Over the course of the last four articles, we explored the various tests and principles invoked by the Courts while adjudicating on legislative competence issues. While several such tests and principles exist, the primary reason why such principles are required in the first place is because of the constitutional scheme of distributing legislative powers. The Canadian and Indian constitutions provide for an exclusive separation of legislative power. While India has a concurrent list, all taxation-related entries fall either in the Union or the State list. As a result, it becomes necessary to evolve with principles that help source an impugned legislation’s legislative competence to a single list. That said, if the power to impose taxes is not considered an ‘exclusive’ power, several principles for sourcing legislative competence become redundant. This is precisely the situation that we currently see with the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). This concluding article explores the GST along with its impact on fiscal federalism, particularly in the context of legislative competence to impose taxes.

A. Overview of the GST Constitutional Framework

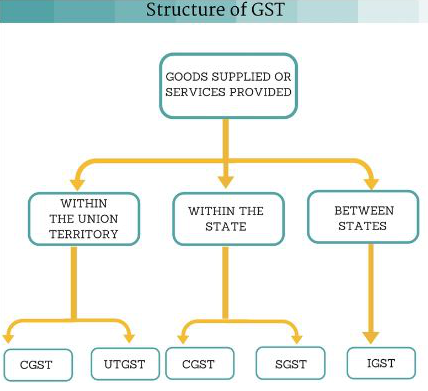

The GST was introduced with the 101st Constitutional Amendment Act, with the intention of creating a ‘One nation one tax’. Several different central and state levies such as sales tax, services tax, excise, VAT, etc. were abolished and replaced with a single GST. While the erstwhile system consisted of several different taxes with different taxable events, GST is payable solely on the ‘supply’ of goods and services. Aside from reducing the complexity of dealing with several legislations, the GST regime also benefits the end consumers by doing away with a cascading effect of taxes. While intra-state supplies are chargeable to a CGST and SGST, inter-state supplies are chargeable to IGST which is then distributed between the center and states based on a pre-determined formula.

Prior to the GST, the power to levy sales tax was with the States. Bringing about the GST, therefore, necessitated a Constitutional Amendment, which would have to be ratified by at least 50% of the State legislatures. With the coming into force of the GST, several taxation entries were deleted from List II of the Seventh Schedule. In its place, several new articles were inserted into the Constitution for the purposes of GST. The power to levy a GST on intra-state supplies and inter-state supplies can be traced to the newly Article 246A(1) and 246A(2) of the Constitution respectively. While Article 246A(1) gives the Parliament and State legislature the legislative competence to impose a GST, Article 246A(2) gives the Parliament ‘exclusive’ power to impose GST on inter-state supplies. Aside from this, Article 279A of the Constitution sets up a GST council. Aside from providing the composition of the council and its procedure of functioning, the Article also prescribes the various issues on which the GST council can ‘make recommendations’ to the Union and the States. The relevant extracts of both articles can be seen below:

246A. Special provision with respect to goods and services tax.—(1) Notwithstanding anything contained in articles 246 and 254, Parliament, and, subject to clause (2), the Legislature of every State, have power to make laws with respect to goods and services tax imposed by the Union or by such State.

(2) Parliament has exclusive power to make laws with respect to goods and services tax where the supply of goods, or of services, or both takes place in the course of inter-State trade or commerce.

(4) The Goods and Services Tax Council shall make recommendations to the Union and the States on—

(a) the taxes, cesses and surcharges levied by the Centre, the States and the local bodies which may be subsumed in the goods and services tax;

(b) the goods and services that may be subjected to or exempted from the goods and services tax;

(c) the threshold limit of turnover below which goods and services tax may be exempted;

(d) the rates of goods and services tax; and

(e) any other matter relating to the goods and services tax, as the Council may decide.

(5) While discharging the functions conferred by this article, the Goods and Services Tax Council shall be guided by the need for a harmonised structure of goods and services tax and for the development of a harmonized national market for goods and services.

The aforementioned provisions raise a question: If the GST Council recommends GST be levied on a particular rate, can the State legislature choose to impose their state GST in a different manner? The confusion primarily arises given the wording of Article 246A. While the Parliament has ‘exclusive’ power to impose inter-state GST, no such exclusivity is mentioned in 246A(1). Moreover, the repugnancy related Articles are specifically not made applicable to Article 246A by virtue of the notwithstanding clause. The Supreme Court was called upon to determine these issues in the case of Union of India vs. Mohit Minerals, which will be discussed below.

B. Supreme Court and the Mohit Minerals case

The decision in Union of India vs. Mohit Minerals (‘Mohit Minerals’)primarily dealt with the validity of certain ocean freight charges. However, one of the several issues before the Court was whether the recommendations of the GST council were binding on the Parliament and the State legislatures. The Union Government submitted that the recommendations of the GST Council were binding on both. The argument was made on the basis of the overall structure of the GST, which stresses on harmonization of taxes. As GST Council was a converging point of decision-making for the Union and the States, the Union asserted that the council’s decisions must be deemed to be binding according to the principles of cooperative federalism.

On similar lines, Mr. Alok Prasanna Kumar from Vidhi has also written about how the term ‘recommendations’, as it appears in Article 279A, must be considered binding. He provides two reasons in support of the same: Firstly, the entire structure of the GST would collapse if each State had the power to impose its own GST. There would be no uniformity in taxation or the rules governing GST. Secondly, Article 279A(11) provides for the setting up of a dispute resolution mechanism by the GST council. Such disputes could be between the states or between the union and the state(s). If there were no binding legal obligations arising from the recommendations, such dispute resolution clauses would be redundant. Therefore, we must read the term ‘recommendations’ contextually, and consider the same to be ‘binding’.

While the Court cited and acknowledged the scholarship of Mr. Kumar, it ultimately held that the decisions of the GST council are merely recommendatory and not binding on the Parliament or the State legislatures. Upon a strict interpretation of Article 246A, the Court held that the same amounted to a ‘simultaneous’ power to legislate. This is distinct from the concurrent power to legislate, as such concurrence only arises when a particular field of legislation is specifically included in the Concurrent list of the Seventh schedule. The power to impose GST is not traced to any entry in the List. Rather, its source arises from Article 246A directly. Therefore, the provisions of repugnancy under Article 254 would not be applicable.

The Court also addresses the arguments pertaining to Article 279A, which provides for dispute resolution. Mr. Kumar’s arguments were premised on the idea that the dispute resolution mechanism that is envisaged under Article 279A(11) is for disputes arising from the recommendations of the GST council. The Court however goes into the legislative history of the provision and notes that the Parliament specifically deleted an extract from this Article which stated that the adjudicating body would deal with ‘disputes arising out of the deviation from the recommendation’. The Court also notes that the decision-making power in the GST Council is based on majority and not unanimity. As a result, the Council’s decisions can serve as an avenue for political contestation across party lines.

The Court also addressed the Union’s arguments about the consequences of such a decision on the ‘cooperative federal’ model of India. To this, the Court stresses how the functioning of federalism need not always be collaborative. The Constitutional design provides States with a certain amount of freedom for political contestation as well. In the words of the Court, ‘Harmonized decision making thrives not just on cooperation, but also contestation’. Terming this as ‘un-cooperative federalism’, the Court views the independence given to States in accepting the recommendations as a ‘fine balance’ for Indian federalism. In the absence of any provision deeming GST council decisions to have the force of law, it cannot be said that the same are binding on the Union or the States.

C. The future of legislative competence conflicts

We began this series by examining the colonial-era developments with respect to fiscal federalism. We noted how India began with a centralized model, where fiscal powers were gradually devolved to the provinces. With the coming into force of the Indian Constitution, we saw a reversal of this trend. Gradually the Union began playing a greater role in the imposition and collection of taxes. The use of the residuary powers of taxation coupled with the invocation of the ‘Aspect theory’ also gave the Union considerable leeway to transgress into the State’s exclusive ability to impose taxes as well.

The judgment in Mohit Minerals does give the States considerable freedom in imposing GST and tailoring it specifically to their needs. It is among the rare instances where Courts have stressed the importance of dissent and conflict in a federal scheme of governance. This is in stark contrast to most of the cases (whether Indian or Canadian), where Courts have time and again emphasized the need for cooperative federalism. That being said, it cannot be disputed that the Central Government continues to play an increasingly dominant role in the field of taxation, whether direct or indirect. Although one cannot discern any linear developments in this regard, by and large India has moved towards a more unitary model in fiscal matters.

Impact on fiscal federalism aside, the judgment in Mohit Minerals does make several principles for determining legislative competence largely irrelevant in the context of taxation. The exclusive nature of distributing legislative power, which underlies our original constitutional framework, no longer applies in the context of GST. With both the Centre and State having simultaneous power of legislation, the principle of repugnancy would not be attracted even in case of a direct conflict between the two. As the Union has the power to impose GST as well as Income Tax (the two largest sources of tax in the country), there remain no major exclusive tax bases for the State legislatures under List 2. Any further incursions into their taxation fields, therefore, seem unlikely. Nevertheless, the Pith and Substance test, Aspects doctrine, and several other principles of interpreting the list continue to be a part of our Constitutional Jurisprudence, and it remains to be seen how the various stakeholders shape the fiscal federal structure in the years to come.

(This explainer series was prepared by Aditya Raj, Anuraag Bukkapatnam, Archita Satish, Ishika Garg, and Pratham Shah)