In Part 1, we saw the evolution of fiscal federalism from the early British Raj until India’s Independence in 1947. The gradual shift from rigid centralization of fiscal powers towards a more decentralized model was marked by several legislative reforms, a key one being the Government of India Act, 1935 (“GoI Act”). Interpreting the GoI Act, the Federal Court in C.P. Berar firmly acknowledged the federal character and spirit of the GoI Act. Aside from engaging with the nature of fiscal federalism in India, the Court also provided several guiding principles to deal with potential conflicts of legislative competence between the Central and Provincial Levels.

This article seeks to build upon the previous one and explore the evolution of fiscal federalism with the introduction of the Indian Constitution. Aside from providing a brief overview of the Constitutional Framework and the debates around it, this article will also explore the various tests and principles invoked by the Indian Supreme Court in resolving issues of Legislative Competence in the first three decades of our Independence.

A. Fiscal Federalism and the Indian Constitution

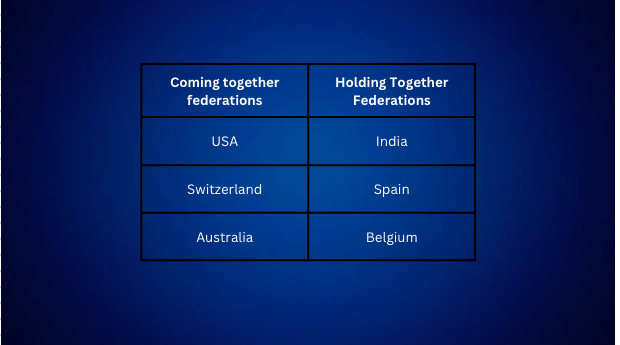

What started as a scheme to imbue financial responsibility in the provinces and reduce the burden of the Centre slowly took the colour of a scheme of fiscal federalism in India. However, as noted by constitutional law scholar Granville Austin in his seminal work ‘The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation’, Indian federalism does not adhere to the “classical” conception of federalism. This classical notion refers to a model where regional governments have sufficient tax bases under their independent control to perform their exclusive executive functions. Unlike the so-called ‘Coming Together’ federation (i.e., Federal Governments wherein several sovereign states come together to form one single entity), none of the provincial governments couched their demands for greater tax bases in terms of protecting their ‘autonomy’, ‘sovereignty’ or ‘state rights’. Austin notes that most members of the Assembly agreed to continue a system where the Centre acted as an agent collecting the most lucrative taxes, which it then assigned or shared with the states.

Rather than viewing India as a ‘classical federal’ model, Austin characterizes the Indian model as a ‘Co-operative Federal’ model. Such a model is characterized by administrative cooperation between a strong Union Government and various Regional Governments. In such a system, the latter depends on payments or grants from the Union Government for its administration. The underlying principle of India’s fiscal federalism is not autonomy but “social revolution”. This underlying principle was acknowledged by the Constituent Assembly as well, in its recognition that poorer provinces would be unable to fulfil their responsibilities without assistance. This principle was also enunciated and opted by the first Finance Commission in 1952, stating that the revenue distribution scheme must work towards reducing inequality among the provinces.

That being said, none of the Union Government leaders wished for a scenario wherein the provinces had to depend entirely on the Union government for their money. As a result, ‘Sales Tax’ (i.e., intra-state supply of goods) along with taxes on Agricultural Income, taxes on Land and Buildings, Alcohol, Opium and certain other minor heads of taxation were left entirely in the domain of the State Government. Among these, Sales Tax constituted the major source of income for the provinces. In a nutshell, the Indian Federal model provides the Centre with a larger share in the lucrative tax bases while also giving it the dominant role in the collection of taxes. While the States receive lesser heads of taxes, they have the exclusive legislative competence to levy taxes on the same. This exclusive legislative competence is similar to the distribution of legislative power in Canada as well (which will be discussed at length in the next article).

While reading the Central and State list, it also becomes essential to look at Article 246 of the Indian Constitution, which reads as follows:

246. Subject-matter of laws made by Parliament and by the Legislatures of States.—

(1) Notwithstanding anything in clauses (2) and (3), Parliament has exclusive power to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in List I in the Seventh Schedule (in this Constitution referred to as the “Union List”).

(2) Notwithstanding anything in clause (3), Parliament, and, subject to clause (1), the Legislature of any State 1*** also, have power to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in List III in the Seventh Schedule (in this Constitution referred to as the “Concurrent List”).

(3) Subject to clauses (1) and (2), the Legislature of any State has exclusive power to make laws for such State or any part thereof with respect to any of the matters enumerated in List II in the Seventh Schedule (in this Constitution referred to as the “State List”).

(4) Parliament has power to make laws with respect to any matter for any part of the territory of India not included 2[in a State] notwithstanding that such matter is a matter enumerated in the State List.

The above Article codifies the division of legislative competence between the Union and State Governments in the three lists. While the Union’s legislation would prevail over the State legislation with respect to items in List 3, no such power exists with respect to matters in List 2. The only circumstances wherein the Parliament could legislate on matters in the State list is when there is either a proclamation of emergency (Article 250) or when the Council of States passes a resolution with 2/3rd strength specifically authorizing the Parliament to legislate on a particular State Item list.

With the constitutional context set, the next segment will explore the earliest invocations of the pith and substance doctrine in resolving disputes of legislative competence.

B. Formalizing the Pith and Substance Test: Bank of Khulna case

The idea of a ‘Pith and Substance’ doctrine was briefly mentioned in the C.P. Berar case. However, the Federal Court did not invoke the same as a test to determine whether the impugned legislation was constitutionally valid. The earliest invocation of the Pith and Substance doctrine as a test for resolving legislative competence conflicts appears to be the case of Prafulla Kumar Mukherjee vs. Bank of Khulna. In that case, the central issue was whether a Provincial Government could indirectly regulate Negotiable Instruments (a Central item list) while legislating on matters dealing with Money Lending (a state item list). The indirect regulation of Negotiable Instruments was done to limit the amount recoverable by such lenders with respect to the concerned instruments.

The Bombay High Court reiterated that in a federal scheme of distributing legislative competence between the various levels of government, overlaps are bound to happen occasionally. In such scenarios, the question to be asked is, ‘What is the pith and substance of the impugned legislation?’. Once such pith and substance is identified, the interpreter would have to examine the List to see where the true character of the impugned legislation can be found. In holding the State legislation to be valid, the Court held that in pith and substance, the legislation in question dealt with Money Lending. Any encroachment upon negotiable instruments was merely incidental to such exercise of power. The Court also held that if such an interpretation was not accepted, several welfare legislations of the State would be stifled at birth because of incidental encroachment onto the Union’s domain.

Ever since the Bank of Khulna case, the Pith and Substance test has been invoked in numerous cases dealing with legislative competence. However, it must be kept in mind that the Pith and Substance test is not a one-stop solution for resolving conflicts of legislative competence between the two levels of government. Rather, the test must be considered part of several foundational principles guiding the interpreter while adjudicating disputes. The next segment elucidates some of these principles.

C. Principles guiding the interpretation of lists

At the outset, it must be noted that Constitutional interpretation cannot be done on the same cannons of Statutory interpretation. As this segment shows, different principles are invoked while interpreting the Lists. Given that there is always a presumption of constitutionality, the rules of interpreting the lists also strive towards upholding the validity of legislations.

Principle 1- Liberal interpretation

In one of the foundational cases for interpreting the lists, the Supreme Court, in the case of Navinchandra Mafatlal vs. Commissioner of Income Tax (“Navinchandra Mafatlal”), observed that, unlike statutory interpretation, Constitutional interpretation could not be done in a ‘narrow’ and ‘pedantic’ sense. These remarks were made in the context of interpreting whether the term ‘Income’, as it appeared in List 1 Entry 82, could also include a ‘Capital Gains’ tax. Holding in the affirmative, the Court laid down the principle that the list entries are not ‘sources of legislative power’. That continues to be the respective Articles within the Constitution. Rather, the lists are merely heads/ fields of legislation.

Therefore, the first principle of interpreting the lists is that of ‘Liberal Interpretation. Words appearing in the List must be given the widest possible construction keeping in mind the ordinary grammatical meaning of the words. Furthermore, general words appearing in the entries would have to be interpreted to include all ancillary/ subsidiary matters with a reasonable connection to exercising such power. In line with this principle, the Supreme Court in the Navinchandra Mafatlal case held that the word ‘Income’ in its broadest sense means ‘anything that comes in’. Consequently, even Capital Gains could be considered as income, notwithstanding the fact that legislative practice up till then did not consider such capital accretions as income.

A caveat, however, is that such an interpretation cannot be stretched to such an extent that it goes beyond the ordinary grammatical meaning of the provisions. As a result, the interpreter would have to perform a balancing act of giving the List entries a liberal interpretation while, at the same time, ensuring that there is a rational nexus between the impugned legislation and the ordinary grammatical meaning of the legislative entry. This principle of liberal interpretation has been reiterated by the apex court in a plethora of subsequent cases as well.

While the Supreme Court in Navinchandra Mafatlal laid down the rule of Liberal Interpretation, the Court in that case was not faced with a clash with respect to whether the Union or the State Government had the legislative competence. The controversy was a standalone one which did not involve the interplay of the various lists. The question, therefore, arises as to how the principle of Liberal Interpretation would operate when, upon giving the list items the widest amplitude, both lists claim legislative competence over a particular item. Invoking Pith and Substance directly could help sort out such a conflict. However, the widest possible interpretation given to list items could result in the interpreter concluding that the impugned legislation’s pith and substance can be traced to both lists equally. It is to resolve such scenarios that before going into the pith and substance of the impugned legislation, the interpreter would first have to attempt to harmonize the concerned entries. This is the second principle, according to which Lists must be interpreted to harmonize the various items contained therein.

Principle 2- Harmonious Interpretation

The principle of harmoniously interpreting the list items forms the bedrock of the Indian cooperative federal model, wherein the States and the Union are expected to cooperate in governance. There are some ways in which such harmonizing of entries may be done. One such method is to limit the scope/ambit of a broader general entry when a more specific entry exists to regulate the same. This flows from a general canon of interpretation wherein the interpreter seeks to ensure that the interpretation of one provision does not render other provisions nugatory. The same also flows from the presumption that the legislator always seeks to avoid tautology and unnecessary words. The Federal Court, in the case of C.P. Berar, had emphasized the need for Harmonious interpretation of the lists as well.

The principle of harmonious interpretation is illustrated in the case of Calcutta Gas Company vs. State of West Bengal, wherein the Supreme Court had to determine whether regulation of Oil and Gas industries would fall under List 2 Entry 24 (dealing with ‘Industries’ in general) or List 2 Entry 25 (dealing with Oil works). While the Court acknowledged that a liberal interpretation of the word ‘Industries’ would include oil industries within its ambit, a specific entry in the form of ‘Oil and Oil works’ indicates that the List considers the same to be a specific and distinct legislative head. As a result, if the general entry of ‘industries’ were interpreted liberally to include ‘oil industries’, Entry 25 would be rendered nugatory. Consequently, the legislative power to regulate oil industries would be traced to Entry 25, not 24.

While Principle 1 and Principle 2 help resolve conflicts between two specific entries, another layer of complexity is added with the inclusion of ‘Residuary’ powers of taxation with the Union Government under List 1 Entry 97.

Principle 3- Residuary powers

A perusal of the Central and State list would provide us with several specific legislative and taxation-related entries. The Central List, however, in addition to containing most of the lucrative tax bases, also includes the ‘Residuary Power of Taxation’. This is embodied in Entry 97 of List 1, which reads

97. Any other matter not enumerated in List II or List III including any tax not mentioned in either of those Lists.

The residuary power is also codified in Article 248 of the Indian Constitution, which gives the Parliament the exclusive power to legislate on any matters not specified in the State and Concurrent List. Including the residuary power adds another layer of complexity to interpreting the entries. In particular, a question that has often been raised before the Supreme Court is the extent to which the Residuary power of the Centre can be invoked to undermine the essence of specific entries in the Union as well as the State List.

The foundational case of the Supreme Court on the interpretation of the Residuary power appears to be Union of India vs. H.S. Dhillon. The Court had to determine the validity of an amendment to the Wealth Tax Act, 1957, which brought ‘Agricultural Land’ within the ambit of an individual’s total assets on which the Wealth tax would be computed. Under the scheme of the Lists, most entries pertaining to Agriculture were in the domain of the State. The state also had the exclusive legislative competence to tax ‘Land and Buildings’ and ‘Agricultural Income’. Entry 86 of the Union List provided the Parliament with the right to tax the Capital value of assets excluding agricultural land. In this context, the Court was called upon to determine whether the Parliament had the legislative competence to bring in such an amendment.

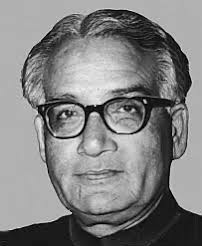

The judgment of the Supreme Court involves several differing opinions. The clash of opinions can be best understood by examining the majority opinion of Chief Justice S.M. Sikri and the dissenting opinion of Justice J.M. Shehlat. For the sake of simplicity, the same is summarized as follows:

Chief Justice S.M. Sikri

Premise 1: It cannot possibly be the intent of the constitutional framers to completely exclude any field of legislation from the purview of legislatures (Central and State) entirely.

Premise 2: Entries in the List are merely legislative heads. They are not the source of power. Thus, the lists cannot be construed to restrict the Union’s legislative authority so long as it complies with the substantive articles.

Premise 3: The Parliament has exclusive powers to legislate on a matter not enumerated in List II and III by Article 248. The wording of the provisions indicates that any matter not covered in List II and List III would fall under the residuary clause. For invoking residuary powers, the Constitution does not state that the field of legislation must not have been covered in any of the specific entries.

Argument 1– Union has Residuary power to legislate on a matter even if it is expressly excluded in a specific entry. The only requirement to be satisfied to invoke residuary power is that the state does not have the power to regulate the same. (becomes premise for next argument).

Premise 4: Union has Residuary power to legislate on a matter even if it is expressly excluded in a specific entry. The only requirement to be satisfied to invoke residuary power is that the state does not have the power to regulate the same

Premise 5: ‘Taxes on Land and Buildings’, as it appears in the State List, is essentially a tax on land and buildings as an individual unit. Any tax on an individual’s cumulative assets cannot be considered as falling under such entry, notwithstanding that such assets include land and buildings.

Premise 6: While sourcing legislative competence, recourse can be taken to more than one entry in the List. The impugned legislation can trace its competence to more than one entry.

Argument 2: As the power to tax the cumulative assets is not traceable to any item in List II, the Union Government can invoke its residuary power to tax the same. It becomes redundant to see if List 1 Entry 86 is the source of legislative power once it is established that the State has no competence to bring about such a tax.

Justice J.M. Shehlat

Premise 1: The objective of residuary powers is to provide the Union government with the power to legislate on matters that could not be foreseen when framing the Constitution.

Premise 2: Residuary powers cannot be invoked to include legislative heads, which are explicitly excluded from the purview of the Union List. Doing so would render such restrictions meaningless.

Argument 1: Resort to residuary powers is only a last resort and cannot be resorted to until all the specific entries in the three lists are exhausted.

Premise 3: There is a difference between the ‘basis’ of a charge and the ‘incidence’ of a charge. While the basis of a wealth tax Act might be the aggregation of the value of assets, the incidence is on the capital value of each individual asset. Therefore, the Wealth Tax can be considered a tax on the capital value of the underlying individual assets.

Premise 4: Upon perusing the distribution scheme of legislative and taxation powers, it becomes clear that the broad head of ‘Agriculture’ was allotted to the State. Keeping this in mind, Entry 49 of List II can be interpreted in a manner so as to include taxes on the capital value of Agricultural Land as well.

Premise 5: The impugned legislation imposes a tax on the capital value of agricultural land, and the same falls within the purview of Entry 49 of List 2.

Argument 2: Keeping in mind the distribution scheme of the Lists with respect to Agricultural Land and the explicit restriction on the Union to tax the capital value of agricultural land under Entry 86, the exclusive power to tax the capital value of agricultural land can be traced solely to Entry 49. Consequently, the Union cannot invoke the residuary power to include agricultural land within the ambit of the Wealth Tax Act.

For C.J. Sikri, the term ‘Taxes on land and buildings’ in its ordinary grammatical sense could not include aggregation of assets. Therefore, this could not be a source for the Wealth Tax Act. However, J. Shehlat preferred a broader interpretation to hold that while the basis of tax is wealth, the incidence is on the capital value of the property. Consequently, the incidence of the Wealth tax is on the ‘Capital value of land and buildings’. Both opinions are classic examples of how the interpreter can arrive at different conclusions while simultaneously adopting the same cannons of interpretation.

In the last post, we saw the gradual shift towards the decentralization of fiscal powers. However, the enactment of the Indian Constitution can be seen as stopping this trend of decentralization. With the Centre receiving a dominant role in this ‘Cooperative federalism’ model, the Courts’ decisions also began to reflect this sentiment. Viewed in this regard, the majority opinion in H.S. Dhillon also appears to be in consonance with the framers’ intent of giving the centre a dominant role. The subsequent articles will further explore the tussle of legislative competence between the Union and the States.

D. References

- Granville Austin: The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a nation

- M.P. Jain: Indian Constitutional Law, 7th Edition.

- Karthik Sundaram: Tax, Constitution and the Supreme Court

- Alice Jacob: Residuary Power and Wealth Tax on Agricultural Property- A note on Union of India vs. H.S. Dhillon