding and discarding the cards. Therefore, such a game is not a game of entire chance but predominantly a game of skill. Extrapolating this reasoning to the instant case, it is submitted that the ‘predominant’ or ‘substantial’ nature of the game is to be taken into consideration when levying a tax as online gaming essentially involves the display of a player’s knowledge, skill and expertise.

In this regard, various judicial pronouncements which have expounded upon certain facets and highlighted the differences between games of ‘skill’ and ‘chance’ can be referred to. It has been held that a substantial degree of the exercise of skill is necessary to avoid the stigma of gambling. This jurisprudence was further developed in the landmark case of K.R. Lakshmanan v. State of T.N., wherein the Apex Court defined a game of chance to be that which is determined entirely or in part by luck. In contrast, a game of skill is primarily determined on the basis of ‘superior knowledge, training, attention, experience and adroitness of the player’. Accordingly, in games of chance, the player is unable to influence the result of the game through his mental or physical skill and winning is determined by pure luck alone.

With the rapid emergence and boom of the gaming industry, tax administrators have sought to bring online gaming within the ambit of games of chance which has explicitly been struck down by the judiciary on numerous occasions. Placing reliance on the bifurcation between games of skill and chance, the Punjab and Haryana High Court in Varun Gumber v. UT of Chandigarh has classified organized internet gaming tournaments and fantasy sports as games of skill. It was observed that winning in games such as Dream11’s fantasy sports are determined by a user’s attention, judgement and superior knowledge. Interestingly, a review bench of the Supreme Court rejected the SLP filed against the aforesaid judgement of the Punjab and Haryana High Court and upheld the classification of fantasy sports offered by Dream11 as a game of skill. In a similar vein, the Bombay High Court in Gurdeep Singh Sachar v. Union of India applied the principles laid down by the Apex Court with respect to the distinction between skill and chance and affirmed that fantasy gaming does not involve any elements of betting or gambling.

Moreover, the Madras High Court has recognised card games such as rummy and poker to be games of skill owing to the involvement of considerable memory, working out of percentages, the necessity to follow the cards on the table, etc. The Karnataka High Court has also assumed a similar stance by ruling that card games such as rummy, whether played online or physically, would be considered games of skill. The Supreme Court has ordered an ad interim stay of the judgement and order of the Single Judge of the Karnataka High Court which had held, inter alia, that online games played on Gamekraft’s platforms are not taxable as betting or gambling. As the Special Leave Petitions against these High Court orders are currently pending before the Apex Court, the law in this regard remains to be settled.

In the global stage, fantasy sports have been categorised as games of skill rather than that of chance alone. U.S courts have laid down that online fantasy sports are to be considered as games of skill as the participant’s skill in selecting a team influences the winning. Therefore, in light of the aforementioned precedents, the character of online gaming being one of ‘skill’ is well settled and established. Accordingly, the recent decision of the GST council to categorize online gaming as betting and gambling is in direct contravention with national and global precedents.

At this juncture, the legal impact of such a proposal on the taxation sphere must be taken into consideration. The difference between games of skill and chance is a well settled position of law, clarified through six decades of jurisprudence. Therefore, this approach of placing online gaming in the same category as betting or gambling could result in a reopening or reappreciation of cases, and potentially subject the settled jurisprudence relating to the gaming industry to judicial review and scrutiny. However, while the amendment was stated to be clarificatory in nature rather than retrospective per se, press reports indicate that the CBIC has assessed the pending tax liability of online gaming companies since 2017 on the basis of the 28% tax on GGR as compared to the earlier 18% tax. Such reassessments and levy of the new tax rate on past operations would lead to hefty penalties in the form interest for non-payment and could result in unnecessary litigation.

Although clarificatory amendments are generally retrospective in nature, such amendments have been subject to criticism as its retrospective application may lead to issues concerning the rights and duties of parties. The legislature does not intend to attribute retrospectivity to a greater extent than what is expressly mentioned. Therefore, a taxing provision imposing liability is governed by the presumption that it is not retrospective in nature. Recently, the Supreme Court in Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit & Ors. v. Dr. Manu & Anr., established certain principles pertaining to the retrospectivity of clarificatory amendments and held that the retrospective application of the same is only permitted if the pre-amended law is vague or ambiguous. If the clarificatory amendment is a substantive amendment which changes the law, it is to be applied prospectively.

In light of this position of the Apex Court, the assessment of the pending tax liability of online gaming companies in a retrospective manner deserves to be re-examined. This flows from the reasoning that the amendment to increase the tax rate and impose it on the pot value and not merely the GGR has substantially changed the law by imposing new duties on the public rather than merely clarifying the previous law. Additionally, from an economic perspective, if such amendments are to be applied retrospectively, it would pose a striking blow to the entire gaming sector as it would significantly affect the company’s profitability. This particular approach appears counter intuitive at a time when the online gaming industry has exploded in growth and is predicted to become a $5 billion industry by 2025.

ii. Higher Tax levy

As previously stated, the proposed GST regime creates a tax incidence of 28% on the pot value, as opposed to levying an 18% tax on only the GGR. This results in additional tax liability on account of two factors – firstly, the increase in the actual value of tax, i.e., 18% to 28%, and secondly, the taxing of a larger amount, i.e., the pot value as opposed to the GGR. The burden to pay the increased tax would undoubtedly shift to the players because if the platform were to bear the tax liability, the platform fee collected would be less than the GST payable, thus rendering the business unviable. Therefore, such a change in tax regime would place a heavy tax burden upon the players.

iii. Impact on the Overall Industry

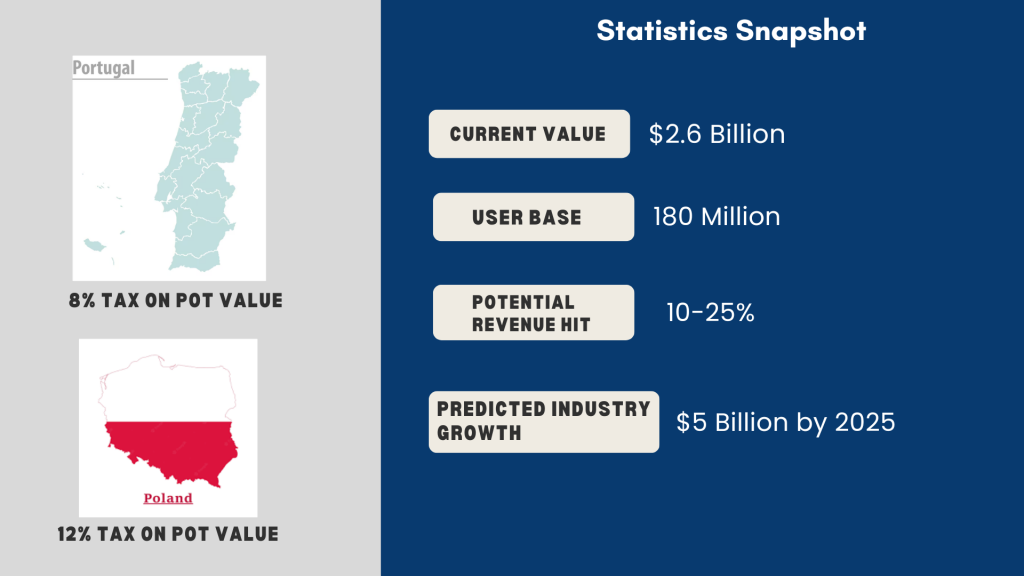

The Indian gaming industry is a rapidly growing market, with a current value of $2.6 billion and it also has the largest fantasy sports market in the world, with a user base of 180 million people. Domestic and foreign investors have invested more than $2.5 billion in the Indian gaming industry, and the industry has produced three unicorns: Dream Sports, Games24x7, and MPL.

However, the recent introduction of a new tax regime for online gaming has the potential to stifle the growth of the industry. This aggressive tax regime could make India less competitive in the global gaming market as gamers may prefer to engage in online gaming services provided by other countries with more favourable regulatory and taxation practices.

This decision can cause a ripple effect in allied sectors such as FinTech (financial technology) and RegTech (Regulatory Technology) services upon which online gaming platforms rely. The former provides services which aid in facilitating the user’s financial transactions and the latter provides services which help in meeting regulatory requirements. The increased tax liability on online gaming services, which is subsequently passed onto users, could result in a dwindling user base. This decline may consequently reduce the clientele for these FinTech and RegTech services, thereby adversely impacting these industries as well. Although it is not yet clear what the exact share of the users in this sector is, experts predict a potential hit of 10% to 25% on revenues. However, the actual impact can be ascertained once the increased tax comes into effect.

Furthermore, the tax levied significantly influences market growth, especially in a sector such as online gaming as the industry operates in a globally competitive market where players can easily shift between gaming operators based upon the lucrativeness of the game. In this regard, a higher tax liability upon the players directly impacts this decision. Based upon a jurisdictional analysis, it is apparent that taxing GGR alone, as opposed to the entire stake, is the standard practice.

At present, various countries such as the UK, US and EU countries levy tax only upon the GGR. France had earlier levied gambling tax on the total turnover or pot value and has now shifted to levying tax only upon GGR after identifying that the previous model has negative consequences such as business shifting to black markets, loss of revenue and non-compliance with the licensing and regulatory system. The Senate also explained that the earlier tax regime was highly burdensome and prevented the balanced development of the market. Therefore, the adoption of such a globally accepted model is more favorable for the industry as it allows for Indian gaming platforms to compete effectively in the global market.

Additionally, at present, various platforms are exploring the idea of relocating to other countries in order to avoid the unfavourable regulatory environment being put in place for online gaming. The new tax levy creates a hostile environment for gaming operators and its enforcement would result in driving companies out of India, owing to the high tax incidence. The level of taxation has an impact on operators who may contemplate applying for a license to operate within the online gaming market.

For instance, Poland and Portugal levy a tax of 12% and 8% on the pot value respectively, which has acted as a barrier in attracting licensed gaming operators and has facilitated offshore betting. In the case of Poland, the increased activity of unlicensed operators has resulted in the gray market taking up almost 60% of the Polish online gaming market. The 12% tax on turnover has often been subject to criticism as it is one of the main reasons why Polish gaming entities have been unable to compete with offshore operators who face relatively fewer fiscal burdens and operate in a more conducive environment. Similarly, the European Gaming & Betting Association has urged Portuguese authorities to review the taxation structure and introduce a taxation upon GGR model as more than 75% of its online gamblers play outside Portugal’s regulated online market. The experiences of these countries indicate that such a model is counterproductive to market growth and maximization. On the other hand, the approach taken by other European markets and the USA demonstrates that tax on the GGR creates a more viable and attractive market and also increases tax revenue. Such a move would reduce offshore gambling while catering to the needs and expectations of both players and operators, which is necessary for sustaining the gaming industry.

iv. Reviewing the Move

The Finance Minister has clarified that a 28% tax on online gaming shall come into effect from October 1, 2023 subject to review six months after its implementation. Therefore, these six months shall reveal the true effect of the high tax incidence on online gaming and if reality unfurls as predicted by experts, the immediate future of the online gaming industry seems bleak. Moreover, regardless of whether a rollback of the 28% tax occurs, this move does not bode well for the industry owing to the fact that unstable policies could act as a deterrent to foreign investments in the gaming sector.

C. THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE MOVE

The inclusion of online gaming and gambling under the same tax bracket implies an equal treatment of entities that are not necessarily similar, and the action may be overlooking the dichotomy between games of skill and games of chance. Treating distinct entities in an equal manner could potentially raise concerns of violating Article 14 of the Constitution, thus rendering the change unconstitutional. The equating of the two kinds of dissimilar games could be classified as arbitrary as it would result in the ignoring of the intelligible differentia between these entities.

It is noteworthy that there have been contentions submitted before the Andhra Pradesh High Court that online card games may not meet the requisite parameters to be considered a game of skill over that of chance. This stems from various reasons such as lack of transparency when the dealer shuffles cards in the online mode and the online mode facilitating greater collusion among players, both of which would expand the scope for the occurrence of manipulation. Moreover, players of physical card games like rummy, would train themselves to the vagaries of the game by noting the cards picked and discarded, whereas players of online card games are offered only a limited amount of time to pick up and discard their cards, failing which their card is automatically discarded. These reasons have also been put forth to support the view that online card games have more to do with chance than skill. Additionally, the “superior knowledge” that the Supreme Court has identified as a prerequisite of games of skill would not be met in the case of online card games as there is no opportunity for players to observe the reactions of the other players in order to assess the flow of the game and make their move accordingly.

However, counter-arguments to the above contentions have been advanced stating that even in the case of online card games, players are required to memorise the cards and hold or discard cards accordingly. With regard to the submission that the online mode may facilitate collusion and manipulation, certain security measures taken on online card gaming platforms were highlighted. These include encryption of details of the playing cards at hand in such a manner that no third-party would be able to access the same and only the player would be privy to his own cards, random seating of players such that players have no control over selection of other players on any table or their position of seating on the table, and disallowing players logged in from the same IP address or located close to each other from being allocated seats at the same table. Furthermore, it was submitted that various platforms do indeed provide adequate time for players to deliberate and discard their cards, so the argument that the lack of time in online card games would result in their classification as games of chance would not hold ground.

D. CONCLUSION

With the rapid growth of the virtual and digital world, it would be prudent to embrace technology in its fullest form. The Indian Government has acknowledged and noted that ‘the gaming market is huge internationally and the number of youth connected to this market globally is increasing.’ If the economy and the gaming industry are to grow to the fullest potential, technology cannot be viewed in isolation. This decision of the GST council has the possibility to render the industry economically unviable. Furthermore, any amendment to the GST law would have to be tested upon the anvil of the Constitution, which in turn would require the settling of the law on whether online card games involve more skill or chance. As a corollary, the question of whether this move would denude the distinction between games of skill and chance will also be addressed. Finally, one must also bear in mind that the proposed uniform tax could disincentivise players from engaging in games of skill, which would be treated the same as games of chance for tax purposes.

Editorial Note: This post was edited by Ishika Garg and Anuraag Bukkapatnam, and the infographics were made by Kshipra Shukla.