This piece explores how, despite international acknowledgement of tax regime inequality, little action has been taken to mitigate the dominance of capital-rich nations. Current tax systems exacerbate income disparities, especially harming lower-income countries. Proposed solutions like the BEPS Project lack inclusivity and fail to address the needs of the Third World. Regional collaborations offer potential, yet must prioritise equitable redistribution over capital accumulation for true effectiveness. This series was written by Samvedh, Kartheek, Dhanush, and Aditya from the CTL team.

Introduction

While the core of tax treaties and the dependence on pre-existing models dilute national sovereignty, a larger issue arises from the disproportionate impact that the international tax regime has on the Third World. Tax treaties, and Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAAs) in particular, continue the colonial practice of vesting the right to the revenue of developing countries in developed countries. DTAAs, ironically, are consent-based mechanisms where lower-income countries voluntarily become parties to them.

Concerns have been raised over the operation of such DTAAs and the legitimacy of the international tax regime when lower-income countries fail to be a part of the dialogue that affects how they organise their tax systems. This article will delve into how DTAAs and bilateral tax treaties negatively impact lower-income countries with references to the different taxation models (by the OECD and the UN). It will also analyse how the tax regime lacks legitimacy in its application to developing countries due to the existing hegemony within multilateral institutions and academic spaces responsible for knowledge creation on taxation standards.

The Imperial Nature of DTAAs

The traditional literature on the side of both policy and academia suggests that tax treaties are a mechanism that allows for a greater inflow of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to lower-income countries, even if they are at the cost of tax revenue. Scholars argue that they are a method by which developing countries compete for investment, thereby being an important tool to attract investors.[1] However, empirical evidence proves otherwise; the primary source of income for many developing countries arises from corporate tax revenue.[2] The IMF estimates that African countries experience a 5% reduction in corporate tax revenue with each additional tax treaty they sign.[3]

The logic of DTAAs assumes that the flows of investment and people between parties to a treaty are equal; in such a situation, taxpayers would be incentivised to move between countries when there is a change in the balance of taxing rights.[4] The distribution of taxing rights would remain the same since each country would be both a resident and a source country with regard to different investors, and the restrictions on taxing rights would lead to a similar proportion of gain and loss for each country. However, when the distribution of capital stocks between two countries is unequal, the distribution of revenue will also be highly skewed. Capital importers would lose a considerable amount of revenue as compared to capital exporters when entering into treaties that sacrifice their right to taxation.

DTAAs are premised on the need to help taxpayers avoid being taxed twice, by the home country and the residence country. However, these treaties merely shift the burden of non-taxation from the home country to the residence country. In exchange for the restrictions on the residence countries, home countries agree to limit their right to tax their own residents; these restrictions are unnecessary since, even in the absence of a treaty, such countries provide credit against tax paid abroad or even completely exempt foreign profits from tax.[5]

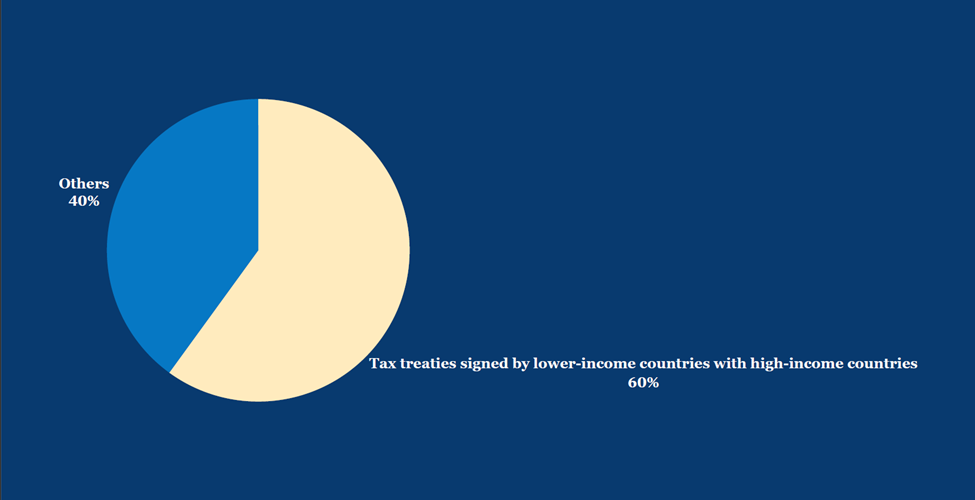

The empirical evidence surrounding the inflow of investment into developing countries is contradictory at best. Some studies since 2009 have shown a minimal positive correlation between tax treaties and investment, whereas many others have found none.[6] Challenges, however, remain in the quality and coverage of data in the case of lower-income countries.[7] More importantly, the available economic and legal evidence does not necessarily suggest that the benefits of investment inflow completely outweigh the costs of foregone revenue. Around 60% of the tax treaties signed by lower-income countries are with high-income countries; only 1% of tax treaties are between two low-income countries.[8] The logical inference is that the flow of trade and investment is mostly unilateral from economically-developed countries.

Sergio Rocha identifies another form of imperialism within the international tax regime. The rhetoric of tax avoidance is directed against taxpayers (mostly large Multinational Entities), whose aggressive tax planning leads to a loss of revenue for numerous countries. However, such profit shifting and base erosion would not be possible without the preferential tax rules offered by countries, which include low or even no taxes to these entities and lenient profit measurement systems.[9]

He also provides the example of ‘permanent establishment’ within the OECD and UN Model Conventions. The idea that an entity cannot undertake business to a significant extent in another jurisdiction without the presence of a permanent establishment may be reasonable and valid but cannot be posited as a fundamental principle of international taxation law, as suggested by numerous scholars. The intention, therefore, remains to eliminate other valid and coherent models of taxation, such as earnings within a source country. Similarly, allowing passive income to be taxable only in the hands of the residence state throttles the tax revenue of developing countries; it has nonetheless transformed into a standard of international tax.[10]

The introduction to the OECD Model Tax Convention describes its main purpose as “to clarify, standardise, and confirm the fiscal situation of taxpayers who are engaged in commercial, industrial, financial, or any other activities in other countries through the application by all countries of common solutions to identical cases of double taxation”.[11] By their presence in these Model Conventions, these standards of international tax become canonised, formalised to the extent that an entire network of treaties becomes based on them.

While the OECD model is a consistent target of criticism, the UN model arose to provide a better alternative to developing countries. However, critics have noted its use of the OECD model as its basis and also the continuing presence of a permanent establishment requirement, reducing the capacity to allow taxation within a host country.[12] The UN Model was proposed to establish fairer rules for a more equitable distribution of tax revenue between developed and developing countries. Nonetheless, the negotiation stage witnessed some disagreement between representatives of the two global communities, with developed countries arguing that the OECD Model should remain the basis for the UN Model as well, which ultimately prevailed. The UN Model is therefore not based on the source principle, but instead on the domicile principle, therefore allowing for taxation in the country of origin in many instances.[13]

Capital-exporting companies (usually high-income developed countries) have a greater incentive to enter into double-taxation avoidance treaties since the cost of relieving double-taxation is transferred to the capital-importing state, even though such taxation can be relieved unilaterally. Taxation is limited primarily in the capital-importing state, whereas the home state offers to bear the cost of relieving remaining double-taxation by offering credits for tax paid abroad or the exemption of profits in the treaty partner’s jurisdiction.[14]

BEPS: A Way Forward?

The OECD/G-20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan has been proposed as a cooperative alternative to the inequal model taxation frameworks that currently exist. However, criticism has been targeted for its pursuit to continue cooperation within a competitive framework. BEPS targets ‘virtual’ tax competition wherein tax policies attract profits from economic activities in other places, whereas ‘real’ tax competition, that attracts investments, is left untouched.[15]

The concept of ‘value creation’ figures significantly within the BEPS project, which assumes that income shall be taxed where economic activities take place and value is created. Conflicting accounts of what may constitute ‘value’ challenges this assumption; value may be generated through the process of labour or where the wants and needs of consumers first arise. Transnational supply chains and distribution further complicate the taxation of a concept as ambiguous as ‘value’.[16]

Further concerns remain over the preferential nature of the BEPS project towards developed countries. Changes have been proposed to the Arms’ Length Principle, according to which two related parties must transact for the same price that unrelated parties would in the same transaction; within the BEPS Action Plan, taxation would be shifted to capital-exporting countries. For digital economic activities, it proposes expanding the taxing rights to jurisdictions with greater users, countries that have greater purchasing power.[17] This proposal would cover only a small amount of developing countries, once again privileging the Global North.

Action 14 of the BEPS Project proposes that countries adopt mandatory binding arbitration in their treaties to resolve any contentions surrounding the application of tax treaties.[18] It is to be noted that numerous countries use the UN Model Convention as the basis for their tax treaties, such as India and Brazil. The use of binding arbitration would expose negotiated treaties to the theoretical biases of developed countries due to the persisting influence of OECD standards, which may also lead to the overriding of national tax policy. This concern is especially relevant if the threshold standard is the OECD’s Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.[19]

The BEPS Project also actively seeks to combat treaty shopping as part of its actions against treaty abuse. While treaty shopping remains a serious problem, it could be conceded that it may in fact help in attracting investment towards developing countries. Citing the Supreme Court of India’s decision in the Azadi Bachao Andolan case, scholars argue that some developing countries may actually stand to benefit from creative use of treaties by Multinational Entities when it is under the garb of tax planning.[20] The argument herein is not that treaty shopping must be universally allowed, but that developing countries must keep into consideration the benefits that may be sacrificed through an uncritical adherence to the BEPS Multilateral Convention.

The Tax Regime and Knowledge Monopolies

Treaties obtain their standards from concepts that are concretised over decades, often much before developing countries have even obtained independence. The bilateral tax treaty between Austro-Hungary and Prussia introduced the concept of ‘Permanent Establishment’ (PE) in 1889. Certain countries, such as Uganda, do not even have such a concept within their domestic framework; accepting PE through a treaty will therefore be restrictive regardless of how broad its definition is relative to their domestic taxation laws.[21] International tax rules, including those in DTAAs, are therefore built around assumptions propagated by developed countries.

Transnational corporate entities have a significant interest in reduced tax rates and the lack of any countervailing force to this lobby means that states’ preferences are ordered around increasing trade and investment by eliminating double-taxation. Rocha further argues that political actors responsible for realising tax treaties have their preferences guided by international tax specialists; the latter also hold a veto through the complex network of terminologies created by them.[22] Most of these specialists operate among experts from OECD countries, whose rhetoric of ‘economic efficiency’ rather than redistributing international wealth guides international taxation.

At a preliminary level, numerous lower-income countries lack the bureaucratic capacity to enter into efficient treaty negotiations. Treaties entered into as early as 1974, such as in Zambia, reflect the weaker bargaining position of developing countries.[23] Policymakers in African countries, for example, are not equipped with the knowledge required to manoeuvre the complex nature of international taxation. Empirical evidence in many countries demonstrates how numerous lower-income countries have been a part of disadvantageous tax treaties due to the lack of clear negotiation policies.[24] Even when such tax negotiations are entered into, the opportunity cost of diverting scarce resources tends to make these endeavours expensive for lower-income countries.

The theoretical gap between developing and developed countries also exist in the kind of academic output produced in the former, where literature on taxation is produced by practitioners rather than full-time academics. Tax literature is, therefore, almost exclusively a product of developed countries, whose hegemony in international institutions allows a synergy these academics and the development of tax “standards”.[25]

Legitimacy Deficits within the International Tax Regime

Countries within the Global North obtained an advantage beginning from the 1920s in the League of Nations, deciding on their own terms of cooperation that were solidified before developing countries had a chance to join. The OECD’s institutional standards were based on the work completed within the League of Nations, benefitting its capital-rich neighbours. Gaining acceptance within the international community requires newly independent countries to conform to those treaties and rules already in place, putting lower-income countries at an immediate disadvantage.[26]

The OECD is primarily responsible for tax cooperation in the 21st century, to the extent of influencing the taxing decisions of even non-member countries. While the institution may retain its mandate to create binding policies for its members, it aims to remain a “global standard setting body”. Its claim is indented by the fact that the G20, responsible for the BEPS Project, is constituted of advanced and emerging entities that represent 90% of global GDP, 80% of world trade, and two-thirds of the world’s population. Its economic weight is said to add to its legitimacy to shape the rules of the international financial system; however, it lacks any meaningful representation from Asia and Africa, and no participation from low-income and small countries. Even within those countries represented, nations within the EU fear that the decisions on behalf of the union will represent only those larger European countries.[27] The fear from the Global South is, therefore, more than warranted.

The governance structure of the OECD has come under criticism due to the lack of any mechanisms for electoral representation. The G20 further lacks legal personality or any treaty or charter defining its capacities as an organisation. Deliberations within the G20 are private and are host to numerous accountability and transparency issues. In addition, both the OECD and G20 lack the authority to create binding tax rules and sanctions in case of non-compliance. Both institutions also lack active participation and deliberative procedures from citizens and civil society, further stratifying their unequal nature. Concerns also exist over the possibility of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other interest groups influencing the policies of the OECD.[28]

The lack of such governance standards leaves these organisations vulnerable to co-option by strong economic and political stakeholders, a phenomenon that exists strongly in the current regime. Even if increased participation were to be achieved, scholars such as Ivan Ozai point out that tax standards and concepts have been entrenched in a way that makes participation less meaningful, a phenomenon he terms ‘structural legitimacy deficit’. There are larger structural inequities that make the power differential within these organisations difficult to overcome.[29]

The BEPS Project, in specific, was launched while keeping in concern the participatory defects that may arise through the non-inclusion of developing countries. Eight non-OECD countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa) were thus invited as ‘Associates’ to have an equal role in the drafting of the Action Plans, whereas some non-G20 non-OECD countries were called on as ‘Invitees’. However, Associates could only be involved in the BEPS process after the agenda for the BEPS initiative had been established, and Invitees had only a consultative role. Furthermore, more than two-thirds of UN member nations were not involved in any capacity with the BEPS Project.

Some scholars argue that the inclusive activities of the OECD in recent times have less to do with participation but instead enhance the image of the institution as one driven by inclusivity. The participation of lower-income countries has been limited mostly to the stage of implementation and endorsement, whereas they fail to be included in the actual articulation of these standards.

In fact, many of these standards follow the ideological goals of the Global North. As highlighted previously, tax competition prevents countries from orienting their tax systems to promote normative redistributive goals, instead prioritising economic liberalism and investment. Tax competition allows the rich to relocate their income, thereby preventing vertical equity. Shifting the tax burden from capital to labour also prevents the horizontal redistribution of wealth. Additionally, the main issue in tax competition is not the difficulties in attracting investment but instead the arbitrary relocation of paper profits by MNEs.[30]

At a moral level, the interference of the global economic system in the functioning of states requires that the rules made by supranational nations involve equity and coordination between those affected. The untrammelled growth of economic globalisation has led to greater inequalities between nations, with Sub-Saharan Africa prepared to witness the largest concentration of extreme poverty.[31] Thus, the allocation of tax revenue in a manner that favours developed countries leaves developing countries absolutely worse off but also leaves a significantly negative distributive impact.

Questions have been raised as to whether the UN’s Model Taxation Framework produces a relatively more legitimate system. However, even the UN Model is not a product of ratification by member states, instead being drafted wholly by tax experts within the organisations. Much of the issues within the OECD riddle the UN as well, with similar criticism being brought against its monopoly by a few sovereign powers and the lack of accountability and transparency within the organisation.[32]

The recent resolution adopted by the General Assembly on “Promotion of inclusive and effective tax cooperation at the United Nations” reaffirms previous commitments to increase international tax cooperation.[33] The Secretary-General will prepare a report analysing the current legal framework pertaining to international tax cooperation and what future steps would best further the goals enshrined in the resolution, with Member States and other stakeholders such as civil society actors being able to consult in the process. Whether the final action will be one driven by inclusivity and the voices of developing countries is yet to be seen.

Conclusion

While the international community seemingly recognises the unequal nature of the tax regime, little has been done to dilute the stronghold on institutions and standards by capital-rich countries. As it stands, the current tax regime leads to an inequitable distribution of tax revenue and increases distributive inequalities, leaving lower-income countries worse off. Numerous alternatives have been proposed, such as the BEPS Project and the latest UN Resolution on inclusive tax cooperation. However, analyses of these alternatives demonstrate that even they lack the requirements necessary to ensure a more equitable distribution and more importantly, omit the crucial condition of ensuring participation of the Third World.

Regional arrangements may allow developing and lower-income countries to consolidate their influence against those of the bigger powers. There may nonetheless remain a power differential within these regimes as well. It is important that any efforts in this regard break away from the ideological forces that prioritise growth and the accumulation of capital and instead take into account the wider normative requirements of redistribution and cooperation.

[1] Fabian Barthel and Eric Neumayer, Competing for Scarce Foreign Capital: Spatial Dependence in the Diffusion of Double Taxation Treaties, 56 International Studies Quarterly, Dec. 2012.

[2] UNCTAD, International Tax and Investment Policy Coherence, in World Investment Report, 2015 (Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2015), 175–218, http://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters /wir2015ch5en.pdf.

[3] IMF, Countering Tax Avoidance in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Mining Sector, IMF Blog (Nov. 2021).

[4] Martin Hearson, Imposing Standards: The North-South Dimension to Global Tax Politics 11 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

[5] Org. of Economic Cooperation and Development, Tax Sparing: A Reconsideration (OECD Publishing, 1998).

[6] Karl P. Sauvant and Lisa E. Sachs, eds., The Effect of Treaties on Foreign Direct Investment

(Oxford University Press, 2009).

[7] id.

[8] Sébastien Leduc and Geerten Michielse, Are Tax Treaties Worth It for Developing Economies?, in Corporate Income Taxes under Pressure: Why Reform Is Needed and How It Could Be Designed (Ruud A. de Mooij et. al, 2021).

[9] Sergio Andre Rocha, The Other Side of BEPS: “Imperial Taxation” and “International Tax Imperialism”, in Tax Sovereignty in the BEPS Era (Sergio Rocha and Allison Christians, 2017).

[10] id.

[11] OECD, Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (Paris: OECD Publishing,

2014), 7.

[12] supra note 4 at 189.

[13] F. N. Dornelles, The UN Model to Eliminate Double Taxation of Income and Developing Countries in Tax Principles in Brazilian and Comparative Law 201 (Tavolaro et. al, 1988).

[14] PWC, Evolution of Territorial Tax Systems in the OECD (Washington, DC: Prepared

for the Technology CEO Council, 2013).

[15] Laurens van Apeldoorn, BEPS, tax sovereignty and global justice, 14 Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy 478-499 (2018).

[16] Patrik Emblad, Power and sovereignty. How economic-ideological forces constrain sovereignty to tax, 4 Nordic Journal on Law and Society 1-26 (2021).

[17] Org. of Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, Public Consultation Document: Addressing the Tax Challenges of the Digitalisation of the Economy (2019).

[18] Org. of Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], Making Dispute Resolution Mechanisms More Effective, at 41 (2015).

[19] supra note 9.

[20] Paulo Ayres Barreto and Caio Augusto, The Prevention of Tax Treaty Abuse in the BEPS Action

6: A Brazilian Perspective, 43(12) Intertax 828 (2015).

[21] Martin Hearson and Julia Kangave, A Review of Uganda’s Tax Treaties and Recommendations for Action (Int’l Centre for Tax and Dev., 2016).

[22] supra note 9.

[23] Charles R. Irish, International Double Taxation Agreements and Income Taxation at Source, 23 (2) The Int’l & Comparative Law Quarterly 300-301 (1974).

[24] id at 309.

[25] supra note 9.

[26] Philipp Genschel and Thomas Rixen, Settling and Unsettling the Transnational Legal Order of International

Taxation, in Transnational Legal Orders, ed. T. C. Halliday and G. Shaffer, Cambridge

Studies in Law and Society 154-86 (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[27] J. Vestergaard, ‘The G20 and Beyond: Towards Effective Global Economic Governance’, DIIS Report2011:04.

[28] Sissie Fung, The Questionable Legitimacy of the OECD/G20 BEPS Project, 2 Erasmus Law Review (Dec. 2017).

[29] Ivan Ozai, Two Accounts of International Tax Justice, 33 (2) Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence (Aug. 2022).

[30] Thomas Rixen, Tax Competition and Inequality: The Case for Global Tax Governance, 17:4 Global Governance (2011).

[31] Joe Hasell et. al, Poverty, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/poverty.

[32] J.E. Alvarez, ‘Introducing the Themes’, (Introduction to Symposium on ‘Democratic Theory and International Law’), 38 Victoria University of Wellington Law Review 159 (2007).

[33] G.A. Res. 77/244, Promotion of Inclusive and Effective Tax Cooperation at the United Nations (Jan. 9, 2023).

bento4d situs toto situs toto rtp slot situs hk bento4d bento4d situs toto toto togel toto slot toto slot link slot gacor slot thailand slot gacor rtp slot