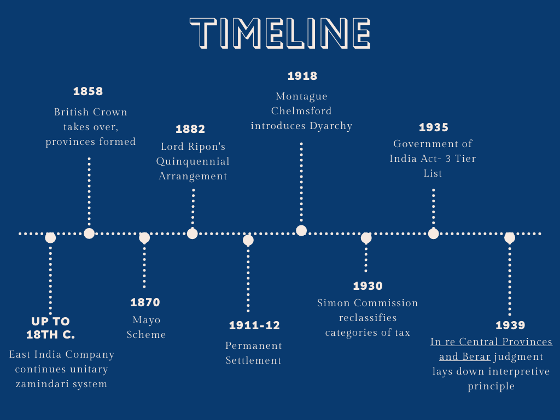

NALSAR Centre for Tax Laws (CTL) is pleased to announce the launch of ‘Simplified’, an explainer series, where we engage with contentious issues of tax law, policy and history. In our first series, we seek to provide an explainer on the issue of ‘Legislative Competence’ and its interplay with the law of taxation in India. Over the course of five blog posts, we will unpack the history of our federal structure (particularly fiscal federalism), explore the various judicial precedents on the tussle of legislative competence between the Union and the states, unpack various tests such as the ‘Pith and Substance’ and the ‘Aspect Theory’, engage with the doctrines invoked by other common law jurisdictions in resolving similar issues, and finally provide an outlook towards the future on this issue in light of the GST. This article deals with the pre-independence context for legislative competence, beginning from the mid-1850s till the framing of our Constitution.

A. Advent of the East India Company and the Centralization of Fiscal Powers

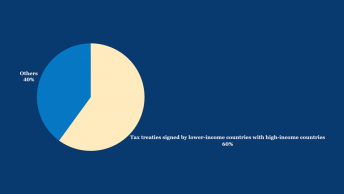

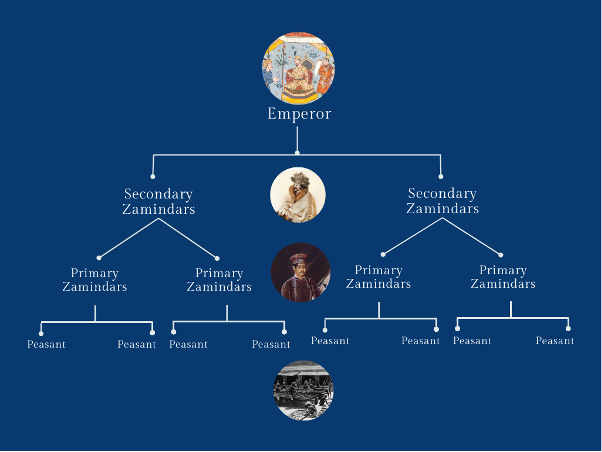

While the history of taxation is as old as civilization itself, this series confines its scope to the developments since the early British Raj. Upon the East India Company’s (‘EIC’) arrival, the taxation system in India was primarily based on the ‘zamindari system’. An artefact of the Mughal Empire, the revenue system in the zamindari system was intricately connected with land rights. The State collected taxes from Zamindars, who possessed proprietary rights over specific portions of land. The Zamindars in turn could collect tax/rents from the peasants who tilled the land. Zamindari rights under the Mughal Empire were initially meant to be given to military personnel in consideration for their services rendered to the crown.

Figure 1: Source

This temporary provision of rights soon turned hereditary, and the revenue collection mechanism gave way to a system similar to a feudal system of property ownership. With the gradual segmentation of zamindari land by means of inheritance and partition, the Zamindars came to comprise two categories- primary and secondary Zamindars. The primary Zamindars were the immediate land owners, who collected rent from the peasants. The secondary Zamindars were more powerful Zamindars, and in turn collected rent from the primary Zamindars. The structure looked as follows:

This was in effect a form of sub-feudalism, as it was increasingly becoming difficult for Zamindars to collect rent from their entire land holding simultaneously. This structure of revenue collection could be categorized as being ‘unitary’ in nature, as there was no concept of any provincial autonomy given to the Zamindars. They were merely ‘collection agents’ in substance. The State also sought to implement various measures to ensure that the Zamindars did not over-exploit the peasants. The centralized form of revenue collection remained undisturbed even with the EIC taking over direct control of Bengal in 1765 following the Battle of Plassey. As the EIC was more a trading concern at its core, it did not wish to make any significant changes to the pre-existing revenue collection mechanism. The Zamindari system continued under the EIC undisturbed. The Company’s primary objective was to bring in place an efficient bureaucracy, judiciary and to regularize the property rights of the Zamindars with respect to their plots of land. This regularization of property rights was done with the proclamation of the ‘Permanent Settlement’ in 1793, under which the Zamindars’ property could be inherited by their successors. However, their land could be confiscated and sold if they failed to pay the pre-determined rent to the Company.

B. Early British Raj and the gradual shift towards decentralization

In terms of the ‘Centralization’ of fiscal powers, there was little change till 1858 when the territories governed by the EIC were taken over directly by the British Crown. For the sake of administrative ease, the Indian territory was divided into several provinces and presidencies. The major presidencies were Bengal, Madras and Bombay, and each of them was headed by a Governor General. Aside from these presidencies, there were several ‘regulation’ and ‘non-regulation’ provinces such as Ajmer, Jhansi, North-East Frontier (Assam), South-West Frontier (Nagpur), North-West frontier (Punjab) and so on. While these provinces were created for administrative ease and possessed a certain amount of legislative power as well, they had no independent authority to raise taxes by themselves. Rather, they resembled collection agents of revenue for the Central Government. The Central Government, in turn, would make discretionary grants to the provinces to help them meet their needs. Such a system, it was noted, did not incentivize the provincial governments to ensure proper collection of taxes (as they did not retain any of the taxes that were raised from their provinces), nor did it incentivize provinces to rein in their expenses (as their focus was instead on demanding as much grants as possible from the Central Government and then spending it in its entirety even without any real need). Taking cognizance of such a system, British legislators were increasingly considering decentralization of fiscal powers by vesting in the provincial governments some limited powers of raising taxes. The first significant step taken in this regard was the resolution issued by Lord Mayo in 1870 (‘Mayo Scheme’).

Figure 2: Lord Mayo- The Fourth Viceroy of India

While continuing the system of fixed grants, the Mayo Scheme devolved certain heads of expenditures and receipts on the local governments, such as police, jails, registration, education, medical services (excluding medical establishments), civil buildings, printings, as well as roads and certain public improvement. This list notably includes many items which continue to remain with the States under List II, Schedule VII of the present Constitution of India. The primary objective of the scheme was to inculcate a sense of fiscal responsibility in the Provincial Governments, and decrease the financial burden on the Central Government. The move towards decentralization was slowly taken forward, with an increasing number of legislative and taxation heads being devolved to the provincial governments.

However, the Mayo Scheme suffered from several drawbacks as well. Firstly, the system of fixed grants from the Central Government continued, and the same was not revised to reflect the yearly price changes. The Scheme did not factor in the inequalities amongst the various provinces while determining the annual fixed grants. Furthermore, the provinces were given fairly minor heads of taxation, with the lucrative head of land revenue continuing to remain with the Central Government. The collection of land revenue continued to be made in the name of the Central Government. The next major step taken towards decentralization of fiscal powers was the ‘Quinquennial Arrangement’ introduced by Lord Ripon (‘Ripon Scheme’). (Often referred to as the father of local self-government in India).

C. Ripon Scheme and the origins of ‘Lists’

In 1882, Lord Ripon revised the Mayo Scheme into a ‘Quinquennial Arrangement’, which formally abolished the system of fixed annual grants to the provinces, and introduced a revenue sharing model between the Central and Provincial Governments. This revenue sharing model created a three list schema for sharing revenue: Imperial, Provincial and Divided. The revenue proceeds from the Imperial and Provincial list items were retained exclusively by the Central and Provincial governments respectively, whereas proceeds from the Divided list were distributed between the Central and Provincial Governments. Although Land Revenue continued to be an Imperial list item, a portion of those proceeds were also made available to the State along with ‘fixed cash assignments’. This marked the shift of provincial governments from absolute dependence on Central Government grants to a gradual ability of raising revenues by themselves for effective administration. The scheme introduced by Lord Ripon can be considered as the origins of the ‘Lists’ under the Indian Constitution as well. A contemporary legislation of this time which envisioned a similar distribution of powers includes the British North America Act, 1867, which provided for a separation of powers between the Federal and Provincial Governments in Canada. However, that is the subject matter of a subsequent post.

The Quinquennial Arrangement was revised in 1887 and 1896, with 1904 seeing notable changes. While the heads remained the same, the share in revenue and expenditures were changed such that those of national importance, like customs and railways, and local importance, like police and education, fell with the Imperial and Provincial Governments, respectively. Provision for lump-sum grants was also made to make good for any shortfalls in revenue. A Royal Commission on Decentralisation was set up in 1908 which among others gave recommendations for the improvement of the financial system in 1909. The report summarised the many problems outlined in previous years such as the rigidity of the scheme and the discrimination among provinces. Crucially, it pointed out the restriction faced by provinces since they could not raise their own taxes or borrow to improve administration. Consequently, the Permanent Settlement was introduced in 1911-12 which devolved forest revenue and expenditure under the complete control provinces. Yet provinces were not given any independent power of taxation. Further, apart from a list of items of national importance, all other matters were devolved to either the Provincial or Divided List.

It was the Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919 which finally ushered in several substantial changes. The Montague Chelmsford Report of 1918 had recommended doing away with the ‘Divided’ List by giving the provinces residuary powers of taxation. As the Central Government would now have a deficit, the provinces would have to make fixed contributions to the Central Government. Accepting the recommendations, the Parliament passed the Government of India Act, 1919, thereby formally abolishing the ‘Divided head’ of taxation. The taxation powers of the Central and Provincial governments were now mutually exclusive. Furthermore, the reforms introduced a system of ‘Dyarchy’ within provincial governments. Subjects within the domain of Provincial Governments were assigned to either ‘Reserved’ or ‘Transferred’ categories. While the former were regulated by executive appointees of the British Crown, the latter consisted of individuals elected within the provincial governments. Consequently, there was a significant overhaul of the list system, which included handing over land revenue, irrigation, excise, forests, and judicial stamps into the complete providence of the provinces as “Transferred” subjects. Furthermore, Provincial Governments were allowed to borrow, approach the money market and draft their own budgets in an effort to make them more independent.

D. Government of India Act, 1935

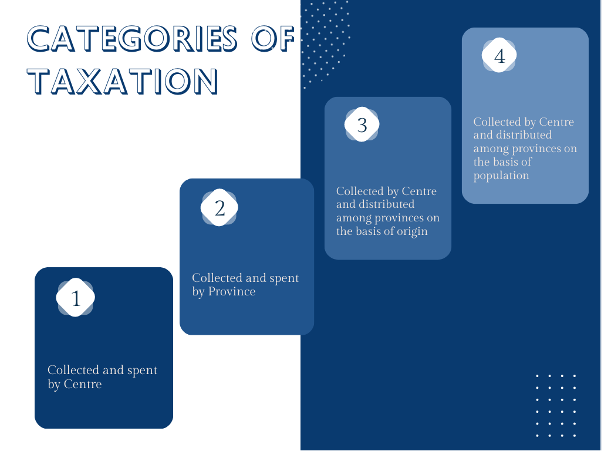

The 1930s witnessed the formation of numerous committees which recommended further devolution. The Simon Commission, appointed in 1927, recommended the abolition of the Dyarchy system of designating subjects as either ‘Reserved’ or ‘Transferred’. Furthermore, the Commission recommended a re-categorization of taxation heads under 4 categories, which are as follows:

The recommendations of the Simon Commission were the subject matter of discussion in the first round table conference held in 1930. Pursuant to this conference, another committee headed by Viscount Peel was set up, which recommended transferring the entire Income Tax revenue to Provinces. A subsequent committee headed by Peel also opined that permanent provisions must be added to provide a share for the provinces. A White Paper on Indian Constitutional Reforms likewise suggested a fixed share of Income Tax should be shared with provinces, which the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms, 1934 suggested should not exceed 50%. The several committee reports from this period mainly deal with the issue of how various heads of taxation would be distributed between the Central and Provincial Governments, and on what basis would the Central Government devolve funds to the Provincial Governments.

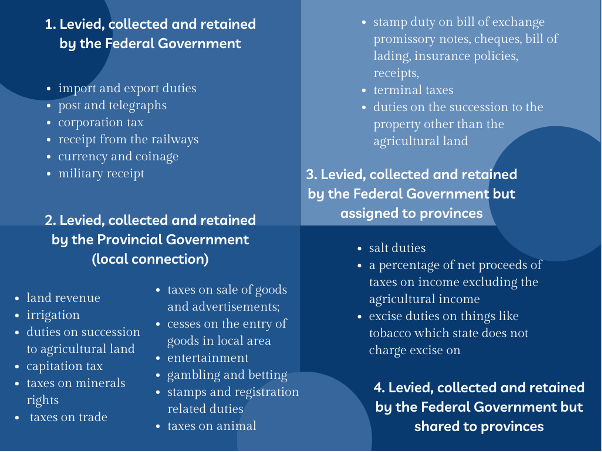

All of these recommendations culminated into law in the Government of India Act 1935 (“GoI Act”), which set out the skeleton for the Seventh Schedule of our present Constitution, with a Federal, Provincial and Concurrent list of items. The Act prescribed four classes of taxes: (1) levied, collected and retained by the Federal Government, (2) levied, collected and retained by the Provincial Governments, (3) levied and collected by the Federal government but assigned to the Provinces and finally, (4) levied and collected by the Federal government but shared with the Provinces.

Additionally provisions were made for grants-in aid and borrowings. Further an enquiry committee set up under Sir Otto Niemeyer clarified that the extent of share in income tax, exclusive of corporate tax, assigned to provinces would not exceed 50% of the net proceeds, along with recommendations for grants-in-aid and reduction of debts. The Constituent Assembly largely adopted the GoI Model with minor changes such as changing ratio of assignment of income tax between the Centre and States (erstwhile Part-A States) to 40:60, assignment of certain excises to the states, and formation of a Finance Commission to deal with matters of the sharing of revenue.

The GoI Act departed from the erstwhile federal structure by detaching the revenues and accounts of the Provincial Governments from that of the Government of India. As a result, the Provincial Governments enjoyed greater flexibility in their ability to determine their budgets. Furthermore, the GoI Act sought to minimize the overlapping of revenue heads between the Central and Provincial lists. That being said, the distribution of revenue heads still favoured a unitary form of governance. Major heads of income such as the Income Tax and Corporation Tax were allotted to the Central Government. The revenue generated by the provincial governments was not sufficient for taking up developmental programmes, and was barely sufficient to meet their operational and day to day administrative needs. As a result, provinces continued to be dependent on grants in aid from the Central Government for developmental activities.

E. Legislative Competence and the origins of a Central-Provincial clash

Although the Lists as formulated in the GOI, 1935 attempted to prevent overlap, it could not foreclose the possibility in its entirety. One of the first cases that dealt with this possible conflict between a taxing act encroaching into the list of another government was seen In Re Central Provinces and Berar Sales of Motor, Spirit and Lubricants Taxation Act (“C.P. Berar”). Under Section 100(1) of the GoI Act, the Federal Government had the exclusive power to legislate over matters in the Federal List notwithstanding the powers conferred on the Provincial Government (a non-obstante formulation that continues to do this day in Article 246). Item 48 in the Provincial List prescribes the power to legislate a “tax for the sale of goods”. On this basis, the provinces of Berar and Central Provinces imposed taxes on the sale of motor spirits and lubricants manufactured in India. However, it was contended that this was in excess of their competence and in encroachment of Item 45 of the Federal List which provided for excise on “goods manufactured or produced in India”.

The technical issue before the Federal Court was whether the taxable event in question was a ‘Sale of goods’, or was it an excise duty on the ‘Manufacture’ of goods, albeit collected at a later point of time. While the Court’s views on taxable events and the interpretation of the term ‘Excise’ is a landmark in its own right, this article engages more with how the Federal Court envisioned the federal structure of the Indian Constitution along with its views on how such disputes should be settled.

The Federal Government argued that Entry 48 must be read as “tax for the sale of goods” excluding taxes or duties that fall under the Federal List. Meanwhile, Sir Alladi Krishnaswami Iyer as Advocate-General for the Province of Madras drew on the historical argument for why the two Lists must be read in a way that did not render the item in the Provincial List nugatory. For this, he noted how in moving from a Unitary to a Federal system of government and allowing for the provinces to be autonomous, it was intended that they be given sufficient financial resources. Therefore, the inclusion of sales tax should be read in furtherance of this intention. Upon considering the rival submissions, the Federal Court led by Chief Justice Maurice Gwyer laid down several foundational principles, which continue to be relevant in terms of understanding the federal structure of the Indian Constitution.

Figure 3: Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer

Figure 4: Chief Justice Maurice Gwyer

At the outset, the Court noted that no reliance could be placed by either sides on the legislative practice in India prior to 1935, as the GoI Act marks a fundamental shift from the erstwhile forms of practice. On the issue of method of interpretation, the Court noted that Constitutional documents could not be interpreted in a ‘narrow’ or ‘pedantic’ sense, but rather in a ‘broad’ and ‘liberal’ spirit keeping in mind that large powers could be conferred in very few words as well. With regard to the ‘legislative object’ of the GoI Act and the lists, the Court unequivocally states that the objective was to grant ‘Provincial Autonomy’. Therefore, this objective must guide the court in its interpretative exercise.

“In a federal Constitution like that embodied in the Constitution Act, the Provincial and Federal Governments are co-ordinate Governments. The Legislative sphere assigned to each is exclusive. Subject to any restrictions imposed in the Act itself, they have as ample and extensive an authority as the Imperial parliament itself”

“The correct approach to interpretation of S. 100 of the Constitution Act and the Legislative Lists thereunder is that laid down in analogous conditions in the interpretation of ss. 91 and 92 of the British North America Act by the Judicial Committee. In spite of the dominance assigned to the Federal Legislature, the Court should endeavour to resolve the apparent conflicts that may arise between the federal and provincial legislative powers and give effect to the powers of both”

Taking note of the fiscal powers distributed between the Federal and State Government, the Court notes that the distribution largely favours the Federal Government. After recognizing the fact that newly emerging autonomous Provinces would need adequate financial resources to exist and thrive, the Court notes that the intent of the Parliament was always to try and provide Provinces with newer forms of revenue generation.

Building upon the legislative intent behind the GoI Act, the Court held that in the federal structure of the GoI Act, the Provincial and Federal Governments were ‘co-ordinate’ governments. This meant that with respect to matters in the Provincial List, the Provincial legislatures had as much authority as the Imperial Parliament itself. In this regard, the Provincial Legislature could not be considered as inferior to the Federal Government. Both these coordinate governments had mutually exclusive domains of governance and taxation. As the Federal and Provincial Governments’ power of taxation could not have been intended to be in conflict with each other, they must be read harmoniously to give equal effect to both. For this, the principle that the ‘general ought not to subsume the particular’ was applied. Although he prefaces that it would be wrong to consider the Federal to be “general” and the Provincial to be “specific”, the former in essence cannot be used to render the latter a nullity, which would have been the consequence of the interpretation pressed by the Federal Government.

Continuing with this line of thought, Sulaiman J., in his concurring opinion, reiterates how in aiming to avoid overlap, an undefined term, “excise” in the present case, could not be interpreted in a way to subsume a particular term, i.e, “sales”. In giving his opinion, Justice Sulaiman expressly notes that several English precedents submitted by the Federal Government could not be relied upon, as the English Constitution was not a Federal one whereas the GoI Act was Federal in its essence. Towards the end of his opinion, Justice Sulaiman states that when interpreting the lists, one would have to look at the “Pith and Substance” of the Act in question to determine whether the legislation in question encroaches onto the domain of the other.

Giving his concurring view, Jayakar J. states that although the Federal Legislature is given pre-eminence in Indian Federal structure, it cannot be said that the Parliament intended that the powers ‘exclusively’ granted to the Provincial Governments could be absorbed by the Central Legislature in case of a conflict.

In conclusion, the Federal Court unanimously held that the legislations introduced by the Provincial Legislations were constitutionally valid. The gradual devolution of fiscal powers which began with the Mayo Scheme all the way till the GoI Act now received Judicial approval as well. Despite British Raj beginning with absolute centralization of authority, the GoI Act firmly established the nature of the Indian Constitution as being a fundamentally ‘Federal Document’.

F. Conclusion

This blog post largely confined itself to the gradual evolution of the federal structure in pre-Independence India. This post largely serves as a context for the next post, which will deal with the enactment of the Indian Constitution and how the Supreme Court of India responds to early controversies dealing with the interplay of the Union and State list. In particular, the subsequent blog post would also look at how the ‘Pith and Substance’ test (which was briefly introduced in the Berar case) is subsequently applied by the Indian Supreme Court.

G. Bibliography

- Rekha Bandhopadyay, Land System in India: A Historical Review, 28 Economic & Political Weekly 49 (1993).

- Dr. Hareet Kumar Meena, Land Tenure Systems in the Late 18th and 19th century in Colonial India, American International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences.

- Anand V. Swamy, Land and law in Colonial India, in Law and Long-Term Economic Change: A Eurasian Perspective 138 (Debin Ma & Jan Zanden, eds 2011).

- Rajesh Kumar, Evolution of Fiscal Federalism in the Colonized India, Perspectives on Federalism, Vo1. 11, issue 1, 2019.