A. Introduction

In the previous post, we delved into the ‘pith and substance’ test and various other principles of interpretation that the Indian Courts have invoked while engaging with questions of legislative competence. While Part 1 discussed the pre-Independence developments along with the landmark judgment of C.P. Berar, Part 2 discussed several landmark rulings, such as the Bank of Khulna and H.S. Dhillon. When we examine the ratio of all these rulings, one commonality that all of them share is an engagement with Canadian precedents in order to cull out principles that guide the interpretation of the lists. Each of these judgments not only discuss Canadian constitutional law but its relevance to India as well. Before proceeding further and discussing the infamous ‘Aspects theory’, engaging with Canadian Constitutional Law and examining its relevance in interpreting our Constitution would be worthwhile. This post explores the evolution of interpretive principles in Canadian Constitutional Law and engages with the ‘Aspect theory’ as understood in Canada.

B. Canadian Law

I. Constitutional provisions

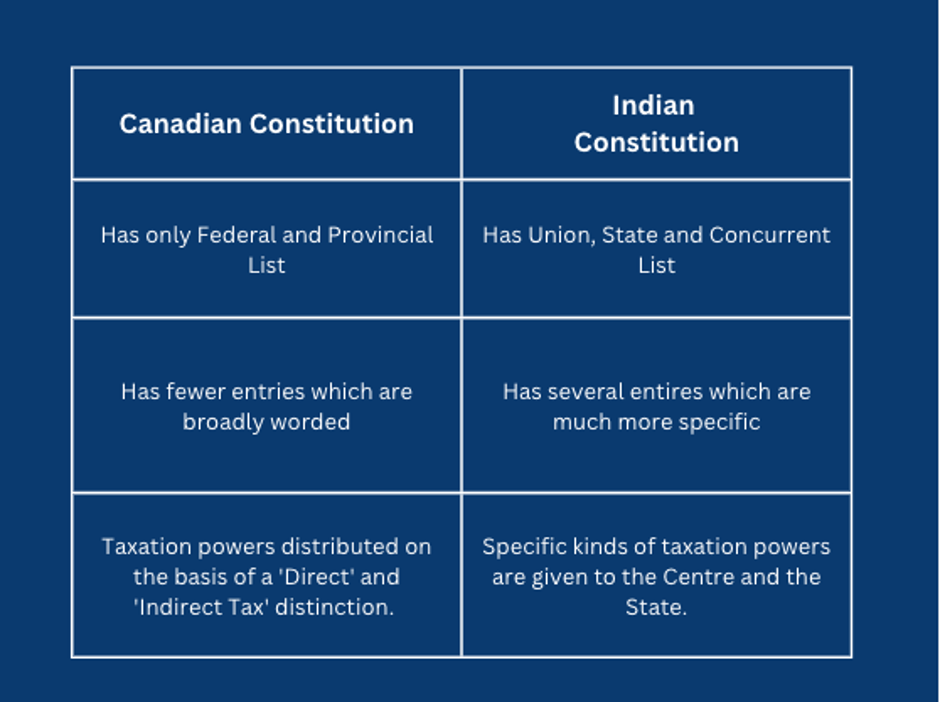

The British North America Act, 1867 (“BNA Act”), which served as the Canadian Constitution until 1982, can be seen as India’s closest constitutional cousin when it comes to distributing legislative fields between the Union and the States in the form of ‘lists’. Unlike the various other federal models at the time, the BNA Act model provided for ‘exclusive’ legislative fields to the Union and Provincial legislatures. Sections 91 and 92 of the BNA Act provided the exclusive legislative heads for the Federal and the Provincial legislatures, respectively. At the time of its repeal in 1982, the Union list contained 29 items, whereas the Provincial list contained 16 items. A quick glance at the Canadian Lists would show that unlike the items in the Indian lists (which are relatively more elaborate and specific), the items in the Canadian list are worded in an open-ended manner. Some such examples include “Regulation of Trade and Commerce” (Federal List, item 2), “Property and Civil Rights in the Province” (Provincial List, item 13), and “Generally all matters of a merely local or private nature in the Province” (Provincial list, item 16).

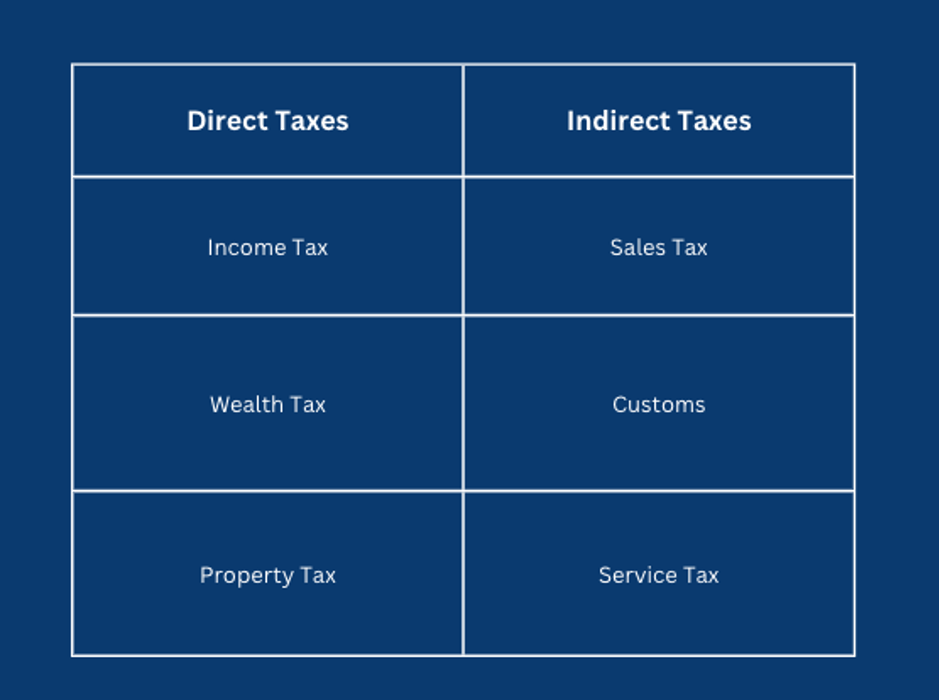

The generality of the terms used in the Canadian lists can also be seen in the taxation-related heads. While the Indian lists enumerate several different types of taxes that the Union and States can levy, the Canadian Constitution merely has two entries. The Federal legislature, under the BNA Act, was provided with the legislative head of “Raising of money by any mode or system of taxation”. In contrast, the Provinces were assigned the head “Direct Taxation within the province in order to the raising of a revenue for provincial purposes”. Commentators have often classified this as meaning Provincial domain over ‘Direct Taxes’ and Federal domain over ‘Indirect Taxes’.

Another point of distinction is the lack of any concurrent list in the Canadian Constitution. Rather than having a list, Section 95 of the BNA Act provides concurrent legislative authority to the Federal and Provincial legislatures on matters pertaining to Agriculture and immigration in the province. Any Provincial legislation in these two areas would be valid so long as it is not repugnant to any Federal legislation. Given the relatively lesser number of entries in the Federal and Provincial lists, coupled with the generality of the terms, conflicts as to the interpretation of the lists were bound to emerge in Canada.

II. Harmonious Interpretation and the Pith and Substance Doctrine

Among the earliest such interpretive conflicts is the case of Citizens Insurance v. Parsons, where the impugned legislation dealt with insurance. It was to be decided whether the same fell under the Federal list (‘Trade and Commerce’) or the Provincial list (‘Property and Civil rights’). Each of these terms are open-ended in nature, and therefore their meaning had to be curtailed to resolve the conflict. For the first time, the Canadian Courts introduced a principle of ‘Mutual Modification’, whereby the meaning of one term may be modified in light of another term with a degree of overlap. This principle of ‘mutual modification’ operated similarly to the principle of harmonious interpretation in the Canadian context, where the Court strives to harmonize entries and read them in light of other entries in the lists. Based on such a harmonious interpretation, insurance was deemed to fall under the legislative head of ‘Property and Civil rights’. This principle of harmonious interpretation was endorsed by the Indian Federal Court in the C.P. Berar case as well.

As stated earlier, the legislative powers of the Federal and Provincial governments under the BNA Act are ‘exclusive’. While the harmonious interpretation of the lists can help modify the interpretation of an item in light of other items, there also remains scope for irreconcilable conflict. In such situations, the Canadian Courts evolved the doctrine of ‘Pith and Substance’ to resolve such interpretational conflicts. Once the ‘dominant purpose’ of a legislation is ascertained, the Court would have to determine which of the items it falls under. Any incidental encroachment onto the other list is acceptable as long as the dominant purpose of the impugned legislation falls in the appropriate list.

The phrase ‘Pith and Substance’ was first used by the Privy Council in the case of Union Colliery Co. of British Columbia Ltd. v. Bryden (“Union Colliery Case”). The impugned legislation involved certain restrictions on people from China working in coalfields. The controversy was whether the same fell under the Federal List (‘Naturalization and Aliens’) or the Provincial List (‘Property and Civil Rights’). Identifying the pith and substance of the legislation as regulation of ‘aliens’, the Court held that the Province had no legislative competence to enact the impugned legislation.

The doctrine of pith and substance is also supported by the doctrine of ‘ancillary powers’. As per this doctrine, if encroaching into the legislative domain of the other list was ‘necessary’ to fulfil the dominant purpose of the impugned legislation, such encroachment would be permissible. Among the earliest invocations of the ancillary effects doctrine is the case of Cushing v. Dupuy, wherein a Federal Legislation on Insolvency Law was upheld notwithstanding the ancillary effect it had on ‘Civil and Property Rights’ in the Provincial List. Interestingly, the doctrine of ancillary powers was, for the longest time, used primarily for the benefit of the Federal Parliament.

III. Pith and Substance as a Common Law doctrine

The Pith and Substance doctrine has been invoked in several other Common Law jurisdictions, especially in the context of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. A commonality shared in the division of legislative authority between the Parliament of the United Kingdom on the one hand and the legislatures of the three aforementioned countries is the idea of a ‘Reserved’/ ‘Excepted’ list. This represents a list of legislative fields over which the British Parliament has exclusive legislative authority. Some such common items across the three different constitutions include International Relations, Armed Forces and general legislations dealing with the Crown. Any legislative head not falling under the Reserved or Excepted list would be deemed to be devolved onto the respective legislatures. Therefore, the only question to be asked regarding the legislative competence is whether the item in question falls within the reserved or excepted list or not.

A landmark case in this regard is the case of Gallagher v. Lynn,[1] where a person was hauled up for selling milk without a license under a Northern Irish law. He contended it by arguing that the law is in respect of trade which does not fall within the Irish parliament’s domain. The House of Lords ruled, however, that the pith and substance of the legislation can be traced to the item ‘Peace, Order and Good Government’ which is among the items devolved to the Irish Parliament. The objective of the impugned legislation is to secure the health of the inhabitants of Northern Ireland and not to regulate trade. Consequently, the impugned legislation was valid. While invoking the Pith and Substance doctrine, the House of Lords extensively relied on Canadian Precedents such as the Union Colliery case and Russell v. Queen.

So far, the ‘Pith and Substance’ doctrine has largely been invoked as a common law principle. Scotland, however, stands out by giving the doctrine a legislative colour. Section 29(3) of the Scotland Act, 1988 states that the Scottish Parliament does not have legislative competence to enact legislations which ‘relate to’ a Reserved List item. Whether or not a legislation ‘relates to’ a reserved item list is, according to Section 29(4),

“to be determined…, by reference to the purpose of the provision, having regard (among other things) to its effect in all the circumstances.”

While the phrase ‘Pith and Substance’ does not appear in the Scotland Act, 1998, the same is referenced in the Explanatory Notes for the Act. The Explanatory notes also cite the case of Gallagher v. Lynn while elaborating on the doctrine as well.

The Pith and Substance doctrine has been invoked by Australian Courts as well. Under the Australian model, there exists only a ‘Federal List’. Any matter that did not fall under the Federal list was automatically deemed to fall under the Provincial Legislature’s domain. The only question therefore is whether the dominant purpose of the law would fall fairly within the head mentioned in the one federal list. Among the earliest invocation of this doctrine is the case of King v. Barger. The impugned legislation was a Federal Excise Law, which provided certain exemptions from the payment of Excise as long as the goods were manufactured under ‘fair and reasonable’ labour conditions. The issue before the Courts was whether the impugned provision was the imposition of an Excise Tax (under the Federal List) or regulation of Labour (deemed to be under the Provincial domain). After surveying several Canadian precedents on Pith and Substance, the Court held the impugned legislation to be invalid for trying to regulating Labour in the garb of imposing a tax. The Australian jurisprudence on legislative competence will be elaborated on more in the segment on the Double Aspect theory.

IV. Pith and substance in the context of Taxation entries

Interestingly, while the Pith and Substance test was used extensively in Canadian Constitutional Law, its application is fairly limited in interpreting the taxation-related entries in the lists. As stated earlier, the Canadian distribution of fiscal powers can be broadly categorized in the form of Direct and Indirect Taxation, with the former going to the Provinces and the latter to the Federal Government. The Federal Court in C.P. and Berar surveys several such cases which lay down the foundational principles for distinguishing direct and indirect taxation. While a direct tax is understood as a tax directly on the person intended to pay it, indirect tax refers to those taxes whose burden can be shifted onto other persons. Some examples can be seen below:

Given the stark difference between the Indian and Canadian approaches towards Taxation-related entries, the relevance of Canadian precedents as aids of interpretation has also been questioned by the Indian Supreme Court. The differing opinions of C.J. Sikri and J. Shehlat in the H.S. Dhillon case are illustrative of the different approaches towards Canadian precedents for interpreting the lists. In his opinion, C.J. Sikri placed considerable reliance on Canadian precedents dealing with residuary powers. He noted that the Canadian test with respect to the Union’s residuary power was merely to check whether the impugned legislation fell under any of the entries in the Province’s list. If it did not, then the Federal Government had legislative competence, and no further questions had to be asked.

On the other hand, J. Shehlat questioned the efficacy of using the Canadian model as an appropriate analogy. In his opinion, there was no similarity between the distributive system in the Canadian and Indian Constitutions. The Canadian distribution model, he notes, is “interlacing” and not disjunctive. As a result, entries across both lists are interlaced with one another. In the Indian Constitution, however, the entries are disjunctive. Rather than interlacing the entries in the Indian Constitution, the lists provide for independent spheres of legislation. While rejecting reliance on Canadian precedents for interpreting the Union’s residuary powers, J. Shehlat also cautions against the dangers of blindly applying Canadian precedents while interpreting the Indian Constitution and its lists.

V. Aspect Theory

Notwithstanding the pith and substance doctrine and the various other interpretive principles, the generality and vagueness of the terms used in the BNA Act can result in scenarios where it becomes impossible to pinpoint just one source of legislative power for a legislation. A classic example in this regard would be a legislation dealing with ‘Rash Driving’. While ‘Public Order’ falls under the Federal list, ‘Property and Civil Rights’ falls under the State list. Any legislation dealing with the civil consequences of Rash Driving could equally fall under either head, and the aforementioned principles do not help the interpreter beyond a point. In order to fully give effect to the principle of harmonious construction, the Canadian Courts began emphasizing the need for ‘cooperation’ between the Federal and Provincial levels. Such cooperation, the Courts noted, often required tolerating a high degree of overlap between the Federal and Provincial lists. This principle formed the bedrock for the so-called ‘Aspects Doctrine’ in Canadian Constitutional Law.

The double aspect theory envisions a scenario where an impugned legislation may fall under the Federal list in one aspect and the provincial list in another aspect. The origins of this case can be traced back to 1883 with the Privy Council’s decision in Hodge v. The Queen, where the Court held that a law prohibiting certain activities in Pubs and Taverns fell under the Federal or Provincial List. While the former contained ‘Regulation of Trade and Commerce’, the latter contained ‘Public order, decency and Morality’. Upholding the Provincial Legislation, the Court laid down the principle that those subjects which, in one aspect and for one purpose, fall within the Federal List may, in another aspect and for another purpose, fall within the Provincial List. Applying the same to the rash driving illustration, the impugned legislation would fall under the ambit of the Provinces to the extent that it provided for the civil consequences of rash driving. At the same time, the Federal Government would continue to have the power to prescribe criminal penalties for the same and mandate safeguards in the traffic rules.

The Australian courts have also recognized this double aspect of law. In the case of Actors and Announces Equity Association v. Fontana Films, the impugned federal legislation prohibited certain types of Trade Union activities which interfered with supplies to a ‘Corporation’. The courts had to determine whether the impugned legislation can trace its legislative source to the item ‘Corporations’ as falling under the Federal list. The Court held as follows:

10. To recognize that a law may possess a number of quite disparate characters is, then, to accept reality. Few laws will involve only one element. Even the simplest form of law will commonly contain two elements when it forbids, regulates or mandates particular conduct on the part of a particular class of person. The conduct and the class will form distinct elements and if each happens to bear a relationship to different grants of legislative power the law may often be equally appropriately described by reference to either.

As per this understanding, the ‘Class of Persons’ who are being regulated and the ‘Category of Activities’ that is being regulated would both count as different yet equally important aspects of law. As an illustration, we can consider a law placing restrictions on industries from polluting to be a law on ‘Industries’ as well as ‘Pollution’. This understanding of the duality of law enabled the Court to uphold the validity of the impugned legislation by tracing one of its legislative sources to the Federal List.

It is imperative to note that the aspects doctrine, as per the Canadian Supreme Court, is applied ‘in the course of the pith and substance analysis’. Therefore, according to the Canadian Supreme Court, the same cannot be seen as an entirely separate test. The Canadian Supreme Court has also sounded a word of caution regarding the aspect theory (See Bell Canada v. Quebec). The structure of the Canadian lists continues to be that of providing the Federal and Provincial levels of government ‘exclusive’ legislative powers. However, unbridled expansion of the aspect theory could theoretically dilute this exclusive nature by making every field of legislation a concurrent one. As a result, the Canadian Supreme Court has held that the aspect theory can be resorted to only when the multiplicity of aspects is ‘real’ and not merely illusory. Like the pith and substance doctrine, the aspects doctrine has not been applied to resolve taxation-related disputes in Canada.

In the next article, we will explore how the Indian Courts have invoked the aspect theory when faced with issues of legislative competence.

C. Bibliography

- Tony Blackshield, Working The Metaphor: The Contrasting Use Of ‘Pith And Substance’ In Indian And Australian Law, Journal of the Indian Law Institute, vol. 50, no. 4, 2008, pp. 518–68.

- Eugene Brouillet and Bruce Ryder, Key Doctrines in Canadian Legal Federalism, The Oxford Handbook of the Canadian Constitution 415-432 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- David Torrance, Reserved matters in the United Kingdom, Research Briefing, House of Commons Library.