In the previous post, we engaged with the ‘Pith and Substance’ doctrine in Common Law. In particular, we explored its origins in Canadian judicial precedents and how those precedents influenced the Constitutional design of Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Australia. We also explored the origins of the ‘Aspect theory’ in resolving legislative competence disputes in Canada and Australia. In this post, we will explore the manner in which Indian courts have invoked the double aspect theory to resolve legislative competence disputes under the Seventh Schedule. Furthermore, we would also engage with the views presented by various scholars on the manner in which the aspects doctrine has been invoked in India.

A. The Federation Case and its Legacy

The Government of India enacted the Expenditure Tax Act, 1987, which imposed a tax on the expenditure incurred by a particular class of hotels (hotels whose per-room charge exceeded INR 400 per day per individual). The constitutional validity of the same was challenged before the Supreme Court in the Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Association vs. Union of India (‘Federation case’). The Petitioners, led by Senior Advocate Nani Palkhivala, submitted that the Parliament lacked the legislative competence to enact such a law. By its very nature, the class of hotels that the legislation targets are high-class hotels which provide luxurious accommodation services to their patrons. Urging the Court to disregard the nomenclature of the tax, the petitioners argued that the tax was effectively on the provision of ‘Luxury’, which is an item in the State list.

On the other hand, Attorney General K. Parasaran submitted that the legislation in question did not fall under List II, as the expenditure tax in Pith and Substance could not be considered to fall under the item ‘Luxuries’ at all. Furthermore, the Attorney General submitted that the division of legislative powers specifically recognized the demarcation of ‘distinct aspects’ of the same matter as ‘distinct topics of legislation’. Therefore, legislating on the ‘expenditure aspect’ of luxury would constitute a separate legislative head from luxury itself.

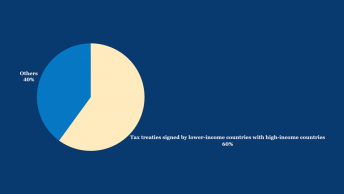

Accepting the arguments of the Union, the Supreme Court stressed the need to interpret the list entries harmoniously. Quoting from Lefroy’s ‘Canadian Federal System’, the Supreme Court noted the possibility of the same transaction involving two or more taxable events in its different aspects. It did not matter, therefore, that the Expenditure tax imposed was specifically on the provision of Luxury services as opposed to a general Expenditure tax. Although the tax was related to ‘Luxury’, it was imposed on the ‘Expenditure aspect’ of Luxury. The same can therefore be justified by invoking the Union’s residuary powers under Entry 97 of List 1.

The ratio in the Federation case has subsequently been cited in several other conflicts of legislative competence as well. Among the prime examples include the case of All India Federation of Tax Practitioners vs. Union of India (‘Service Tax case’). The case involved challenges to the validity of Service Tax imposed on professionals such as Chartered Accountants. The Petitioners argued that the State Government has the exclusive legislative competence to impose a tax on ‘Professions, Trades, Callings and Employment’ under List II Item 60. The Supreme Court, however, upheld the validity of service tax by invoking the Aspects doctrine. While List II item 60 contemplates a tax on the ‘Status aspect’ of being a professional, the Supreme Court held that the Service tax is a tax on the ‘Service aspect’ of being a professional. This is similar to the analogy provided by the Australian High Court in the Fontana Films case (discussed in Part 3), where it held that every legislation has at least two aspects: firstly, the activity being regulated and secondly, the entity performing the activity being regulated. While the Supreme Court did not cite the Australian precedent, it nevertheless held the Service tax on Professionals valid on similar lines.

The above two cases involve the invocation of the aspects doctrine to support a Union legislation. However, the doctrine has been invoked to support State legislations as well, as can be seen in the case of Goodricke Group vs. State of West Bengal (‘Goodricke Group case’). The State of West Bengal had introduced two cesses, with the objective of supporting primary education and rural employment, respectively. Under such Act, a cess was imposed on land and buildings in the State at a rate of 6 paise on each rupee of development value. However, a different measure was adopted with respect to Tea Estates. The cess on Tea estates was calculated based on the amount of tea produced at such Tea Estates. The Petitioners argued that by basing the tax on the production of tea leaves in the Estate, the tax in question ceases to be a tax on the Capital value of Land and Buildings. Consequently, the State could not resort to List II Item 49 as no direct connection existed between the land and the tax. According to the Petitioners, the correct characterization of the levy would be an ‘Excise Tax’, which can be traced to List 1 Entry 84.

However, the Court rejected the Petitioners’ arguments by holding that a tax on land and buildings is essentially a tax imposed with reference to its yield. As a result, it is possible for a tax to continue being a tax on land and building, notwithstanding the fact that the measure is linked to the income-yielding capacity of the land. In reaching this conclusion, the Court also invoked the Federation case. It endorsed the idea that a single transaction could have two or more taxable events, each of which could constitute separate legislative heads. However, the Court stops short of explicitly stating that the impugned legislation taxes the ‘Land and Buildings’ aspect of the Tea Estates.

That being said, the Aspect theory has also been subject to several criticisms. The next segment deals with the same.

B. Critique of the Aspect Doctrine

In the previous post, we saw the apprehensions of the Canadian Supreme Court regarding the indiscriminate invocation of the Aspects doctrine. The Court’s primary concern was the dilution of the federal scheme in Canada wherein the Federal legislature and the Provinces were given exclusive powers of legislation. On similar lines, the manner in which the Aspects doctrine has been invoked in India has also been subject to criticism. On the one hand, it is argued that the Aspects Doctrine is unique to the Canadian Constitutional scheme and should not be transplanted to India. On the other hand, it is argued that there is no difference between the Aspects Doctrine and the Pith and Substance Doctrine functionally. This segment engages with both these criticisms.

I. A Canadian Tree on Indian Soil- Relevance of Aspects Doctrine in India

In a lecture titled “The Constitution, Federalism and GST” delivered at NALSAR, Senior Advocate Arvind P. Datar argued that the Aspect theory originated in Canada due to its unique Constitutional structure and has been wrongly invoked in Indian Constitutional Law. In our previous post, we provided various similarities and distinctions between the Canadian and Indian lists. While both lists envision an exclusive division of powers, the Canadian List differs from the Indian List in two crucial ways: firstly, the entries in the Canadian List are fewer in number and worded in a very open-ended manner, and secondly, the Canadian lists do not have any concurrent list like India. As we’d seen earlier, the distribution of taxation powers in Canada is based on a distinction of ‘Direct vs. Indirect’ taxes, whereas India has a much more detailed distribution of taxation powers. Consequently, overlaps of legislative fields were much more likely in the Canadian Constitution. In order to harmoniously interpret the Canadian Constitution, it would become necessary to recognize the possibility of a particular legislation drawing its source equally to both lists (as seen in the Drunken Driving illustration in the previous post).

After distinguishing the Canadian Constitutional structure from the Indian Constitution, Mr. Datar recounts how he lost several cases (including the abovementioned Service Tax case before the Bombay High Court) due to an incorrect invocation of the Aspects doctrine. According to him, whenever there is an overlapping tax on an ambiguous subject, the first step would be establishing legislative competency through the doctrine of pith and substance. If legislative competency is established, the next step would be to apply the doctrine of repugnancy under Article 254 if any entry is contrary to another one. However, if aspects doctrine is being applied, then the Courts tend to only look at the two distinct aspects of a subject and hold it valid without referring to the doctrine of repugnancy. The abovementioned cases also focus only on the distinct aspects without understanding its consequences, as one can always view a tax from different angles and hold it valid. Moreover, invocation of the Aspects theory flies right in the face of a fundamental canon of interpretation, which is to give the List entries a liberal interpretation. When faced with the issue of service tax on professionals, Mr. Datar submits that the answer should be in the affirmative. Subsequently, the State alone has the right to tax such activities, and the Union should not be able to tax the same by claiming the existence of another aspect of the transaction. This approach was stressed upon by Justice Chinnappa Reddy in the International Tourist Case as well but was not followed in the Service Tax Case.

“Upon giving a wide/ liberal interpretation to the item “Taxes on professions, trade, callings and employment”, can services provided by such professionals be included within the ambit of this entry of List II?”

In many ways, Mr. Datar echoes the minority view in HS Dhillon, where Justice Shehlat stressed the difference between the Canadian ‘interlacing’ model and the Indian ‘disjunctive’ model. In fact, the Supreme Court has, in some cases, exercised caution and refused to invoke the Aspect theory. One such instance includes the case of BSNL vs. Union of India (‘BSNL’). With the introduction of the Service Tax, the Union imposed a service tax on the provision of sim card services. However, the sale of the physical sim card was subject to sales tax, which fell under the State’s domain. The State sought to tax the value of services offered by the Sim Card provider by invoking the Aspects doctrine. They contended that what constituted services in one aspect could be considered a sale in another aspect, thereby bringing in two aspects in a single transaction. While the Supreme Court did not question the validity of the aspects doctrine, it clarified that the Aspects doctrine could be invoked only when there is an overlapping of legislative entries and not to examine the factual reality of the transaction. The Supreme Court’s refusal to invoke the aspects doctrine in cases of Service vs. Sales Tax can also be seen in the case of Imagic Creative vs. Commissioner of Commercial Tax, which dealt with an advertising agency providing advertising material (i.e., design brochures, annual reports, etc.) to their clients. Once again, the Court refused to view the factum of the transaction (provision of the material) as having both a sale as well as a service aspect.

I. View 2- Aspects Doctrine does not exist

View 1 considered the Aspects Doctrine to be wrongly transplanted into Indian jurisprudence. View 2, on the other hand, questions the very existence of the Aspects doctrine itself. Under this view, the Double Aspects theory is just another term used for the Pith and Substance test. V. Niranjan, in his chapter on Legislative Competence in the Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution, points out the similarities between the Pith and Substance test and the Aspects doctrine. He relies on three indications to support his view that the aspect theory is the same as the Pith and Substance test.

First, the reliance on the “true nature and character” of the subject tax, which is an essential component of the Double Aspect test, is identical to the pith and substance analysis as well. The judges have often reasoned that a transaction may involve two different aspects and that the overlapping does not detract from the distinctiveness of the aspects. The doctrine of pith and substance also states that if a subject might incidentally ‘affect’ another issue in some way, it is not the same thing as the law being on the latter subject. Second, the authorities that the Federation case cite are, in fact, demonstrating the rule of pith and substance, such as Hodge vs The Queen. It uses the same language which is used for pith and substance, only with a different nomenclature called ‘aspect’ of the legislative entry. It is the same principle which is in play in all these jurisdictions. Even the Federation case, seen as the landmark case on the Double Aspect theory, does not exactly distinguish between the Aspects doctrine and the Pith and Substance doctrine. In reaching its conclusion, the Court in federation invokes the Pith and Substance doctrine as well. Viewed from another lens, one could argue that the Expenditure Tax was not, in pith and substance, derived from the item titled ‘Luxury’ in List II. When articulated this way, the Pith and Substance test would give the same result as the Aspects doctrine.

Justice Rohinton Nariman also endorses this view in a lecture, where he argued that the Courts have not properly understood the Aspect theory. Citing the federation case, Justice Nariman argues that the Aspect theory could only be invoked in case of competing entries (i.e., in case of a conflict between two specific entries in List 1 and 2). Therefore, it has no applicability in cases where taxes are sought to be legitimized by having recourse to the residuary entry.

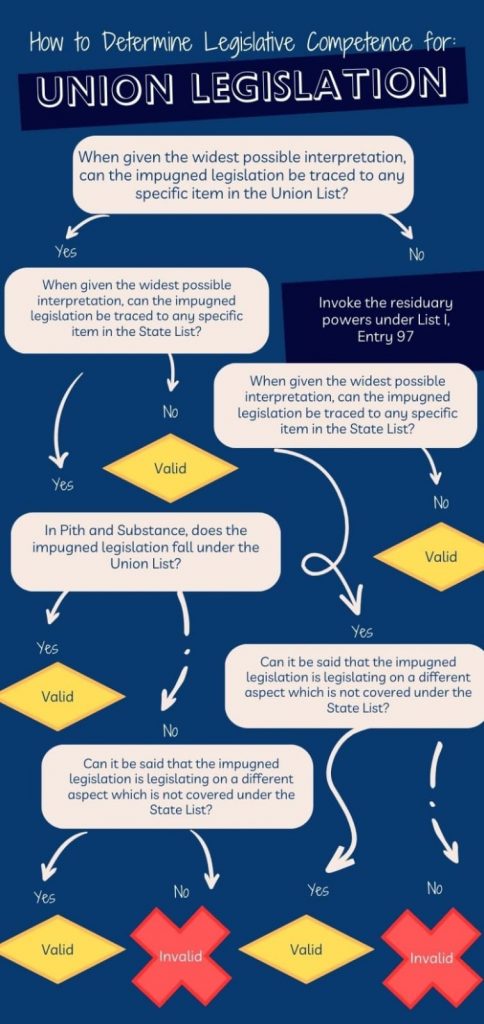

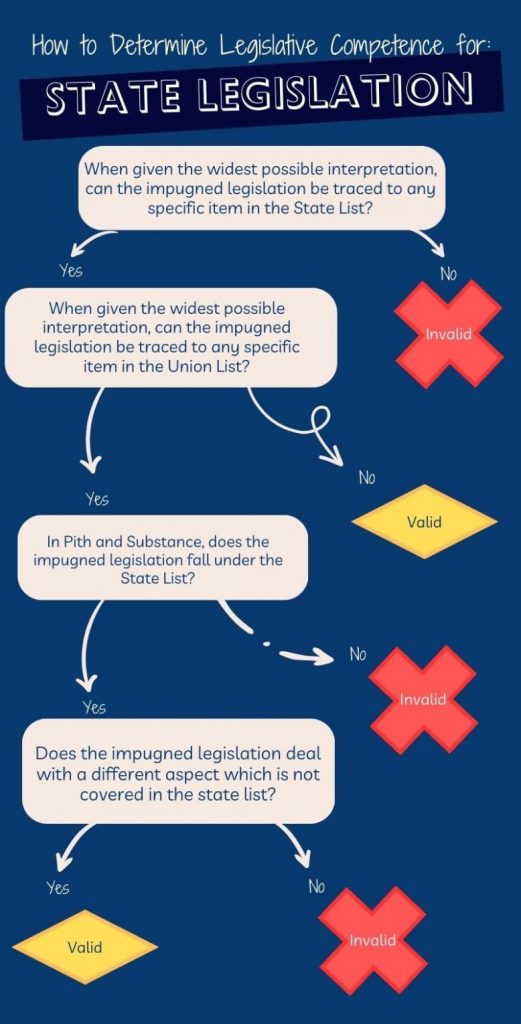

Final overview: Visualizing the adjudication

Over the last four posts, we have delved into the various tests and principles invoked to resolve legislative competence conflicts in the Indian Constitution, along with their history. The existence of several principles and tests can make the process of adjudication fairly complicated. The introduction of the aspects theory along with doubts over its existence adds another layer of complexity to the process. At the potential risk of oversimplification, we have prepared a flowchart that can help us visualize the process of adjudicating the legislative validity of legislations. The flowcharts are as follows:

The way we view these flow charts would depend on how we view the role of the Aspect theory. If we were to consider the Aspects Doctrine as being virtually indistinguishable from the Pith and Substance test, then one could argue against the need for another level of inquiry once the Pith and Substance of a legislation is satisfied. Those who view the Aspects doctrine as a separate test would continue advocating for its application even when the Pith and Substance test gives a conclusive answer. That being said, there is a lot of inconsistency in how the Courts have applied both these tests. These flowcharts have been prepared after surveying the various case laws and principles that the Courts have invoked, and need not necessarily be the way Courts actually adjudicate.

In the next concluding post, we will examine the relevance of the various tests and principles with the advent of the Goods and Services Tax.