Akarshi Narain is a fourth-year law student at NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad, with a keen interest in constitutional law, fiscal federalism, and policy analysis.

“GST exemplifies cooperative federalism in India, empowering states”

– Nirmala Sitharaman

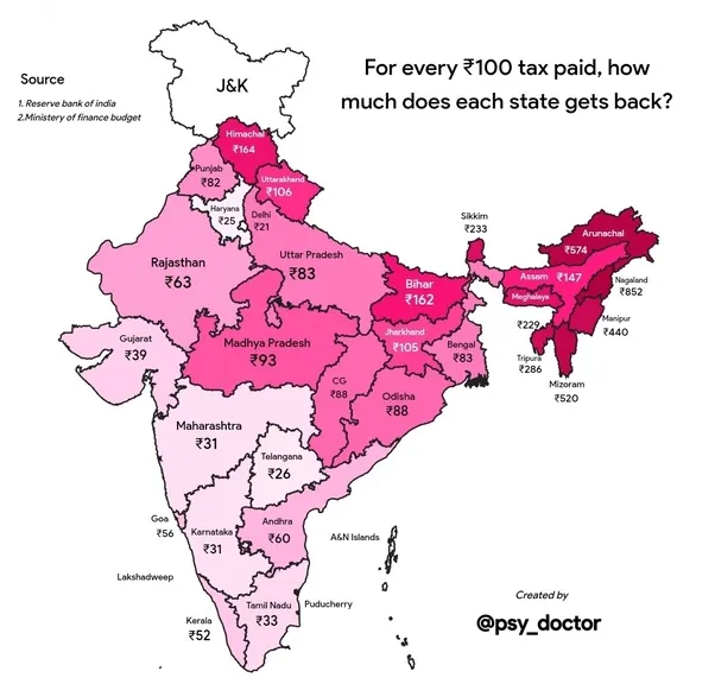

The implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India has ignited a contentious debate on fiscal federalism and equitable resource distribution. While the current system aims to promote balanced regional development, it has led to significant grievances, particularly among southern states. Recently, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka have been at the forefront of protests against what they perceive as flawed GST implementation. These states, despite being major contributors to the GST pool and displaying fiscal responsibility, receive disproportionately small returns through devolution. Conversely, several northern states, often characterised by lower growth and employment rates, receive a disproportionately larger share of federal taxes. Recent statistics from the Reserve Bank of India (2021-23) illustrate this disparity. On average, for every Rs 65 collected by states as CGST, the Centre should provide Rs 35. However, the redistribution varies significantly: Kerala receives Rs 21, Uttar Pradesh Rs 46, and Bihar Rs 70 for every Rs 100 collected by the Centre.

INTRODUCTION

This disparity has fuelled a sentiment of discrimination among southern states and hampered their ability to finance local welfare programs. Notably, this issue has come to the forefront after seven years of GST implementation, with the cumulative experience revealing deeper structural imbalances. The initial optimism around GST as a unifying fiscal policy has now given way to debates over its long-term viability in ensuring fairness across states. Before we delve into this debate, it is essential to acknowledge that this issue is not just driven by fiscal factors but is also strongly influenced by broader political dynamics.

UNDERSTANDING GST DEVOLUTION

To assess the fairness of the current devolution system, it is crucial to understand its mechanics. The Finance Commission formulates the tax devolution formula, which is periodically reviewed. While states retain all state GST (SGST), the central GST (CGST) is collected by the Centre, with 41% redistributed among states (vertical devolution). The issue lies in the fact that this distribution is not uniform; population weighs in as a major indicator in the allocation formula (horizontal devolution).

The recent Finance Commission recommendations have only added fuel to the fire. Until the 13th Finance Commission, the 1971 census served as the foundation for the distribution of central funds. Thus, in theory, the states that have maintained population control since 1971 should receive a marginally larger share of the total allotment. The 14th Finance Commission adopted partial use of Census 2011 data in the distribution formula. The 15th Finance Commission switched to full use of the Census 2011 data set which they argued was more representative and captured the newer population trend across states. However, this led to a paradoxical situation where southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, who have successfully implemented population control measures, were being penalised for the same via lower fiscal devolution.

Notably, to navigate the challenge of using the 2011 population metric, the 15th Finance Commission introduced the ‘demographic performance’ parameter, intended to serve as a proxy for population control. This was meant to reward states that had successfully managed population growth since the 1970s. However, flaws in the methodology used to assess demographic performance led to some unexpected and counterproductive outcomes. For instance, states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, despite having higher population growth rates, ranked surprisingly high on this metric, undermining its original intent.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The roots of this controversy trace back to the foundations of India’s fiscal structure. Interestingly, the recommendations of the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946 proffered that the states should enjoy significant fiscal autonomy and the Union should have extremely limited restricting power. However, political agendas of the time prevailed and India chose a fiscal system strongly skewed towards the Centre.

The GST regime introduced in 2017 further tilted the scales towards the Centre. Pre-GST, states possessed fiscal sovereignty regarding value-added tax rates, which could be tweaked as per the State’s needs. GST took away this limited autonomy as well, inducing states to be increasingly dependent on federal transfers. Moreover, southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, having completed major public works decades ago, often miss out on centrally sponsored schemes aimed at such developments, further limiting their access to central funds. Therefore, multiple policy decisions have negatively impacted southern states and destroyed their fiscal autonomy in the federal structure.

DECONSTRUCTING THE FISCAL DISPARITY

Prima facie, it appears that southern states have got the shorter end of the stick. However, a comprehensive analysis reveals a more nuanced picture.

Firstly, contrary to popular perception, the divide is not strictly between the South and North. Several northern states, including Haryana and Delhi, contribute substantially to the Centre while receiving a smaller share in return. This pattern challenges the simplistic narrative of southern states being uniquely disadvantaged. The question that must be asked then is, why do some states get more from the Centre than others? The answer lies in the fact that India follows a ‘Progressive tax model’. Under this model, relatively wealthier states contribute more to support the development of economically weaker regions, aiming to reduce overall regional disparity. This approach is not unique to India but is also employed in other federal systems, such as the United States and the European Union.

Secondly, there are several indirect benefits enjoyed by southern states due to contributions by other states. For example, the raw material for Chennai’s famous automobile manufacturing industry comes from eastern states like Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh. A majority of states such as Telangana and Andhra Pradesh depend on coal for electricity generation and a major part of this is supplied by eastern states. Along with access to raw material, they also enjoy benefit from access to cheap labour and larger markets.

THE WAY FORWARD

These factors illustrate that the relationship between states is more symbiotic than it might appear at first glance. At the same time, the southern states’ resentment about being punished for successfully controlling their population merits serious consideration. Given that population management is one of India’s biggest problems, such a treatment might disincentive population control measures, which India can ill-afford. Consequently, the author identifies certain problem areas that require expert deliberation to actually achieve ‘cooperative federalism.’

Firstly, I argue for a critical reassessment of the indicators informing the distribution formula. Many experts argue that population, as a metric, fails to accurately capture a state’s true fiscal needs and developmental requirements. Historical trends in Finance Commission recommendations support this view. Till the 7th Finance Commission, 80-90% weightage was given to the population in deciding distribution of income tax. The 8th Finance Commission saw a substantial decline in this, to 22.5%, while the 11th Finance Commission saw it drop as low as 10%. However, the 12th Finance Commission’s gradual ascent to 25% and beyond has been regressive. The demographic numbers of an area could very easily fail to accurately reflect its developmental needs. Striking a balance between more granular criteria such as development levels, fiscal discipline, and fiscal disabilities such as per capita income distance seems more sensible. This should be complemented with updating the tax devolution criteria to reflect demographic changes. For instance, considering the demographic transition to an increasing elderly population in India, we could introduce a criterion based on the elderly-to-working-age population ratio, where states with a higher number of dependents would require greater resources.

Secondly, if the revised indicators contain a weaker population metric, the ‘punishment for success’ argument will naturally lose some steam given its population basis. However, it may not fully alleviate the resentment. To address this, a system of monetary incentives for states that have demonstrably reduced their population through concerted efforts, complementing the revised formula, can be explored. This approach offers several benefits- it acknowledges and rewards past successes in population control, provides a counterbalance to the perceived punishment for success, creates a positive incentive for other states to prioritise population management, and discourages the practice of relying on larger populations to secure greater tax revenues.

Thirdly, and most importantly, before any solutions are proposed, it is essential to have an accurate and updated understanding of the problem. This hinges on obtaining reliable and up-to-date demographic data, which is currently missing due to the delay in conducting the long-pending national census. Without this crucial data, any reassessment of the distribution formula or proposed reforms would be based on outdated figures that fail to capture the present-day realities. A fresh census would not only provide a clearer picture of population dynamics but also offer insights into shifts in regional development, including the significant migration to Tier-2 and 3 cities, fiscal needs, and disparities between states. This is particularly important given the evolving economic landscape, where outdated data could lead to misguided policies or the reinforcement of existing inequities. Thus, it is imperative for the 16th Finance Commission to underline the importance of conducting the nationwide census and recommending the same to the government, emphasizing the importance of accurate and current demographic figures for fair and equitable fiscal policy.

Furthermore, updated census data would allow for a more informed debate between the Centre and the southern states. Both sides could ground their arguments in present realities, strengthening the legitimacy of claims regarding fiscal fairness and developmental needs. For instance, the southern states could more effectively argue for reduced reliance on population metrics, while the Centre could better assess which regions genuinely require greater fiscal support based on current indicators. In essence, the census would serve as the foundation for any meaningful reform, ensuring that the solutions proposed are equitable, data-driven, and reflective of India’s contemporary challenges.

CONCLUSION

The GST devolution debate underscores the challenges of maintaining a balance between regional aspirations and national development goals in a diverse federal system. As India continues to evolve economically and socially, it is imperative that its fiscal policies adapt to ensure both equitable growth and national cohesion.

Moving forward, policymakers must strive to create a system that not only addresses the valid concerns of high contributor states but also maintains the spirit of cooperative federalism essential for India’s progress. This will require ongoing dialogue, data-driven analysis, and a willingness to consider innovative solutions that can accommodate the diverse needs of all states while advancing the nation’s overall development.

rtp slot